|

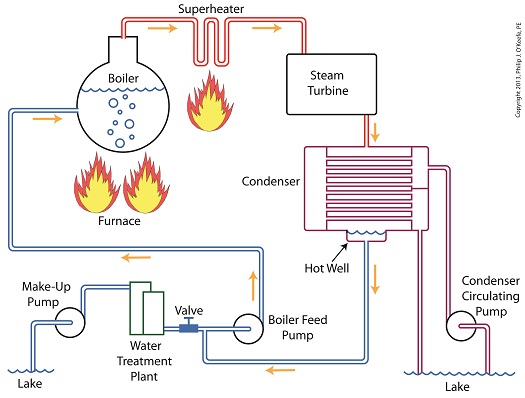

Last time we learned how the condenser within a power plant acts as a conservationist by transforming steam from the turbine exhaust back into water. This previously purified water, or condensate, contains valuable residual heat energy from its earlier journey through the power plant, making it perfect for reuse within the boiler, resulting in both water and fuel savings for the plant. Today we’ll take a look at a highly pressurized form of condensate known as boiler feed water and how it helps the power plant save money by recycling residual heat energy in the steam and water cycle. Let’s begin by integrating the condenser into the big picture, the complete water-to-steam power plant cycle, to see how it fits in. The illustration shows that both the make-up pump and the condenser circulating water pump draw water from the same supply source, in this case a lake. The circulating water pump continuously draws in water to keep the condenser tubes cool, while the make-up pump draws in water only when necessary, such as when initially filling the boiler or to make up for leaks during operation, leaks which typically occur due to worn operating parts. In a nutshell, the condenser recycles steam from the turbine exhaust for its reuse within the power plant. The journey begins when condensate drains from the hot well located at the bottom of the condenser, then gets siphoned into the boiler feed pump. If you recall from a previous article, the boiler feed pump is a powerful pump that delivers water to the boiler at high pressures, typically more than 1,500 pounds per square inch in modern power plants. After its pressure has been raised by the pump, the condensate is known as boiler feed water. The boiler feed water leaves the boiler feed pump and enters the boiler, where it will once again be transformed into steam, and the water-to-steam cycle starts all over again. That is, boiler feed water is turned to steam, it’s superheated to drive the turbine, then condenses back into condensate, and finally it’s returned to the boiler again by the boiler feed pump. Trace its journey along this closed loop by following the yellow arrows in the illustration. While you were following the arrows you may have noticed a new valve in the illustration. It’s on the pipe leading from the water treatment plant to the boiler feed pump. Next time we’ll see how this small but important item comes into play in the operation of our basic power plant steam and water cycle. ________________________________________ |

Posts Tagged ‘lake water’

Boiler Feed Water, A Special Kind of Condensate

Tuesday, October 22nd, 2013How A Power Plant Condenser Works, Part 2

Sunday, October 6th, 2013|

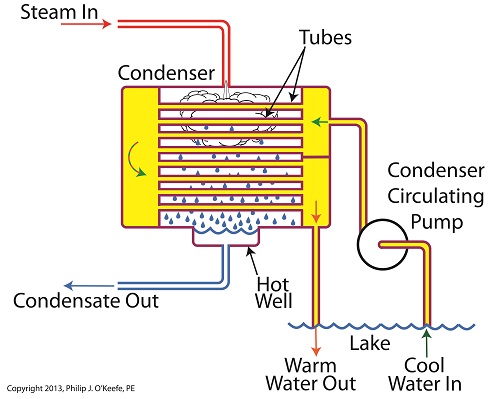

Winter is fast approaching. Imagine living in a house without insulation. Now imagine your heating bill, which will be high due to the tremendous amount of heat loss. Energy is a precious resource, no matter how it’s produced, and its conservation within a power plant’s steam/water cycle is of vital importance. Last time we learned about the transfer of heat energy within a power plant’s condenser, where some of the heat energy contained within its steam is absorbed by the cool lake water contained inside its tubes. Steam is continuously flowing into the condenser from the steam turbine, so it’s essential for the circulating pump to keep a fresh supply of lake water flowing through the condenser’s tubes in an effort to keep temperatures under control. The compensating action that’s provided by the cool lake water flowing within the tubes, represented by green arrows in the illustration, keeps the temperature inside the tubes from rising and becoming equal to the steam’s temperature outside of them. If the flow of cool water through the tubes were to stop and the temperatures inside and outside the tubes become equal, the water contained inside the tubes would boil off to steam, resulting in the tubes bursting and a wrecked condenser. After absorbing heat energy from the surrounding steam, the warmed lake water within the tubes follows a circuitous path through the tubing, eventually emptying out into the lake. The orange arrows in the illustration show this path. Okay, with this warm water entering the lake, doesn’t that harm the eco system? Actually its impact is negligible. You see, the temperature of the lake water leaving the condenser is only about 10°F higher than when it was pumped from the lake. Add this to the fact that the volume of water contained within a lake is huge in comparison to the small amount of warmed water being returned to it. Next week we’ll see how the loss of heat energy affects the steam, and how an important part of the condenser known as the hot well comes into play. ________________________________________ |

How A Power Plant Condenser Works, Part 1

Wednesday, October 2nd, 2013|

Last time we began our discussion on power plant inefficiencies and indentified a major contributor, the heat energy dispelled into the atmosphere through the turbine exhaust. Today we’ll see how a piece of equipment known as the condenser comes into play to deal with this problem. Let’s see how it works. First, water from our plant’s water source, say a nearby lake, is siphoned into the condenser circulating pump, which delivers it to the condenser. This lake water path appears in yellow. You’ll notice that the lake water follows a circuitous path from the lake, through the condenser circulating pump, then the condenser tubes, until finally it is returned to the lake. Now the cool lake water, denoted by green arrows, is made to pass through the condenser’s many tubes, while steam from the turbine exhaust surrounds them. The tubes keep the lake water segregated from the cloud of steam surrounding them inside the condenser vessel. In other words, the lake water’s path is a closed system, never coming into direct physical contact with the surrounding steam. What’s happening inside our condenser is demonstrative of a fundamental principle of thermal engineering, that is, that hot will travel in the direction of cold. More specifically, within our condenser the heat energy in the steam cloud surrounding the condenser tubes will be attracted to the cool lake water contained within the tubes. This causes the heat energy contained within the steam to leave it, and get absorbed by the cool lake water flowing within the tubes. We’ll begin to find out how these dynamics influence what’s happening with our water-to-steam power plant cycle next time.

________________________________________ |