|

Are you familiar with the adage, “Things are not always as they seem”? It’s probably come into play in your life at one time or another, like when you opted to buy the cheapest model of something, only to find out that its life span was two weeks before falling apart. Not such a bargain after all. Well, it’s kind of that way with low sulfur coal and its application in electric power production. All coals contain some sulfur, their content ranging from trace amounts to as high as 8%. This sulfur ends up as a byproduct of the combustion process, meaning it is released into the atmosphere when coal is burned. There it combines with moisture in the air to form sulfuric acid. If you will remember from last week’s blog, this is the stuff that forms acid rain, able to dissolve marble statues, corrode metal, and disrupt eco systems. In the process of generating electricity for homes and businesses, many utility power plants of the past burned coal with high sulfur content. This was the case through the middle of the 20th Century. This coal was brought into power plants by trains and river barges from nearby coal mines. In some cases power plants were actually built next to the mines, thereby eliminating shipping cost. It was effective and cheap. Then, in 1963, the Clean Air Act was signed into law, its purpose to improve, strengthen, and accelerate programs for the prevention of air pollution. By 1970 the Act had empowered the federal government to set and enforce national air quality standards for sources of air pollution, like coal burning power plants. Under the Clean Air Act, government was able to mandate to utilities that they reduce sulfur emissions or face court injunctions to shut them down. Caught between a rock and a hard place, utilities learned to comply, switching over to lower sulfur coals. But the story doesn’t end here. That lower sulfur created a whole host of new problems, for the power plant and their consumers. To begin with, low sulfur coals are scarce in areas of the country where electricity is needed most, like the densely populated eastern half of the country. It has to come from mines in the western states like Wyoming, and for a power plant located in Chicago, for example, this can get costly. A lot more costly than simply getting the coal, high sulfur content coal, that is, from nearby mines in southern Illinois. The result is higher transportation costs, and this cost is passed on to consumers. Another problem with low sulfur coals is that they tend to release less heat energy than higher sulfur coals when they are burned. That means that you have to burn more of it to generate the same amount of power. As a result, utilities ended up having to buy more coal, another cost that was passed on to the consumer. Yet another issue with the switch from high sulfur to low sulfur coals involved the reconfiguration of power plants that was made necessary. You see, when power plant boilers are designed, they have a particular type of coal in mind, and that originally was high sulfur coal. In addition, many power plants have been required to install equipment to scrub sulfur from the gases produced when the coal is burned. This scrubbing equipment is expensive to purchase, install, and operate. Pollution control equipment like this consumes power, but it does not facilitate the process of generating electricity. In addition to these costs, the switch to low sulfur coal causes many other problems that can raise the cost of operations and make the power plant less reliable. For example, some low sulfur coals have properties that tend to make ash stick to the surfaces inside of boilers, often leading to boilers overheating and springing leaks. If these leaks are bad enough, the boiler has to be shut down for cleaning and repair, and when this happens the electrical generating unit has to be taken off the utility grid. The net result is less power being available to meet consumer demand. We can thank the Clean Air Act for effectively reducing the amount of airborne pollutants, but we must acknowledge the cost to do so. Electric utilities are for-profit corporations, not charities, and someone has to pay for the increased coal consumption, higher transportation costs, equipment additions, and operating problems that are a result of the usage of low sulfur coal. That someone is the consumer. _____________________________________________ |

Posts Tagged ‘electric utility’

Alternative Energy Sprawl

Sunday, May 2nd, 2010|

The last few weeks we’ve been discussing some of the technical and environmental drawbacks of alternative sources of electrical energy and nuclear power generation. This week we’ll take a look at another drawback, that of energy sprawl.

So what exactly is “energy sprawl?” It’s an easily understand concept, but one that is often overlooked by proponents of the alternative energy movement. Energy sprawl is simply the amount of land which is taken over by alternative power sources in order to generate a given amount of electricity, and that number is dauntingly large.

