|

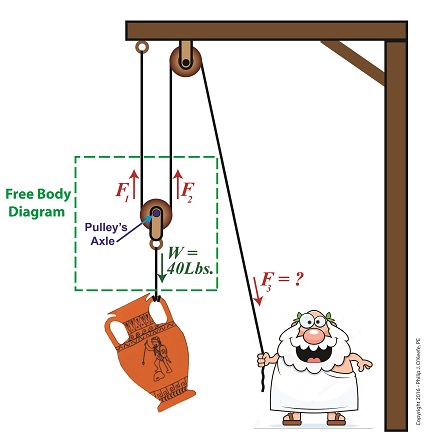

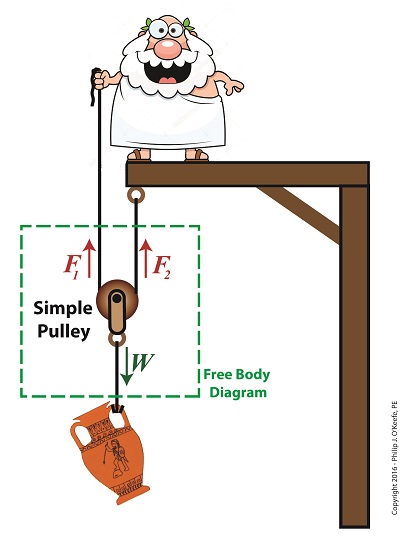

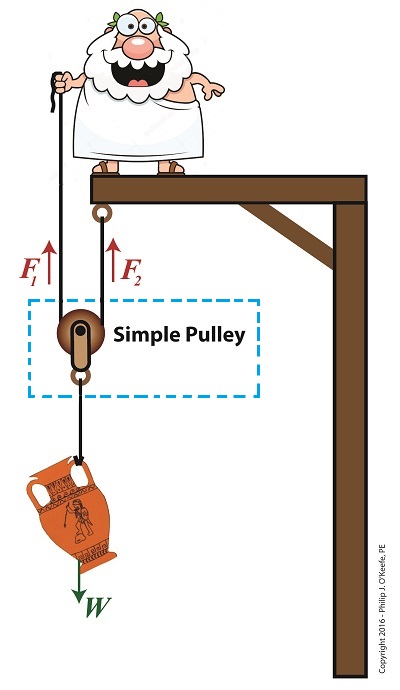

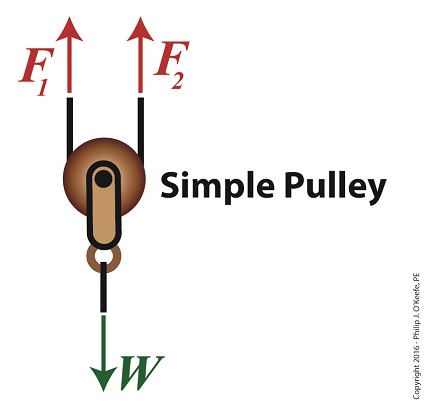

Last time we introduced the compound pulley and saw how it improved upon a simple pulley, both of which I’ve engaged in my work as an engineering expert. Today we’ll examine the math behind the compound pulley. We’ll begin with a static representation and follow up with an active one in our next blog. The compound pulley illustrated below contains three rope sections with three representative tension forces, F1, F2, and F3. Together, these three forces work to offset the weight, W, of a suspended urn weighing 40 lbs. Weight itself is a downward pulling force due to the effects of gravity. To determine how our pulley scenario affects the man holding his section of rope and exerting force F3, we must first calculate the tension forces F1 and F2. To do so, we’ll use a free body diagram, shown in the green box, to display the forces’ relationship to one another. The Math Behind a Static Compound Pulley

The free body diagram only takes into consideration the forces inside the green box, namely F1, F2, and W. For the urn to remain suspended stationary in space, we know that F1 and F2 are each equal to one half the urn’s weight, because they’re spaced equidistant from the pulley’s axle, which directly supports the weight of the urn. Mathematically this looks like, F1 = F2 = W ÷ 2 Because we know F1 and F2, we also know the value of F3, thanks to an engineering rule concerning pulleys. That is, when a single rope is used to support an object with pulleys, the tension force in each section of rope must be equal along the entire length of the rope, which means F1 = F2 = F3. This rule holds true whether the rope is threaded through one simple pulley or a complex array of fixed and moveable simple pulleys within a compound pulley. If it wasn’t true, then unequal tension along the rope sections would result in some sections being taut and others limp, which would result in a situation which would not make lifting the urn any easier and thereby defeat the purpose of using pulleys. If the urn’s weight, W, is 40 pounds, then according to the aforementioned engineering rule, F1 = F2 = F3= W ÷ 2 F1 = F2 = F3 = (40 pounds) ÷ 2 = 20 pounds Mr. Toga needs to exert a mere 20 pounds of personal effort to keep the immobile urn suspended above the ground. It’s the same effort he exerted when using the improved simple pulley in a previous blog, but this time he can do it from the comfort and safety of standing on the ground. Next time we’ll examine the math and mechanics behind an active compound pulley and see how movement affects F1 , F2 , and F3.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE Engineering Expert Witness Blog ____________________________________ |