Posts Tagged ‘engineering expert’

Wednesday, May 25th, 2016

|

My activities as an engineering expert often involve creative problem solving of the sort we did in last week’s blog when we explored the interplay between work and kinetic energy. We used the Work-Energy Theorem to mathematically relate the kinetic energy in a piece of ceramic to the work performed by the friction that’s produced when it skids across a concrete floor. A new formula was derived which enables us to calculate the kinetic energy contained within the piece at the start of its slide by means of the work of friction. We’ll crunch numbers today to determine that quantity.

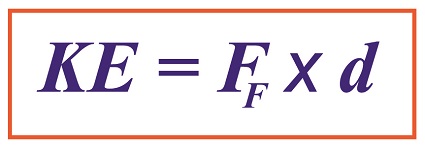

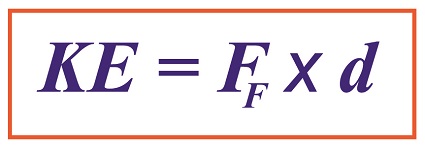

The formula we derived last time and that we’ll be working with today is,

Calculating Kinetic Energy By Means of the Work of Friction

where, KE is the ceramic piece’s kinetic energy, FF is the frictional force opposing its movement across the floor, and d is the distance it travels before friction between it and the less than glass-smooth floor brings it to a stop.

The numbers we’ll need to work the equation have been derived in previous blogs. We calculated the frictional force, FF, acting against a ceramic piece weighing 0.09 kilograms to be 0.35 kilogram-meters/second2 and the measured distance, d, it travels across the floor to be equal to 2 meters. Plugging in these values, we derive the following working equation,

KE = 0.35 kilogram-meters/second2 × 2 meters

KE = 0.70 kilogram-meters2/second2

The kinetic energy contained within that broken bit of ceramic is just about what it takes to light a 1 watt flashlight bulb for almost one second!

Now that we’ve determined this quantity, other energy quantities can also be calculated, like the velocity of the ceramic piece when it began its slide. We’ll do that next time.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: distance, electrical energy, energy, engineering expert, frictional force, kinetic energy, mass, velocity, Watt, work, work of friction, work-energy theorem

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Calculating Kinetic Energy By Means of the Work of Friction

Thursday, May 12th, 2016

|

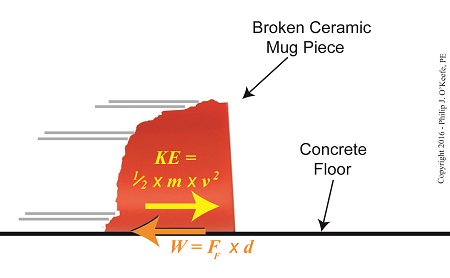

We’ve been discussing the different forms energy takes, delving deeply into de Coriolis’ claim that energy doesn’t ever die or disappear, it simply changes forms depending on the tasks it’s performing. Today we’ll combine mathematical formulas to derive an equation specific to our needs, an activity my work as an engineering expert frequently requires of me. Our task today is to find a means to calculate the amount of kinetic energy contained within a piece of ceramic skidding across a concrete floor. To do so we’ll combine the frictional force and Work-Energy Theorem formulas to observe the interplay between work and kinetic energy.

As we learned studying the math behind the Work-Energy Theorem, it takes work to slow a moving object. Work is present in our example due to the friction that’s created when the broken piece moves across the floor. The formula to calculate the amount of work being performed in this situation is written as,

W = FF ×d (1)

where, d is the distance the piece travels before it stops, and FF is the frictional force that stops it.

We established last time that our ceramic piece has a mass of 0.09 kilograms and the friction created between it and the floor was calculated to be 0.35 kilogram-meters/second2. We’ll use this information to calculate the amount of kinetic energy it contains. Here again is the kinetic energy formula, as presented previously,

KE = ½ × m × v2 (2)

where m represents the broken piece’s mass and v its velocity when it first begins to move across the floor.

