|

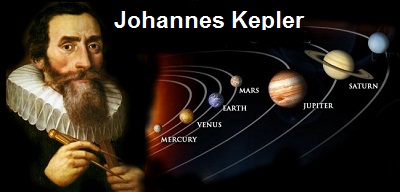

Edmund Halley was faced with a real puzzle when he began his quest to determine the distance of Earth from the sun. One of the pieces to solving that puzzle came from the work of a German mathematician, astronomer and astrologer named Johannes Kepler. Early in the 17th Century, Kepler spent a lot of time observing the planets in our solar system as they orbited the sun. He discovered that by taking note of the time it took for a planet to make one orbit around the sun, he could determine its relative distance from it. He then compared his findings with other planets, noting the time it took for each to make this same journey. His discovery would come to be known as Kepler’s Third Law of Planetary Motion. But what exactly is meant by a planet’s “relative distance from the sun”? In essence, it means that interplanetary distances, like just about everything else, are relative. Put another way, heavenly bodies can be said to be a distance X relative to another heavenly body if you establish a value for X, whether it’s numerical or otherwise. In Kepler’s case, X would be the unknown value of a so-called astronomical unit (AU), where one AU is equal to the unknown distance from Earth to the sun. Represented in equation form, this distance is: rEarth-sun = 1 AU This relative marker of distance could then be used to show how far the other planets are from the sun, relative to Earth’s distance from the sun, the AU. Kepler’s astronomical unit is simply a placeholder term for an unknown quantity, similar to any other unknown variable that might be used in an algebraic equation. For example, Kepler observed the orbits of Venus and Mars and determined their relative distances to the sun to be: rVenus-sun = 0.72 × 1 AU = 0.72 AU rMars-sun = 1.5 × 1 AU = 1.5 AU In other words, Venus’ distance from the sun is just under three quarters of Earth’s and Mars is one and a half times Earth’s distance from the sun. In this way, Kepler was able to determine the relative distances from the sun in AU for all the observable planets in our solar system. Kepler felt sure that one day scientists would be able to accurately measure Earth’s distance from the sun, and when they accomplished this they could employ his astronomical unit system to determine distances between other planets in our solar system and the sun. Next time we’ll introduce the principle of parallax and see how Halley used this optical effect to devise a method for assigning a value to Kepler’s unknown AU. ____________________________________ |

Posts Tagged ‘gravity’

Kepler’s Third Law Of Planetary Motion

Wednesday, December 31st, 2014How Far Away is the Sun?

Wednesday, December 24th, 2014|

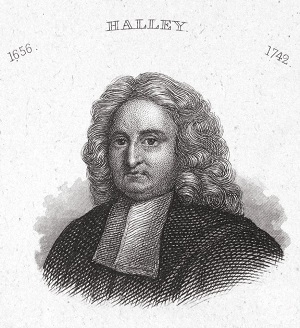

Astronomers tell us that the sun is approximately 93,000,000 miles from Earth. Since no direct method of measuring this distance exists, how did scientists determine this? They had to resort to indirect methods. In the early 18th Century, British astronomer, mathematician and physicist Edmund Halley, of Halley’s Comet fame, devised a method to measure the distance between Earth and its sun with reasonable accuracy. His method was based in part on an optical effect known as the principle of parallax, which had been discovered more than 2000 years ago by Greek astronomer Hipparchus when he also employed it to try and determine that same distance. Halley also employed the ideas of 17th Century German mathematician, astronomer, and astrologist Johannes Kepler. Kepler’s work on planetary motion, in particular the geometry of planetary orbits in our solar system, were vital to Halley’s distance measuring method. Next time we’ll see how Kepler’s Third Law of Planetary Motion brought Halley one step closer to methodology that would determine the distance of our home planet to its sun. _______________________________________

