| When I was a child in school I loved field trips. They didn’t happen too often, but when they did they were a welcomed break from the routine of the classroom. Once we went on a tour of a large factory that made telephones. During the tour we walked amongst gargantuan machines, conveyor belts, furnaces, boilers, pumps, and compressors, all energized and working together to transform raw materials into telephones. Sequences of manufacturing and assembly operations, from the simple to the most complex, were carefully orchestrated with no apparent human intervention.

The equipment in the telephone factory was certainly impressive to watch, and our tour guides did a fine job of explaining what was happening, except for one important detail. I realized after we left that no one had explained who or what was actually controlling the machinery. I realized even then that machines can’t think for themselves. They can only do what humans tell them to do. I didn’t know it at the time, but the telephone factory setup included some interesting examples of industrial control systems. Industrial control systems can be broken down into two basic categories, manual controls and automatic controls. Manual controls work as their name implies, that is, someone must manually press a button or throw a switch to initiate factory operations. This involves continual monitoring of processes, coupled with hands-on activities to keep everything working. Automatic controls still require human intervention to some extent, such as initiating operations, but once that’s done they move into self-regulation mode until the operations are shut down at the end of production. Employees are thus freed up to spend time doing things which are not automated. Automatic controls are excellent at handling mundane, repetitive tasks that humans tend to get quickly bored with. Boredom leads to a lack of attention, and this may lead to accidents, so utilizing automatic controls often makes for a safer work environment. Next time we’ll begin our examination of how manual and automatic controls work within the context of an industrial setting. To begin, we’re going to take a virtual field trip back to the telephone factory and look at some basic industrial control examples. ____________________________________________

|

Posts Tagged ‘machines’

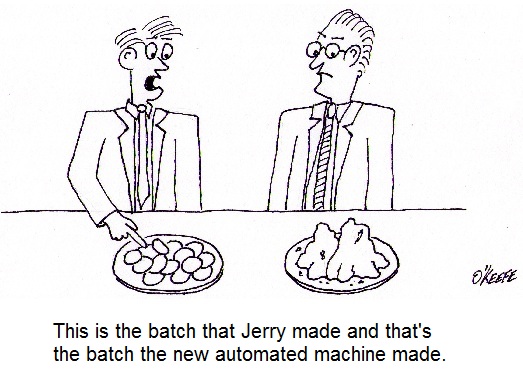

Food Manufacturing Challenges – Look and Taste

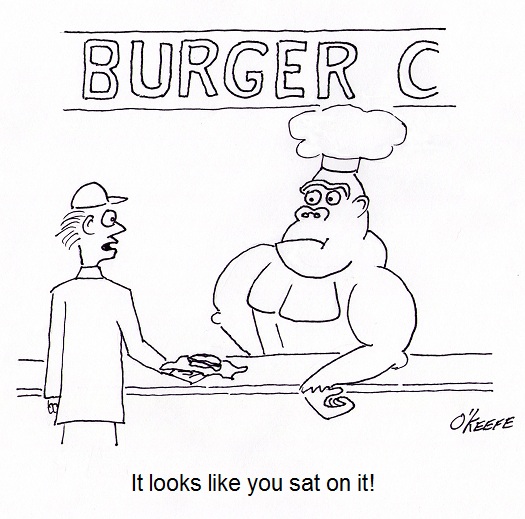

Sunday, September 25th, 2011| Ever wonder why the burger you get at your favorite fast food chain never looks like the one on TV? The bun isn’t fluffy, the beef patty doesn’t make it to the edges, and the lettuce is anything but crisp. Well, it’s because a professional known as a Food Stylist, working together with a professional marketing firm and production crew, has painstakingly created the beautiful, bright and balanced burger used to lure you in. The process can take days or even weeks to create and has nothing to do with reality. The burger you’re really going to get will look more like a gorilla sat on it.

Many of the same issues must be dealt with when mass producing food. Chances are human hands will never even touch the product, like they did when creating the prototype in the test kitchen. In the world of food manufacturing, the “look” part can be extremely challenging. How do you get machines and production lines to create visually appealing food that entices prospective buyers to make an investment in it? How do you get it to taste good, or at least acceptable to the palate? The “taste” part of food manufacturing can be even more challenging. For example, in the test kitchen of a pastry product manufacturer, a recipe will be developed using home pantry products like flour, butter, and eggs. Ever made bread or a pie crust? The stickiness factor is enough to drive many insane. Even nimble human fingers have a hard time dealing with it. Now enter food processing machinery and conveyor belts into the scenario. This brings the possibility of stickiness to a whole new level. Huge messes that gum up the machinery are common, and production line shutdowns are the result. When faced with these challenges, plant engineers have to work closely with chefs in the R&D kitchen to come up with some sort of compromise in the recipe or final form of the food product. The goal is to cost effectively produce food products acceptable to consumers for purchase, and it’s often an iterative process involving many successive changes to recipes and equipment designs, coupled with a lot of testing and retesting, before success is finally met. If testing ultimately proves that the product appeals to consumers’ tastes and flows nicely through production lines, then there’s a good chance it will be a commercial success. In any case, cost is the dictating factor as to whether the food product will successfully make it onto the shelves of your supermarket. A margin of profit must be made. But this success is only part of the design process. Before full commercial production can commence, processing equipment and production lines must be designed so that they:

Next time we’ll explore how cleanliness requirements factor into food manufacturing equipment design. ____________________________________________ |