|

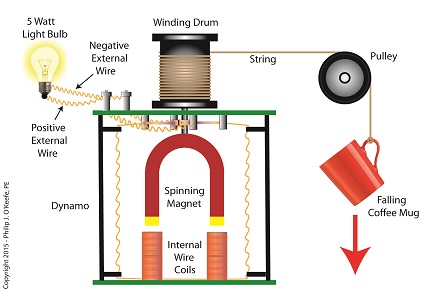

When acting as an engineering expert I’m often called upon to investigate incidents where energy converts from one form to another, a phenomenon that James Prescott Joule observed when he built his apparatus and performed his experiments with electricity. Today we’ll apply Joule’s findings to our own experiment with a coffee mug when we convert its kinetic energy into electrical energy and see how the units used to express that energy also change. We had previously calculated the kinetic energy contained within our falling coffee mug to be 4.9 kg • meter2/second2, also known as 4.9 Joules of energy, by using de Coriolis’ Kinetic Energy Formula. Now most of us don’t speak in terms of Joules of energy, but that’s easily addressed. As we learned in a previous blog on The Law of Conservation of Energy, all forms of energy are equivalent and energy can be converted from one form to another, and when it does, the unit of energy used to express it also changes. Let’s say we want to put our mug’s 4.9 Joules of kinetic energy to good use and power an electric light bulb. First we must first find a way of converting the mug’s kinetic energy into electrical energy. To do so, we’ll combine Joule’s apparatus with his dynamo, and connect the mug to this hybrid device with a string.

Converting Kinetic Energy to Electrical Energy As the mug falls its weight tugs on the string, causing the winding drum to rotate. When the drum rotates, the dynamo’s magnet spins, creating electrical energy. That’s right, all that’s required to produce electricity is a spinning magnet and coils of wire, as explained in my previous blog, Coal Power Plant Fundamentals – The Generator. Now we’ll connect a 5 Watt bulb to the dynamo’s external wires. The Watt is a unit of electrical energy named in honor of James Watt, a pioneer in the development of steam engines in the late 18th Century. Now it just so happens that 1 Watt of electricity is equal to 1 Joule of energy per a specified period of time, say a second. This relationship is expressed as Watt • second. Stated another way, 4.9 Joules converts to 4.9 Watt • seconds of electrical energy. Let’s see how long we can keep that 5 Watt bulb lit with this amount of energy. Mathematically this is expressed as, Lighting Time = (4.9 Watt • seconds) ÷ (5 Watts) = 0.98 seconds This means that if the mug’s kinetic energy was totally converted into electrical energy, it would provide enough power to light a 5 Watt bulb for almost 1 second. Next time we’ll see what happens to the 4.9 Joules of kinetic energy in our coffee mug when it hits the floor and becomes yet another form of energy. Copyright 2015 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE Engineering Expert Witness Blog ____________________________________ |

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

Published by Philip J. O'Keefe, PE, MLE