|

Gravity and the Mass of the Sun

Friday, December 12th, 2014|

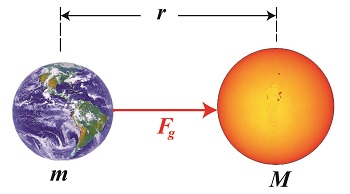

As a young school boy I found it hard to believe that scientists were able to compute the mass of our sun. After all, a galactic-sized measuring device does not exist. But where there’s a will, there’s a way, and by the 18th Century scientists had it all figured out, thanks to the work of others before them. Newton’s two formulas concerning gravity were key to later scientific discoveries, and we’ll be working with them again today to derive a third formula, bringing us a step closer to determining our sun’s mass. Newton’s Second Law of Motion allows us to compute the force of gravity, Fg, acting upon the Earth, which has a mass of m. It is, Fg = m × g (1) Newton’s Universal Law of Gravitation allows us to solve for g, the sun’s acceleration of gravity value, g = (G × M) ÷ r2 (2) where, M is the mass of the sun, r is the distance between the sun and Earth, and G is the universal gravitational constant. You will note that g is a common factor between the two equations, and we’ll use that fact to combine them. We’ll do so by substituting the right side of equation (2) for the g in equation (1) to get, Fg = m × [(G × M) ÷ r2] then, using algebra to rearrange terms, we’ll set up the combined equation to solve for M, the sun’s mass: M = (Fg × r2) ÷ (m × G) (3) At this point in the process we know some values for factors in equation (3), but not others. Thanks to Henry Cavendish’s work we know the value of m, the Earth’s mass, and G, the universal gravitational constant. What we don’t yet know is Earth’s distance to the sun, r, and the gravitational attractive force, Fg, that exists between them. Next time we’ll introduce some key scientists whose work contributed to a method for computing the distance of our planet Earth to its sun. _______________________________________

|

The Inverse Relationship of the Acceleration of Gravity

Friday, December 5th, 2014|

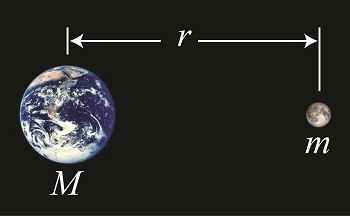

In this blog series we’ve been working our way towards determining mass values for heavenly bodies in our universe. Today we’ll explore the inverse relationship phenomenon that’s present when examining the acceleration of gravity between two heavenly bodies, for our purposes Earth and its moon. To demonstrate the inverse relationship phenomenon, we’ll use Newton’s Law of Gravitation formula: g = (G × M) ÷ r2 (1) In this formula g represents Earth’s acceleration of gravity that’s acting upon the moon. The center of the moon is located at a distance r from Earth’s center. Earth’s mass is represented by M, and G is the universal gravitational constant, which never varies from its value of 3.49 × 10-8 cubic feet per slug per second squared. We’ll solve for Earth’s g factor relative to the moon, which we’ll position at varying distances from Earth’s core, thereby demonstrating how the attracting force of Earth’s gravity becomes weaker as the moon’s distance from Earth’s core increases — hence the inverse relationship. To begin, we know that the present distance from Earth’s center to the center of the moon is about 238,900 miles, or 1,261,392,000 feet. We also know that Earth’s mass, M, is equal to 4.09 × 1023 slugs. Plugging these values into Newton’s Law of Gravitation equation, we calculate the acceleration of gravity exerted upon the moon in this, its normal orbit, to be: g = ((3.49 × 10-8 ft3/slug/sec2) × (4.09 × 1023 slugs)) ÷ (1,261,392,000 ft)2 g = 0.0089 ft/sec2 Now let’s suppose that the moon’s orbit was caused to increase so that it became situated 400,000 miles, or 2,112,000,000 feet from Earth. Earth’s acceleration of gravity exerted upon the moon at this distance would be calculated as: g = ((3.49 × 10-8 ft3/slug/sec2) × (4.09 × 1023 slugs)) ÷ (2,112,000,000 ft)2 g = 0.0032 ft/sec2 From these two examples we can see that the further the moon is positioned from Earth, the weaker Earth’s gravitational pull upon it is. This gravitational pull is the force of gravity, Fg, introduced in our last blog, a term which originates in Newton’s Second Law of Motion, as given by the equation: Fg = m × g (2) where, in this case, m represents the mass of the moon. Next time we’ll combine equations (1) and (2) and derive a third formula which will allow us to calculate the mass of the sun.

_______________________________________

|

The Force of Gravity

Thursday, November 20th, 2014|

Last time we saw how Henry Cavendish built upon the work of scientists before him to calculate Earth’s mass and its acceleration of gravity factor, as well as the universal gravitational constant. These values, together with the force of gravity value, Fg, which we’ll introduce today, moved scientists one step further towards being able to discover the mass and gravity of any heavenly body in the universe. According to Newton’s Second Law of Motion, the force of gravity, Fg, acting upon any object is equal to the object’s mass, m, times the acceleration of gravity factor, g, or, Fg = m × g So what is Fg? It’s a force at play way up there, in the outer reaches of the galaxy, as well as back home. It keeps the moon in orbit around the Earth and the Earth orbiting around the sun. In the same way, Fg keeps us anchored to Earth, and if we were to calculate it, it would be calculated as the force of our body’s mass under the influence of Earth’s gravity. It’s common to refer to this force as weight, but it’s not quite so simple. Using the metric system, the unit of measurement most often used for scientific analyses, weight is determined by multiplying our body’s mass in kilograms by the Earth’s acceleration of gravity factor of 9.8 meters per second per second, or 9.8 meters per second squared. For example, suppose your mass is 100 kilograms. Your weight on Earth would be: Weight = Fg = m × g = (100 kg) × (9.8 m/sec2) = 980 kg · m/sec2 = 980 Newtons Newtons? That’s right. It’s easier than saying kilogram · meter per second per second. It’s also a way to pay homage to the man himself. In the English system of measurement things are perhaps even more confusing. Your weight is found by multiplying the mass of your body measured in slugs by the Earth’s acceleration of gravity factor of 32 feet per second per second. Slugs is British English speak for pounds · second squared per foot. We normally refer to weight in units of pounds, and in engineering circles it’s pounds force. For example, suppose your mass is 6 slugs, or 6 pounds · second squared per foot. Your weight on Earth would be: Weight = Fg = m × g = (6 Lbs · sec2/ft) × (32.2 ft/sec2)= 193.2 Lbs To avoid any confusion, you could just step on the bathroom scale. Next time we’ll see how the force of gravity is influenced by an inverse proportionality phenomenon. _______________________________________