The Interplay of Work and Kinetic Energy

The Work-Energy Theorem states that the work, W, required to stop the piece’s travel is equal to its kinetic energy, KE, while in motion. This relationship is expressed as,

KE = W (3)

Substituting terms from equation (1) into equation (3), we derive a formula that allows us to calculate the kinetic energy of our broken piece if we know the frictional force, FF, acting upon it which causes it to stop within a distance, d,

KE = FF × d

Next time we’ll use this newly derived formula, and the value we found for FF in our previous article, to crunch numbers and calculate the exact amount of kinetic energy contained with our ceramic piece.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: distance, energy, engineering expert, frictional force, kinetic energy, mass, velocity, work, work-energy theorem

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on The Interplay of Work and Kinetic Energy

Wednesday, April 27th, 2016

|

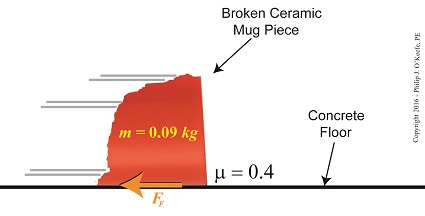

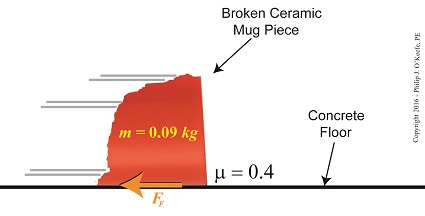

Last time we introduced the frictional force formula which is used to calculate the force of friction present when two surfaces move against one another, a situation which I as an engineering expert must sometimes negotiate. Today we’ll plug numbers into that formula to calculate the frictional force present in our example scenario involving broken ceramic bits sliding across a concrete floor.

Here again is the formula to calculate the force of friction,

FF = μ × m × g

where the frictional force is denoted as FF, the mass of a piece of ceramic sliding across the floor is m, and g is the gravitational acceleration constant, which is present due to Earth’s gravity. The Greek letter μ, pronounced “mew,” represents the coefficient of friction, a numerical value predetermined by laboratory testing which represents the amount of friction at play between two surfaces making contact, in our case ceramic and concrete.

To calculate the friction present between these two materials, let’s suppose the mass m of a given ceramic piece is 0.09 kilograms, μ is 0.4, and the gravitational acceleration constant, g, is as always equal to 9.8 meters per second squared.

Calculating the Force of Friction

Using these numerical values we calculate the force of friction to be,

FF = μ × m × g

FF = (0.4) × (0.09 kilograms) × (9.8 meters/sec2)

FF = 0.35 kilogram meters/sec2

FF = 0.35 Newtons

The Newton is shortcut notation for kilogram meters per second squared, a metric unit of force. A frictional force of 0.35 Newtons amounts to 0.08 pounds of force, which is approximately equivalent to the combined stationary weight force of eight US quarters resting on a scale.

Next time we’ll combine the frictional force formula with the Work-Energy Theorem formula to calculate how much kinetic energy is contained within a single piece of ceramic skidding across a concrete floor before it’s brought to a stop by friction.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: coefficient of friction, Earth's gravity, engineering expert, force of friction, friction, frictional force, frictional force formula, gravitational acceleration constant, kinetic energy, Newtons, weight force, work-energy theorem

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability, Professional Malpractice | Comments Off on Calculating the Force of Friction