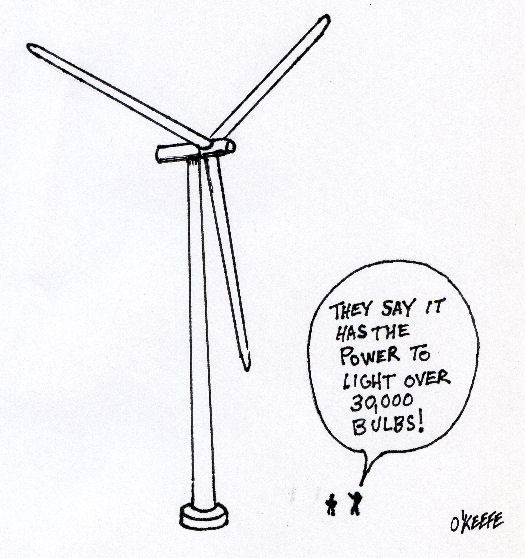

For example, let’s revisit the subject of wind turbines. According to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) of the U.S. Department of Energy, each turbine is to be spaced five to ten turbine diameters apart in a wind farm, depending on local conditions. Now the blades of a 2 megawatt (2 million watt) wind turbine are about 260 feet in diameter, and for our example we’ll space them at the prescribed minimum distance of five diameters. The math for this one is easy, 260 times five, which equates to spacing of 1333 feet, or just over a quarter of a mile. That’s right, if you build a wind turbine farm with a whole bunch of these 2 megawatt turbines, they’ll have to be spaced a minimum of a quarter mile apart. You’ll need a lot of acreage.

So based on the calculations above, we’d have to build a wind farm where each 2 megawatt turbine is surrounded by a circle of empty land 1333 feet in radius. We know from geometry that the area of a circle can be calculated by multiplying pi, that is 3.1416, times its radius squared, and this translates into a minimum area of about 5.6 million square feet per 2 megawatts of power generated, or about 2.8 million square feet per megawatt. Just to put this into perspective, a football field has an area of 57,564 square feet. So what we’re actually talking about here is a little more than 48 football fields worth of land per megawatt of electricity generated!

Let’s turn our attention now to solar power generation. We want to generate electricity with their photo-voltaic (PV) panels, and these panels are made of special materials that convert the sun’s energy directly into electricity. Great concept, but here again we’re talking a lot of land. According to the NREL, it’s estimated that 6.4 acres are required to generate 1 megawatt of electricity using PV panels. Since one acre equals 43,560 square feet, we’d need a total of 278,784 square feet of land area per megawatt. After we’ve done the math we discover that this equates to almost five football fields of area per megawatt of electricity generated.

We’ve now established that loads of land space is required to operate multiple options for alternative energy, and you’re probably wondering how this all compares to land usage for fossil fuel (i.e. coal, oil, natural gas) and nuclear power generation. Well, a typical 1000 megawatt coal fired power plant occupies about 148 million square feet. This translates to around 148,000 square feet per megawatt, which is just over two and a half football fields per megawatt. As for a 1000 megawatt nuclear power plant, we’re talking about 28 million square feet that’s typically occupied by an operating plant, and that translates to almost 28,000 square feet per megawatt, or a little less than half of a football field per megawatt.

Math established, it’s a hands down victory for fossil fuel and nuclear plants compared to wind turbine and solar energies when it comes to land usage. Last time I checked tillable land acreage was going down, not up, around cities where electricity demand is highest. Do we start pushing farther outward to build wind turbine and PV farms on vast expanses of land currently occupied by forests or used to grow our food? Which would you rather do, eat or have electricity?

_____________________________________________

|

Nuclear Power, Is It The Answer?

