| When something is said to be the “heart of the operation,” one usually imagines that it is integral to whatever is being discussed, and it is probably centrally located. The human heart fits this description well. This amazing organ, centrally located within your chest cavity, moves blood, nutrients, oxygen, and carbon dioxide through your body with amazing efficiency. During a twenty four hour period it can pump as much as 2,000 gallons of blood through 6,000 miles of arteries, veins, and capillaries.

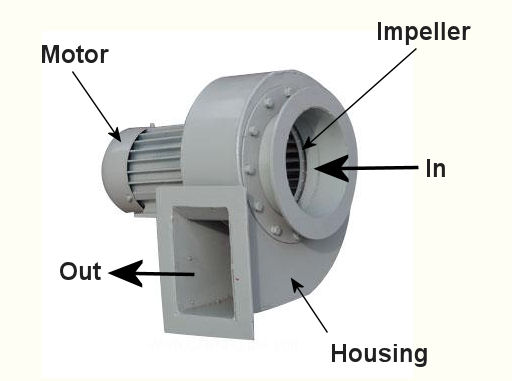

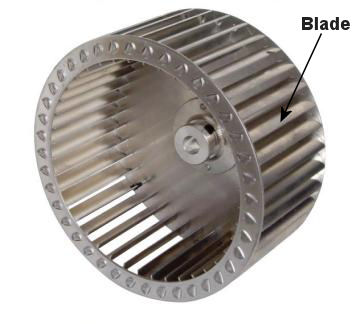

At the heart of a local exhaust ventilation system is its fan. Like the human heart, it is a model of efficiency. It first creates a vacuum in the intake hood, which is strategically located at a pollution source, pulling in contaminated air and leading it through ductwork. Sometimes the fan leads the air to a filter or other air cleaning equipment, but eventually the dirty air is exhausted through a stack leading outdoors. There are two main types of fan, axial and centrifugal. You’re probably most familiar with the axial type, because they’re the type commonly used in tabletop, box, and oscillating fans in your home. These have blades that look like a propeller on an airplane, and they work by drawing air straight through the fan. As helpful as they are within a personal setting, axial fans are not typically used in local exhaust ventilation systems because the electric motor that drives the blades is in the path of airflow. This setup can create a problem if the air flowing over the motor contains dust and flammable vapor. Dust can cause the motor to get dirty and overheat. Flammable vapor can ignite if the motor wiring fails and creates an electrical arc. Because of the technical difficulties presented by an axial type fan, centrifugal fans are what are most often used in industrial settings. One such fan is shown in Figure 1. Figure 1 – Centrifugal Fan The blades of a centrifugal fan are fully enclosed in air tight housing. This housing keeps any dust or fumes from leaking out into the building. The electric motor that drives the fan can be safely located outside of this housing, where it is dust-free and there are no flammable vapors. If you look inside the housing you will see that the moving part, known as the impeller, resembles a squirrel cage. See Figure 2. Figure 2 – Centrifugal Fan Impeller This impeller is made up of many blades, set up within a wheel configuration. When an electric motor causes the wheel to rotate, air is made to move off the blades and out of the impeller due to centrifugal force. This air is sent crashing into the fan housing, shown in Figure 1, which is curved like a spiral to direct the air into an outlet duct which is connected to ductwork that leads to the exhaust stack. As air leaves the impeller, more air rushes into its center from the inlet duct to occupy the empty space that’s been created. Hence, as long as the motor keeps spinning the impeller, air will flow through the fan. In order for all this to work effectively, the centrifugal fan must be the right size, one that is capable of providing enough suction to capture contaminated air at the hood source, then overcoming the resistance to air flow that is presented by ductwork, filters, and other air cleaning devices. Because air resistance factors such as these impede the fan’s ability to move air through the system, the fan must be of sufficient strength make up for these factors. To size up the right centrifugal fan for the job, engineers must calculate the resistance to airflow that is expected to be encountered, and to do this they use data supplied by manufacturers of component parts, as well as tabulated data that is readily available in engineering handbooks. Just as a lawn mower engine won’t provide sufficient energy to power a car, an undersized fan won’t be able to move air through a system which is beyond its capacity limit. Next time, we’ll finish our series on local exhaust ventilations systems by looking at the last component in the system: the exhaust stack. _____________________________________________ |

Posts Tagged ‘flammable vapor’

Industrial Ventilation – Local Exhaust Ventilation Fans

Sunday, May 22nd, 2011Industrial Ventilation – Dilution Ventilation

Sunday, April 3rd, 2011| If you’re a fan of the new hit HBO series, Boardwalk Empire, then you know a lot about the effects of Prohibition. But did you know that Prohibition is responsible for the creation of mixed drinks? Until then, people drank their liquor straight. Then along came Prohibition, mob rule, and the desire to keep the booze, including some with questionable origins, flowing. This booze didn’t taste so good, and the addition of a sugary beverage to it, that is, diluting it with soda or juice, made it a lot easier to go down. By the time Prohibition was repealed in 1933, the mixed drink had taken a firm foothold in American society.

Most adults are aware of the fact that liquor, in excess, is toxic to the body. Too much of it, and the liver, which acts as a filtration device, itself becomes toxic. When that happens, poor health will follow. The same principle applies to air within a building. If it becomes thick with toxic fumes or potentially flammable vapors, indoor air quality will suffer. But if you infuse fresh air into the environment, the toxic load is diluted, making the environment habitable and safe. This addition of fresh air is called, appropriately enough, dilution ventilation. Now, the easiest way to create a dilution ventilation system is to open a window. Trouble is there often isn’t enough natural airflow to do much good. But if you step up the effort by introducing a mechanical ventilation system, complete with blowers and ductwork, the need to crack open a window becomes obsolete. By exchanging bad air for good and introducing a continual flow of fresh air, toxicity is diluted and its effects are minimized, much like the bathtub gin of Prohibition was improved by the addition of soda. The chance of fire or explosion is reduced as well. There are however limits to what dilution ventilation can accomplish. If contaminants are highly toxic or extremely flammable, then this type of ventilation system is not going to do much good. This is a situation where extremely high air flows would be required, and this is often impractical both from a cost and comfort standpoint. Imagine having to work inside a wind tunnel? In situations like these a local exhaust ventilation system is better suited to do the job, and we’ll see how those work next week. _____________________________________________ |