Thursday, April 14th, 2016

|

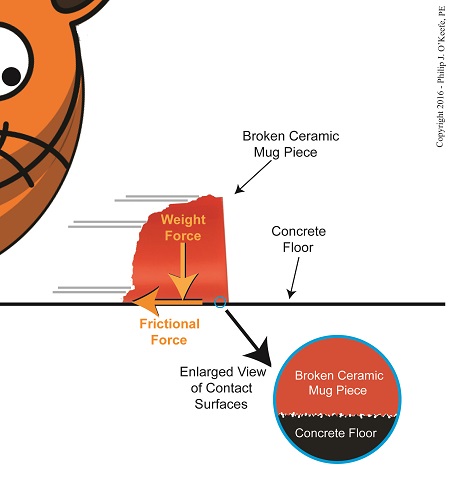

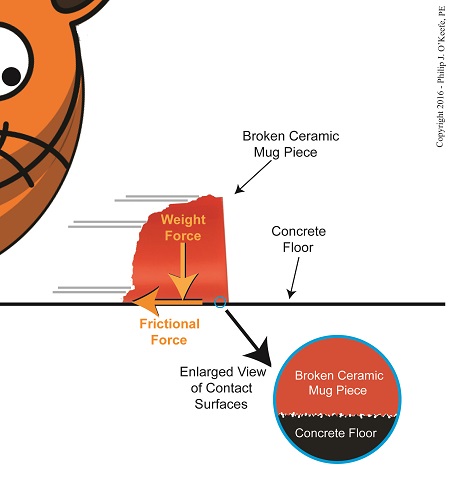

Last time we introduced the force of friction, another force in our ongoing discussion about changing forms of energy, and we learned that it’s often a counterproductive force which design engineers and engineering experts such as myself must work to minimize in order to optimize functionality of devices we’re designing. Today we’ll introduce the frictional force formula, which computes the amount of friction present when two surfaces meet.

To demonstrate frictional force, we’ve been working with the example of a shattered mug’s broken ceramic pieces and watching their progress as they slide across a concrete floor. They eventually come to a stop not too far from the point where the mug shattered, because friction causes them to stop. The mass of the ceramic pieces in combination with the downward pull of gravity causes the broken bits to “bear down” on the floor, thereby maximizing contact and creating friction.

At first glance the floor and mugs’ surfaces may appear slippery smooth, but when viewed under magnification we see that both actually contain many peaks and valleys. The peaks of one surface project into the valleys of the other and it’s fight, fight, fight for the ceramic pieces to continue their progress across the floor. The strength of the frictional force acting upon the pieces is a factor of their individual weights coupled with the roughness of the two surfaces coming into contact — the shattered pieces and the floor. If friction didn’t exist and no other impediments were in the way, the pieces might travel to the next state before stopping!

Frictional Force Resists Motion

Last time we introduced Charles-Augustin de Coulomb, a scientist whose work with friction led to the later development of a formula to calculate it. It’s presented here, and frictional force is denoted as FF,

FF = μ × m × g

where, m is the mass of an object making contact with another surface and g is the gravitational acceleration constant, which is due to the force of Earth’s gravity. The Greek letter μ, pronounced “mew,” represents the coefficient of friction, a number. Numerical values for μ were determined by laboratory testing and are recorded in engineering books for many combinations of materials, including rubber on concrete, leather on steel, wood on aluminum, and our own example of ceramic on concrete.

Next time we’ll plug the numbers that apply to our ceramic-on-concrete example into the friction formula and calculate the frictional force at play.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: Charles-Augustin de Coulomb, coefficient of friction, Earth's gravity, energy, engineering expert, friction, friction force formula, frictional force, gravitational acceleration constant, mass, mu

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on The Frictional Force Formula

Thursday, March 24th, 2016

|

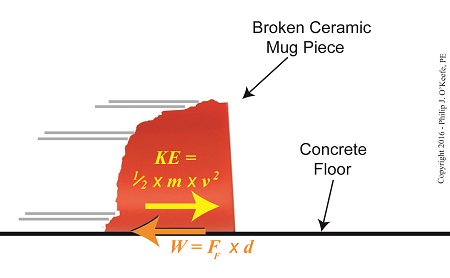

Last time we watched our example ceramic coffee mug crash to a concrete floor, where its freefall kinetic energy performed the work of shattering it upon impact. This is a scenario familiar to engineering experts like myself who are sometimes asked to reconstruct accidents and their aftermaths, otherwise known as forensic engineering. Today we’ll take a look at what happens when the shattered mug’s pieces are freed from their formerly cozy, cohesive bond, and we’ll watch their transmutation from kinetic energy to work, and back to kinetic energy.