Sunday, April 18th, 2010|

In weeks past we’ve explored wind energy and the possibility of it overtaking fossil fuel burning plants as our main source of power. This week we’ll discuss the next most viable option to do the job, that of nuclear power. Nuclear power, unlike fossil fuel plants, doesn’t combust fuel and therefore doesn’t contribute to air pollution. But unlike wind turbines, their electrical output is reliable, that is to say, we know, save for a major breakdown, that they will put out X-amount of power every day, regardless of weather conditions. As a matter of fact, according to the Nuclear Energy Institute, the 103 nuclear power plants in operation in the United States today are the most reliable and efficient producers of energy to our electric power grid. They account for about 20% of the power generated and produce a total capacity of 96.245 gigawatts, meaning, a whopping 96.245 billion watts. Nuclear energy is clean, reliable, and produces loads of power, so why not initiate a program to begin immediate replacement of our dirty fossil fueled plants? It’s time to take a closer look. Needless to say, large scale replacement of fossil fueled power plants with nuclear power plants would be a huge undertaking. You’ll remember from my previous blog postings that the US Department of Energy reports that 71.2% of our power is currently being produced by burning fossil fuels. All power plants, and especially nuclear power plants, are extremely expensive to build. Let’s look at an example. In 2007, Florida Power & Light informed the Florida Public Service Commission that the cost to build a new nuclear plant in south Florida would be approximately $8,000 per kilowatt-hour. How does this large sum affect the consumer in terms of real dollars? Well, let’s say you want to build a 3,000 megawatt (3,000 million watt) nuclear plant. This is enough capacity to provide power for about 2 million people in the US. When all is said and done, you’ll end up having to pay out $24 billion before you can start generating electricity. That looks like a lot of cash outlay for one plant, but what does it mean to each individual? If we do the math, a nuclear plant that is capable of supplying 2 million people with electricity will result in a cost of approximately $12,000 per person. Considering that, will investors, taxpayers, and consumers be willing to cover the losses that accrue when all existing fossil plants are closed and nuclear plants are erected to replace them? As with wind powered energy, cost is an enormous factor when considering the viability of nuclear power plants, but there is something way more profound to consider. Nuclear power plants produce radioactive waste. This waste remains radioactive, and therefore highly poisonous to the environment, for millions of years. That’s right, millions, not hundreds, not thousands, millions of years. The Nuclear Energy Information Service states that for each nuclear reactor that exists, 50 to 60 tons of high level radioactive waste is produced every year. So you’ve got all this waste as a byproduct of nuclear energy production, and, of course, there’s a lot of controversy surrounding its safe disposal. Not only does it lay around for millions of years, the costs of dealing with it are staggering. The US Department of Energy estimated in 2008 that it will cost around $96 billion to construct the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository in Nevada, which is basically a huge underground garbage dump for nuclear waste. And this amount of money will only keep it in operation for about 150 years. What happens after that? And if we build more nuclear plants in addition to those that currently exist, what will then be the cost of disposing of their waste? No one knows for sure, but they know it’s a mighty large sum, and certainly much too large for the ailing American economy to absorb. Now, Dr. Seuss, the guy that wrote The Cat in the Hat and other wonders, was an actual person, and he had a lot to say about things that didn’t involve gnarly looking creatures that go “BUMP!” in the night: “Sometimes the questions are complicated and the answers are simple.” Well, that’s sort of the case here. There are a lot of seemingly simple answers being posed to address our energy and environmental problems, but when you start asking pointed questions to delve deeply into the feasibility of those answers, things can get extremely complicated. We have seen through our present blog series that these answers inevitably lead to more questions and a multiplicity of other problems, and so far we haven’t seen an easy fix to our energy issues. But are we just making an issue where none exists? Are we making a mountain out of a mole hill? Next week we’ll explore a few more options that are being considered as alternative energy sources. Perhaps there is an easy answer to our power dilemma. _____________________________________________ |

