|

Have you thought about using courtroom visual aids before but didn’t have a clue of where to begin? Many feel that when they were born somehow the creativity bone was left out. As a result, they feel very unsure of themselves and are particularly doubtful about their ability to suggest to an artist what they might need. The difficulty that presents itself is not that they are unaware of what the real cause of the problem is, but rather unsure of how best to portray it to others, say a jury. Those involved in the legal profession know that courtroom visual aids, a.k.a. courtroom demonstratives, can be effectively used to convey ideas that are easily lost in purely verbal descriptions. But should these be in the form of scale models? Annotated photos? Graphic art renditions? Computer Aided Design (CAD) drawings? No need to worry, this is the territory of the visual artist, well trained in perspective. I recently received a call from an attorney client who was representing a worker who was severely injured in an industrial accident. The situation involved the operation of material handling equipment which was much too large to bring into the courtroom. And it was also far too complex to sufficiently depict its operation through the use of photographs or videotaping. After gathering details about the accident, I determined that showing the jury a 1/20 scale model of the equipment as a whole would be the ideal way for the attorney to begin telling the story. This model would be used in conjunction with a much larger and fully operational 1/4 scale model of the key portion of the equipment that is held to have failed. This larger model would serve as a spotlight on the area in question, enabling the jury to zero in on specific details. And because it was fully operational, the attorney could demonstrate the precise sequence of events that led up to the injury. The jury might even be allowed to manipulate the mechanism themselves to gain an even better understanding. In addition to these physical models, a graphic illustration would be used to illustrate the hazardous condition that existed immediately before the accident and how this led to the worker’s injuries. This final piece in the visual aid puzzle would serve to tie all the elements together. No matter what the situation, a visual courtroom demonstrative can be devised to bring the situation at hand into graphic light, where its message can be easily absorbed by all. _________________________________________________________________ |

Archive for the ‘Courtroom Visual Aids’ Category

The Birth Of A Courtroom Visual Aid

Sunday, September 6th, 2009A Picture Is Worth A Thousand Of Them

Sunday, August 2nd, 2009|

Maybe more? Take the Mona Lisa. Who hasn’t gazed into the eyes of this mysterious female and wondered what she’s thinking, what da Vinci thought as he painted her? And yet, although the questions are many, the image speaks for itself and words seem unnecessary. The mood is clear, the emotional effect visceral. Words would only muddy the waters. And remember the last time you stood in front of an exhibit at the science museum, the one depicting the passage of time since Earth’s formation? Remember that small segment which represented the age when humans were introduced into the mix? Would the words, “humans are thought to have appeared a mere 200,000 years ago, while the Earth is said to be millions of years old,” produce the same effect? Now let’s switch tracks to something less beautiful, yet even more powerful, the photos of a crime scene. There’s a reason those photos are introduced to a jury. The reason has to do with the power of images that transcends all words. Courtroom visual aids introduced to juries in civil cases can be just as powerful. These visual aids could include annotated photographs from a forensic engineering inspection, technical illustrations showing the motion of a complicated mechanism, or scale models that put very large or very small objects into perspective. We live in the Visual Age, there’s no denying it. And studies show that attention spans just keep getting shorter. So the next time you want to get your message across, don’t tell them what you want them to know, show them. Give them something interesting to look at! ____________________________________________________________________ |

Finite Elements Analysis (FEA)

Wednesday, July 8th, 2009|

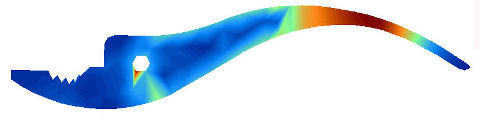

Perhaps you have come across references to “Finite Elements Analysis,” or “FEA,” and wondered what it meant. In the world of engineering, FEA is used to analyze stresses and strains within mechanical component and structural elements. The results of FEA can then be used by an engineering expert witness as an effective demonstrative to convey highly technical concepts to a jury in an easily understood and visually appealing way. In order to conduct FEA, engineers use software to create models of mechanical components. These models are based on scale drawings of the components. Each model includes the physical constraints and material properties of the actual component. After a model is complete, the engineer subjects it to simulated forces. The software creates a colorful map of the results. (See the example below.) The colors represent different stress intensity levels. Blue is an area of low stress and red is an area of high stress. In other words, a red region is where the part is more likely to fail.  FEA of a Plier Handle In a product liability or personal injury lawsuit, the results of FEA can be used in the courtroom to show areas on a machine part where it can become deformed or fracture due to forces placed upon it. FEA can be also be used in patent infringement lawsuits to demonstrate to the jury how a mechanical component in a device actually performs differently from an element in the claimed invention.

___________________________________________________________________

|

The Most Effective Expert Witness Is Born, Not Made

Wednesday, July 1st, 2009 Can there be any question about the fact that credibility is at the heart of every lawsuit? There is no argument that attorneys must appear credible to the jurors and that the evidence they present must be deemed credible. And those that are called to the stand to act as witnesses or experts must, undoubtedly, also be credible. So what makes for a credible expert witness? It may not be what you first think, for although the best expert witnesses demonstrate an uncanny natural ability to teach, they are, by and large not PhD’s, that is to say, they are not professional teachers. Jim McElhaney, senior editor and columnist for Litigation, the journal of the ABA Section of Litigation and author of the article, “Put Simply, Make Your Experts Teach,” which appeared in the May, 2008, ABA Journal may say it best:

In other words, the most effective expert witnesses: 1) Are down-to-earth … people who the jurors can relate to; 2) Are able to convey their message in everyday language, not the jargon of their profession, because people cannot accept as truth what they don’t understand; 3) Are effective at explaining things and enjoy demonstrating to others how things work; 4) Are able to tell a story, paint a picture, whatever it takes to enable the jurors to visualize the point; 5) Will know how to use visual aids, that is, demonstratives, to make the case facts come alive, because jurors need to “see” the facts. In short, your best expert is someone who is an artist capable of explaining the facts, however technical, in the most visual way possible. |