As we watch our mug shatter on the floor, we notice that it breaks into different sized pieces that are broadcast in many directions around the point of impact. Each piece has its own unique mass, m, travels at its own unique velocity, v, and has a unique and individualized amount of kinetic energy. This is in accordance with the kinetic energy formula, shown here again:

KE = ½ × m × v2

So where did that energy come from?

The Scattering Pieces Have Kinetic Energy

According to the Work-Energy Theorem, the shattered mug’s freefalling kinetic energy is transformed into the work that shatters the mug. Once shattered, that work is transformed back into kinetic energy, the energy that fuels each piece as it skids across the floor.

The pieces spray out from the point of the mug’s impact until they eventually come to rest nearby. They succeed in traveling a fair distance, but eventually their kinetic energy is dissipated due to frictional force which slows and eventually stops them.

The frictional force acting in opposition to the ceramic pieces’ travel is created when the weight of each fragment makes contact with the concrete floor’s rough surface, which creates a bumpy ride. The larger the fragment, the more heavily it bears down on the concrete and the greater the frictional force working against it. With this dynamic at play we see smaller, lighter fragments of broken ceramic cover a greater distance than their heavier counterparts.

The Work-Energy Theorem holds that the kinetic energy of each piece equals the work of the frictional force acting against it to bring it to a stop. We’ll talk more about this frictional force and its impact on the broken pieces’ distance traveled next time.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: engineering expert, force, forensic engineering, friction force, kinetic energy, kinetic energy formula, mass, velocity, work, work-energy theorem

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Kinetic Energy to Work, Work to Kinetic Energy

Tuesday, March 15th, 2016

|

Last time we watched as the kinetic energy of our falling coffee mug was transformed into the work of creating a crater in a pan of soft kitty litter. Shock absorbing materials are often placed strategically to cushion valuable objects should they fall, and as an engineering expert I’ve sometimes had to implement break-its-fall solutions. Today we’ll place our mug into a less kind scenario, one in which it makes impact with the unforgiving hardness of a concrete floor. In so doing we’ll compare the mug’s ceramic to the floor’s concrete, and we’ll familiarize ourselves with the Mohs Scale of Hardness.

The Mohs Scale of Hardness, Ceramic vs. Concrete

Material hardness is commonly measured by the Mohs Scale of Hardness, which ranks the relative hardness of a material by observing how resistant it is to scratching by other materials harder than itself. This standard was developed by German mineralogist Friedrich Moh in 1812, and it rates objects’ hardness on a scale from 1.0, very soft, to 10.0, very hard. A fingernail, for example, ranks 2.5 on the scale, while a diamond ranks 10.0.

Now let’s take a look at the materials in our scenario, a ceramic mug and concrete floor, and see how they compare. The mug’s ceramic was created by mixing together clay, water, and other materials and then heating them in a kiln, a process known as firing. This firing causes a chemical reaction that bonds the individual materials tightly together, and when it cools it becomes the product we know as ceramic, a hard, brittle solid which registers at about 7.5 on the Mohs Scale.

The floor the mug falls to is poured-in-place cement, a compound consisting of primarily limestone, clay, pebbles and sand. When these materials are combined with water a chemical bonding takes place and forms the hard, stone-like matter we know as concrete, which comes in at about 8.0 on the Mohs Scale.

Although the mug’s ceramic is comparably hard to the floor’s concrete, its inherent brittleness, along with certain design features, most notably its handle, causes it to be fragile. Anyone broken a coffee mug lately?