Alternative Energy And Its Impact On Our Electrical Grids

Sunday, April 11th, 2010|

This week’s blog is a re–publication of a web article by Alex Salkever which appeared on April 6, 2010, in Daily Finance, an AOL Money and Finance site. It’s an excellent followup to last week’s blog on wind turbine energy, which raised concerns as to the feasibility of its widespread use. It’s always good to have multiple sources of information when assessing the value of anything, such as when you seek a doctor’s second opinion, and this article serves that purpose. Enjoy! Too Green, Too Soon? Renewable Power May Destabilize Electrical Grid By Alex Salkever Boy, that was fast. Only five years into the world’s renewable energy push, many utility companies are so concerned about grid instability that they’re saying they can’t accept any more electricity from intermittent sources of power. Translation: Solar power only runs in the day time and can’t re relied on for so called “baseload” capacity. Wind power primarily produces current at night and, likewise, can’t be relied upon for baseload capacity. Geothermal, meanwhile, is perfect for providing baseload. But geothermal projects take an excruciatingly long time to build out. And then there have been the recent spate of earthquake scares around geothermal sites. The upshot: Utilities such as Hawaiian Electric in President Obama’s home state are voicing concerns about plans to integrate more solar and wind power into the grid until they develop methods to more effectively absorb intermittent sources of power without destabilizing the whole shebang. In Europe, Czech utility companies are concerned that “feed-in tariffs,” which require power companies to repurchase all home- and business-generated renewable power at elevated rates, might wreak havoc on the Central European grid. This growing push-back from utilities could prove to be shock to energy project developers, lawmakers and homeowners. In the U.S., project developers and state lawmakers have assumed that the ambitious laws mandating as much as 40% of some states’ power come from renewable sources within the next few decades would ensure huge demand for green power as utilities scaled up their use of such resources from low single-digit levels. Likewise, homeowners have tended to assume that if they could put a panel on their roof (or a windmill on their property), they would be guaranteed a market for the extra power produced. Storing Excess Power in Ice, Salt or Even … Caves? The ability to sell back power to a utility at retail rates (meaning the rates they charge the public) is dubbed “net metering,” and many states have limitations on what percentage of total baseload power on a grid a utility must buy back. It was broadly assumed net metering would go away in hurry when the Green Revolution came of age. Now, that appears unlikely. The alleged problems with absorbing intermittent green power point to a more fundamental issue with the existing power grid — namely, that the system isn’t really ready to handle a significantly more distributed power production footprint. One possible remedy would be for utilities to build more power storage systems, and many new forms for those are on the drawing boards. One solution could be massive battery installations from the likes of A123 Systems. Another could be a system such as that offered by Ice Energy, which uses cheap power at night to make ice, reducing the power requirements of air conditioning systems in the daytime. This effectively arbitrages the price differential between nighttime and daytime power generation — something that potentially could be a huge boon for wind power. Other, more exotic “battery” systems that have been proposed include storing power in molten salt or injecting compressed air into sealed caves, both of which create potential energy that can later be used to power electric generators. Power storage is already being recognized as essential to new renewable energy projects. A wind farm on Maui will be the first in the country to have an added power storage component in the form of a bank of lithium-ion batteries. But most green power developers are still having trouble competing with coal and natural gas fired plants on a level playing field — even without adding in the costs of power storage. If the issues of dealing with intermittent power sources are as disruptive to grid stability as some traditional utilities are claiming, the Green Revolution may be a case of “too much, too soon” — at least until the engineers can figure out better, cheaper ways to capture sunshine and wind in a bottle. From DailyFinance: http://srph.it/dAoxAj _________________________________________________________________ |

Wind Turbine Energy, Is It The Answer?