|

What is Earth’s Mass?

Friday, November 7th, 2014|

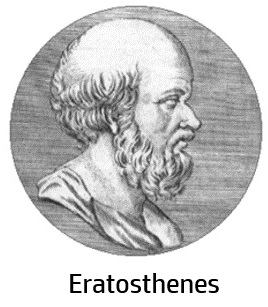

Last time we learned how Henry Cavendish used Christiaan Huygens’ work with pendulums to determine the value of g, the acceleration of gravity factor for Earth, to be 32.3 ft/sec2, or 9.8 m/sec2. From there Cavendish was able to go on and arrive at values for other factors in Isaac Newton’s gravity formula, namely G, the universal gravitational constant, and M, Earth’s mass. Today, we’ll discuss how Cavendish was able to calculate the Earth’s mass. Newton’s formula for gravity, once again, is: M = (g × R2) ÷ G where M stands for the mass of the heavenly body being quantified. For our case today M will represent the mass of Earth, which was originally quantified in slugs, a British unit of measurement. Today the measurement unit of choice in most parts of the world is the kilogram, which is the metric equivalent of a slug. With regard to the other variables in Newton’s gravity formula, namely, R and G, their values had previously been determined. Eratosthenes’ measurement of shadows cast by the sun on Earth’s surface had revealed Earth’s radius, R, to be 6,371 kilometers, or 6,371,000 meters. And Cavendish’s experiments led him to conclude that the universal gravitational constant, G, was 6.67 × 10-11 cubic meters per kilogram-second squared. Plugging these values into Newton’s equation, we calculate Earth’s mass to be: M = ((9.8 m/sec2) × (6,371,000 m)2) ÷ (6.67 × 10-11 m3/kg-sec2) M = 5.96 × 1024 kilograms Incidentally, 5.96 × 1024 is scientific notation, or mathematical shorthand, for the number 5,960,000,000,000,000,000,000,000. That’s a whole lot of zeros! Calculating the mass of Earth was an impressive accomplishment. Now that its value was known, scientists would be able to calculate the mass and acceleration of gravity for any heavenly body in the universe. We’ll see how that’s done next time.

_______________________________________

|

Huygens’ Use of Pendulums

Tuesday, October 21st, 2014|

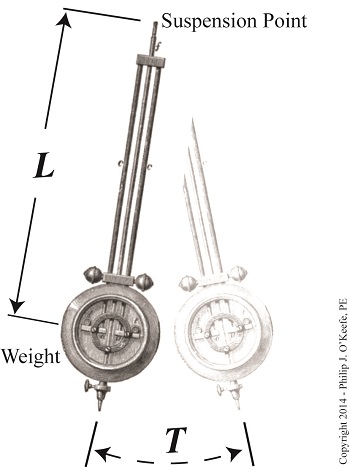

Last time we learned that Henry Cavendish determined a value for G, the universal gravitational constant, fast on his way to determining a quantity he was determined to find, the Earth’s mass. Today we’ll see how the previous work of Christiaan Huygens, a contemporary of Isaac Newton’s, helped him get there. First Cavendish used algebra to rearrange terms in Newton’s gravitational formula so as to solve for M, Earth’s mass. Rearranged, Newton’s formula becomes, M = (g × R2) ÷ G But in order to solve for M, Cavendish first needed to know Earth’s acceleration of gravity, g. To aid him in this calculation he referred back to the work of Christiaan Huygens, a Dutch mathematician from Newton’s time. Huygens was eager to devise a formula capable of predicting clock pendulums’ motions on ships, his goal being to invent a timepiece accurate enough to make navigating ships easier. He hypothesized that a key factor in predicting a pendulum’s movement was an unknown constant, the acceleration of gravity factor, g, which Newton had previously posited existed. Through meticulous observation, Huygens came to realize that the time it took for pendulums to complete one swing back and forth was dependent not only on the length of the pendulum, but also this unknown quantity. In order for Huygens’ computations to work, the value of g had to be a constant, meaning, its value could not vary between computations; g‘s value was in fact a fudge factor, a phantom he would assign a specific numerical value. Huygens’ needed it in order to make his hypothesis work, a practice commonly use by scientists, even today. Determining a value for g would allow Huygens to successfully relate the length of the pendulum to the timing of its swing and to create a mathematical relationship between them. Huygens ultimately determined g’s value to be a whopping 32.2 feet per second per second, or 32.2 ft/sec2. We’ll see how he did it next time.