As for the concrete floor the mug falls onto, it won’t yield to the mug’s freefall kinetic energy and form a crater like the litter did. So where does the mug’s energy go?

According to the Work-Energy Theorem, most of the mug’s kinetic energy is still converted into work, just as it was when it met up with the litter, but because the concrete floor is harder and thicker than the mug’s thin ceramic, the mug’s kinetic energy at impact falls back on itself rather than transferring externally into the concrete. The result is a shattered mug and a mess to clean up.

But we haven’t yet accounted for all the mug’s energy. We’ll find out what happens to the rest of it next time.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: brittleness, cement, ceramic, concrete, energy, engineering expert, force, freefall kinetic energy, hardness, Mohs Scale of Hardness, shatters, work, work-energy theorem

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Mohs Scale of Hardness, Ceramic vs. Concrete

Tuesday, March 1st, 2016

|

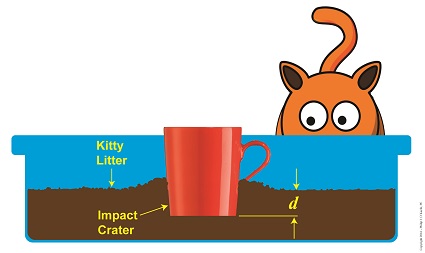

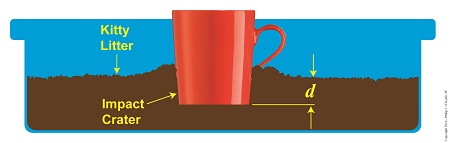

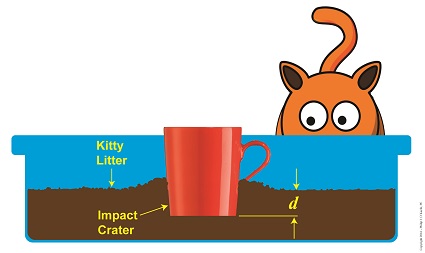

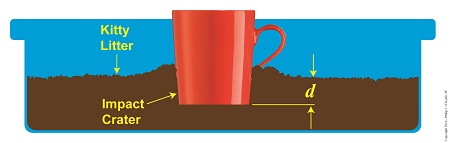

Objects in motion inevitably meet with opposing forces, a theme which I frequently encounter in my work as an engineering expert. Today we’ll calculate the opposing force our exemplar coffee mug meets when it falls into a pan of kitty litter, thus transforming its freefalling kinetic energy into the work required to move through clay litter.

Let’s revisit the Work-Energy Theorem formula, whose terms were explained in last week’s blog,

F × d = – ½ × m × v12 (1)

The left side of this equation represents the mug’s work to move through the litter, while the right side represents its kinetic energy, which it gained through freefall. To solve for F, the amount of force acting in opposition to the mug’s mass m as it plows a depth d into the litter, we’ll isolate it on one side of the equation, as shown here,

F = [- ½ × m × v12 ] ÷ d (2)

So how do we solve for F when we don’t know the value of v1, the mug’s freefall velocity at impact? We’ll use the fact that The Law of Conservation of Energy tells us that all energies are equal, and we’ll eliminate the part of Equation (2) that contains this unknown variable, that is, the right side of the equation which deals with kinetic energy. In its place we’ll substitute terms which represent the mug’s potential energy, that is, the latent energy held within it as it sat upon the shelf prior to falling. Equation (2) then becomes,

F = [- m × g × h] ÷ d (3)

where g is the Earth’s acceleration of gravity factor, a constant equal to 9.8 meters/sec2 , and h is the height from which the mug fell.

Kinetic Energy Meets With Opposing Force

So if we know the mug’s mass, the distance fallen, and the depth of the crater it made in the litter, we can determine the stopping force acting upon it at the time of impact. It’s time to plug numbers.