Sunday, April 4th, 2010|

Alternative energy is a hot topic today. There are certainly benefits to be gained by replacing fossil fueled power plants with alternative energy sources. One of the most publicized of these is the free energy that is generated by wind turbines that drive electric generators. Surely this is a win-win situation? Let’s take a closer look! If you’ve been out in the country within the last few years you’ve surely seen the new generation of windmill. These mammoths are so large and intimidating they remind me of the cartoon robot, Gigantor, popular back in the 1960s—scary until you get to know him. Yes, these wind turbines are big, and so is their cost. They are so expensive that a return on investment is a rather long way off. Let’s examine the numbers. A 2 megawatt wind turbine can cost over $2 million to purchase and install. By 2 megawatt, I mean two million watts of output. The generator on this baby can produce enough power to light around 33,330 sixty watt bulbs. If I were to install one on my property, my local electric utility would be willing to pay me approximately $10,000 per month to buy its power from me. At this rate of compensation, it would take over 16 years to realize a return on my investment. That’s the “looks good on paper” figure. Realistically speaking, it would actually take a lot longer than 16 years if we factor in the cost of maintenance and the interest rates on borrowed money. So what happens if the Gigantor in your back yard needs servicing? I did some checking, and it’s not cheap. It can cost as much as $15,000 just to hire the massive crane that is required to lift the heavy parts involved. Aside from purchase price and maintenance expenses, another thing to consider when talking installation of wind turbines is the fact that they operate at the mercy of Mother Nature. No wind, no power. Is there anything we can do to compensate for this factor, like store the energy generated on a windy day for future usage? This would be a great solution, if only battery technology was economical enough for storage of the vast amounts of energy that is required to power an electric utility grid if the wind stops blowing for an extended period of time. For example, sodium battery technology is up to the task, but the cost is high, at around $3,500.00 per kilowatt-hour. At this price a 2 megawatt wind turbine would need about $7 million worth of storage just to get us through about one hour of calm weather! Now here’s a proposed solution to the storage issue that you may have read about. It involves utilizing storage systems which would use electric motors to convert the electrical energy from the turbine generators into mechanical energy. This energy would then be transferred to mechanical storage devices, such as a huge flywheel. Then, if the wind stops blowing and power stops flowing, the motor on the flywheel can be turned into an electric generator. The mechanical energy stored in its spinning mass would power the generator, which would in turn keep electricity flowing into the power grid. Now remember, the amount of mechanical energy we can store in a flywheel spinning at a given speed depends on its mass, that is, how heavy it is. The more energy we have to store, the heavier the flywheel has to be. So when we’re talking about storing many millions of watts of energy to get us through several days of calm weather, we’d have to make a flywheel so massive it would be impractical and uneconomical to build. Just to store about one hour’s worth of energy from our 2-megawatt wind turbine we’d need to build a flywheel over 65 feet in diameter that spins at 1800 rpm and weighs more than 9 tons. Another proposal to store the wind turbine’s energy involves the use of electric motors to drive air compressors that would pressurize caverns deep below the earth’s surface. This effectively creates what is called a compressed-air energy storage (CAES) facility. The idea here is that when the wind stops, the motors would act as generators and the compressors would act as air turbines. This pressurized air could then be drained from the caverns in which it is stored and redirected to flow through the turbine. Then, finally, the stored mechanical energy in the pressurized air would be converted by the air turbine and generator back into electrical energy to power the grid. At best, a CAES facility will run at about 70% efficiency. That means for every 100 kilowatt-hours of energy you put into storage, you only receive 70 kilowatt-hours in return. Once examined, it seems that current technology does not provide a cost-feasible solution for the replacement of fossil fuel backed energy with wind turbine energy. So where do we go from here? We’ll continue our exploration of alternative energy next week. _________________________________________________________________ |

When It Comes to Energy, There’s No Free Ride

Sunday, March 28th, 2010|

Electric cars are a win-win proposition, right? They’re the solution to many if not most of our vehicle emission problems, right? They’re all good, whereas power derived from petroleum-based fuels is all bad, right? Unfortunately, just as nothing in life is all good or all bad, so goes the reality behind electric cars. Sure, they will most certainly reduce our reliance on foreign oil, which is a good thing, but they also come with some not-so-good things attached to them. Those of us who drive hybrids know that its battery must continually recharge. It is able to do this through various means, many of which take their beginnings in the power that is derived from the fossil fuels that also run the car. So, too, will the batteries that charge electric cars eventually run down, and when they do, they must be plugged into a source of electrical energy to recharge. So where does this electrical energy come from? It comes from an electric utility grid, the same grid that provides powers to our homes and businesses. And this is where the pretty picture converges upon some not so pretty elements, because the utility grid is largely fed by fossil fueled power plants that burn coal, natural gas, and, yes, even oil, the very thing we were trying to get away from when designing the concept for our electric cars. Presently, the US Department of Energy reports that 71.2 percent of our power is generated by burning fossil fuels, and ultimately this is what will be providing the power behind electric cars. We all recognize the fact that the smoke that rises from the stacks of fossil fuel plants release pollutants into the environment, and we’re trying very earnestly to do something about that. Would adding pollution control devices to them serve to curb their emissions? Yes, but they would come at a high price as these devices are extremely expensive to build, operate, and maintain. In fact, they are so expensive they would add a hefty price tag to our already high-priced electric utility bills. There’s got to be a better way to make the electricity to power a car, right? What about using alternative energy sources? We’ll explore these options next week. _________________________________________________________________ |