_______________________________________

|

How Big is the Earth?

Wednesday, October 8th, 2014|

Last time we discussed Isaac Newton’s Law of Gravitation and how he used it to arrive at conclusions concerning gravity. He theorized the existence of a universal gravitational constant, G, a set numerical value for all heavenly bodies in our universe, and he developed a formula to determine the acceleration of gravity, g. Newton felt sure that the gravity at play on the surface of any heavenly body, such as stars and planets, could be determined if one knew the value of G, along with the object’s mass, M, and radius, R, and he developed this equation to do so, g = (G × M) ÷ R2 At this point you may be thinking, Finding the mass and radius of a heavenly body is hard enough, but what is this universal gravitational constant?? Good point. Back in Newton’s time, the existence of G was purely speculative. He conceived it to be a numerical value which would act as a fudge factor, enabling his equation for determining g to work. As a matter of fact, Newton had no clue of how to determine G and was convinced that it would be beyond anyone’s ability to do so. The mysterious G factor and its numerical value were not actually determined until more than a hundred years later by Henry Cavendish. In 1796 Cavendish was focused on determining the Earth’s mass, M, by using Newton’s equation. To arrive at a value for G, Cavendish conducted experiments which measured the gravitational attraction between two lead spheres attached by way of a torsion balance. After much testing he eventually concluded that he had computed G to a reasonable degree of accuracy and that its value was equal to 3.439 x 10-8 cubic feet per slug per second squared. In this case a slug is not a slimy creature living in the garden, but rather a unit of measurement used to quantify the mass of an object. For the full story, see this article on Cavendish’s experiment by The Physics Classroom. But even after determining G, Cavendish still had to obtain values for g and R in order to calculate M. This was made possible thanks to the work of two men who came before him. One of these was the Greek mathematician Eratosthenes, who way back in 230 B.C. discovered that the radius of the earth, R, could be calculated by simply measuring the shadows of objects cast on Earth’s surface. All he needed was a measuring stick and geometry. For the full story see this fascinating article on the subject from Bucknell University. As for the value of g, the acceleration of gravity on Earth, Cavendish was aided by the previous efforts of a Dutch mathematician from Newton’s time, Christiaan Huygens. You may recall that Huygens was first introduced in a previous blog series on spur gear geometry, where we learned that he studied the motion of clock pendulums. Through observation, Huygens was able to arrive at a mathematical formula capable of predicting the pendulums’ often erratic motion on ships at sea. Next time we’ll see how Huygens’ insights gained by watching pendulums ultimately made it possible for him to arrive at a numerical value for Earth’s acceleration of gravity, g. _______________________________________

|

Sir Isaac Newton and the Acceleration of Gravity

Thursday, September 18th, 2014|

Last time we watched a video of Astronauts Scott and Irwin simultaneously dropping a hammer and feather to the surface of the Moon and were amazed to find that the objects struck the surface at exactly the same time. It was history in the making, and Galileo’s theory regarding gravity was proven beyond a shadow of a doubt. If you watched the video of the event very closely, it might have struck you that the hammer was falling more slowly than it would had it been dropped on Earth, and you’d be right. Let’s find out why. Sir Isaac Newton was a pioneer in this subject matter. According to his book, Philosophia Naturalis Principia Mathematica, first published in 1687, every heavenly body in the universe, whether it be planet, moon, or star, generates gravity, and any object in freefall towards its surface will be subject to that gravity. He posited that the falling object will gain speed at a constant rate as it falls, that constant speed being dictated by the acceleration of gravity factor that’s at play on the heavenly body it’s falling toward. For example, if the acceleration due to gravity on a small planet is, say, 2 feet per second per second, after one second of falling, an object’s velocity will be 2 feet per second. After two seconds of falling, the object will have accelerated to a velocity of 4 feet per second. After three seconds, the object’s velocity will have accelerated to 6 feet per second, and so on. In other words, the speed, or velocity, of the object’s descent will increase for every second it falls closer to the surface of the planet, a phenomenon which is measured in units of feet per second (ft/sec). The acceleration of gravity of a falling object is the linear increase in its velocity that takes place during each succeeding second of its fall, a phenomenon which is measured in feet per second per second (ft/sec2). Next time we’ll discuss the formula which enables us to calculate gravitational acceleration. We have Sir Isaac to thank for that one, too. _______________________________________

|