Let’s say our mug has a mass of 0.25 kg, it falls from a height of 2 meters, and it makes a crater 0.05 meters deep. Then the stopping force acting upon it is,

F = [- (0.25 kg) × (9.8 meters/sec2) × (2 meters)] ÷ (0.05 meters)

= – 98 Newtons

The mug was subjected to -98 Newtons, or about -22 pounds of opposing force when it fell into the litter, that resistance being presented by the litter itself.

Next time we’ll see what happens when our mug strikes a hard surface that fails to cushion its impact. Energy is released, but where does it go?

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: distance, engineering expert, falling objects, force, kinetic energy, law of conservation of energy, mass, Newtons, potential energy, velocity, work-energy theorem

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on When Kinetic Energy Meets With Opposing Force

Thursday, February 18th, 2016

|

It’s not uncommon in my work as an engineering expert to encounter a situation in which I’m missing information. At that point I’ve got to find a creative solution to working the problem. We’ll get creative today when we combine the Law of Conservation of Energy and the Work-Energy Theorem to get around the fact that we’re missing a key quantity to calculate forces exerted upon the falling coffee mug we’ve been following in this blog series.

Last time we applied the Work-Energy Theorem to our mug as it came to rest in a pan of kitty litter. Today we’ll set up the Theorem formula to calculate the force acting upon it when it meets the litter. Here’s where we left off,

F × d = –½ × m × v12

where, F is the force acting to slow the progress of the mug with mass m inside the litter pan. The mug eventually stops and comes to rest in a crater with a depth, d. The left side of the equation represents the mug’s work expenditure, as it plows through the litter, which acts as a force acting in opposition to the mug’s travel.

Kinetic Energy Meets Up With Displacement

The right side of the equation represents the mug’s kinetic energy, which it gained in freefall, at its point of impact with the litter. The right side is in negative terms because the mug loses energy when it meets up with this opposing force.

Let’s say we know the values for variables d and m, quantities which are easily measured. But the kinetic energy side of the equation also features a variable of unknown value, v1, the mug’s velocity upon impact. This quantity is difficult to measure without sophisticated electronic equipment, something along the lines of a radar speed detector used by traffic cops. For the purpose of our discussion we’ll say that we don’t have a cop standing nearby to measure the mug’s falling speed.

If you’ll recall from past blog discussions, the Law of Conservation of Energy states that an object’s — in this case our mug’s — kinetic energy is equal to its potential energy. It’s this equivalency relationship which will enable us to solve the equation and work around the fact that we don’t have a value for v1.

We’ll do the math and plug in the numbers next time.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: displacement, engineering expert, falling objects, impact force, kinetic energy, law of conservation of energy, mass, opposing force, potential energy, velocity, work-energy theorem

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Combining the Law of Conservation of Energy and Work-Energy Theorem

Monday, February 8th, 2016

|

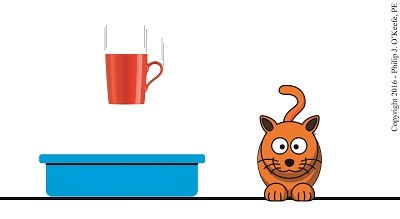

So far we’ve applied the Work-Energy Theorem to a flying object, namely, Santa’s sleigh, and a rolling object, namely, a car braking to avoid hitting a deer. Today we’ll apply the Theorem to a falling object, that coffee mug we’ve been following through this blog series. We’ll use the Theorem to find the force generated on the mug when it falls into a pan of kitty litter. This falling object scenario is one I frequently encounter as an engineering expert, and it’s something I’ve got to consider when designing objects that must withstand impact forces if they are dropped.

Applying the Work-Energy Theorem to Falling Objects

Here’s the Work-Energy Theorem formula again,

F × d = ½ × m × [v22 – v12]

where F is the force applied to a moving object of mass m to get it to change from a velocity of v1 to v2 over a distance, d.