Thermodynamics In Mechanical Engineering, Part II, Power Cycles

Sunday, December 13th, 2009|

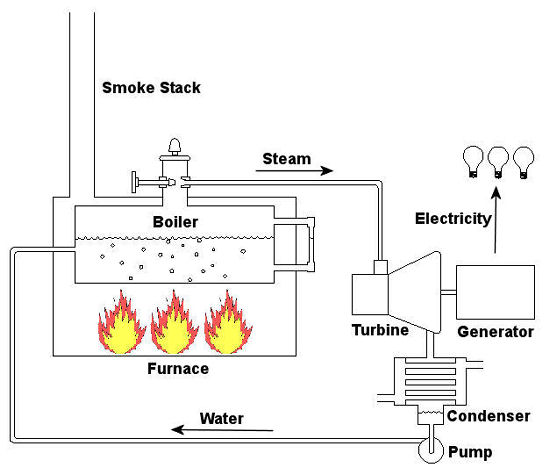

Last time we talked about some general concepts in an area of mechanical engineering known as thermodynamics. In this week’s article we’ll narrow our focus a bit to look at a part of thermodynamics that deals with power cycles. One mammoth example of a power cycle can be found in a coal-fired power plant. You can’t help but notice these plants with their massive buildings, mountains of coal, and tall smoke stacks. They’ve been getting a lot of negative press lately and are a central focus of the debate on global warming, but most people have no idea what’s going on inside of them. Let’s take a peek. Figure 1 – A Coal-Fired Power Plant A power plant has one basic function, to convert the chemical energy in coal into the electrical energy that we use in our modern lives, and it’s a power cycle that is at the heart of this conversion process. The most basic power cycle in this instance would include a boiler, steam turbine, condenser, and a pump (see Figure 2 below). Figure 2 – A Basic Power Cycle When the coal is burned in the power plant furnace, its chemical energy is turned into heat energy. This heat energy and the boiler are enclosed by the furnace so the boiler can more efficiently absorb the heat energy to make steam. A pipe carries the steam from the boiler to a steam turbine. Nozzles in the steam turbine convert the heat energy of the steam into kinetic energy, making the steam pick up speed as it leaves the nozzles. The fast moving steam transfers its kinetic energy to the turbine blades, causing the turbine to spin, much like a windmill (see Figure 3 below). Figure 3 – The Inner Workings of a Steam Turbine The spinning turbine is connected by a shaft to a generator. The turbine works to spin the generator and thus produces electricity. After the energy in the steam is used by the turbine, it goes to the condenser, whose job it is to convert the steam back into water. To accomplish this, the condenser uses cold water, say from a nearby lake or river, to cool the steam down until it converts from a gas back to a liquid, that is, water. This is why power plants are normally found adjacent to a body of water. After things are cooled down, the pump gets to work, pushing the condensed water back into the boiler where it is once again turned into steam. This power cycle keeps repeating itself as long as there is coal being burned in the furnace, the plant equipment is functioning properly, and electrical energy flows out of the power plant. Thermodynamics sets up an energy accounting system that enables mechanical engineers to design and analyze power cycles to make sure they are safe, reliable, efficient, and economical. When all is said and done, a properly designed power cycle transfers as much heat energy as possible from the burning coal on one end of the cycle to meet the requirements for electrical power on the other end of the cycle. As was mentioned in last week’s blog, nothing is 100% efficient. Next time we’ll learn about being cool. No, I’m not going to talk about the latest cell phone gadget or who’s connected on Facebook. We’ll be covering refrigeration cycles. _________________________________________________________________ |