As we follow our falling mug from its shelf, its mass, m, eventually comes into contact with an opposing force, F, which will alter its velocity when it hits the floor, or in this case a strategically placed pan of kitty litter. Upon hitting the litter, the force of the mug’s falling velocity, or speed, causes the mug to burrow into the litter to a depth of d. The mug’s speed the instant before it hits the ground is v1, and its final velocity when it comes to a full stop inside the litter is v2, or zero.

Inserting these values into the Theorem, we get,

F × d = ½ × m × [0 – v12]

F × d = – ½ × m × v12

The right side of the equation represents the kinetic energy that the mug acquired while in freefall. This energy will be transformed into Gaspard Gustave de Coriolis’ definition of work, which produces a depression in the litter due to the force of the plummeting mug. Work is represented on the left side of the equal sign.

Now a problem arises with using the equation if we’re unable to measure the mug’s initial velocity, v1. But there’s a way around that, which we’ll discover next time when we put the Law of Conservation of Energy to work for us to do just that.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: energy, engineering expert, falling objects, Gaspard-Gustave de Coriolis, impact forces, kinetic energy, law of conservation of energy, work, work-energy theorem

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury | Comments Off on Applying the Work-Energy Theorem to Falling Objects

Friday, January 29th, 2016

|

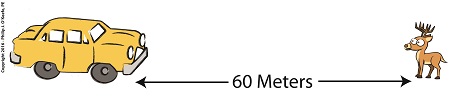

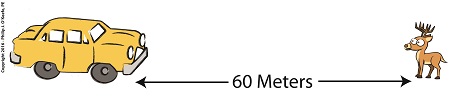

I’m sometimes called upon to render an engineering expert opinion on auto accidents, and in our last blog we stretched this application to a scenario in which Santa’s sleigh collided with the opposing force of a strong wind. At that time we used the Work-Energy Theorem to calculate the amount of food energy Rudolph and his team required to regain speed and get back on schedule. Today we’ll use the Theorem to analyze the forces at play in another deer scenario and calculate the braking distance a car needs to avoid hitting one on the highway.

The average sedan has a mass of about 1,500 pounds, or 680 kilograms. In our example it’s driving down the highway at a speed, or velocity, of 30 miles per hour, which equates to it covering a distance of 13.3 meters, or just under 44 feet, per second.

A deer jumps onto the highway, 60 meters in front of the car. The alert driver slams on the brakes, which exert 1200 Newtons of stopping force on the car. If you’ll recall from past blogs in this series, the Newton is the metric unit used to measure force.

What is Safe Braking Distance? What is Safe Braking Distance?

Did Bambi survive? Let’s use the Work-Energy Theorem to find out. Here it is again,

F × d = ½ × m × [v22 – v12]

where, F is the braking force used to slow a car of mass m, from an initial velocity of v1 to a final velocity of v2 in a braking distance, d. The car will eventually come to a complete stop as the driver attempts to avoid hitting the deer, so its final velocity, v2, will be zero. The Work-Energy Theorem is most often stated in terms of metric units, the measuring unit of choice in the scientific community, and we’ll follow suit with our math.

Inserting these values into the equation, we get,

[1200 Newtons] × d

= ½ × [680 kilograms] × [(0)2 – (13.3 meters per second)2]

Using algebra to solve for d, the braking distance, we arrive at,

d = ½ × [680 kilograms] × [(0)2 – (13.3 meters per second)2] ÷ [1200 Newtons]

d = 50.11 meters

The car stopped 50.11 meters from the point when the driver slammed on his brakes, just about 10 meters short of hitting the deer. Bambi lives to leap another day!

Next time we’ll use the Work-Energy Theorem to assess the fate of the falling coffee mug we introduced in past blogs when we opened our discussion on the different forms of energy.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: automobile, braking distance, braking force, engineering expert, mass, Newtons, velocity, work-energy theorem

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Personal Injury | Comments Off on Applying the Work-Energy Theorem to Braking Distance