| Electric motors are everywhere, from driving the conveyor belts, tools, and machines found in factories, to putting our household appliances in motion. The first electric motors appeared in the 1820s. They were little more than lab experiments and curiosities then, as their useful potential had not yet been discovered. The first commercially successful electric motors didn’t appear until the early 1870s, and they could be found driving industrial devices such as pumps, blowers, and conveyor belts.

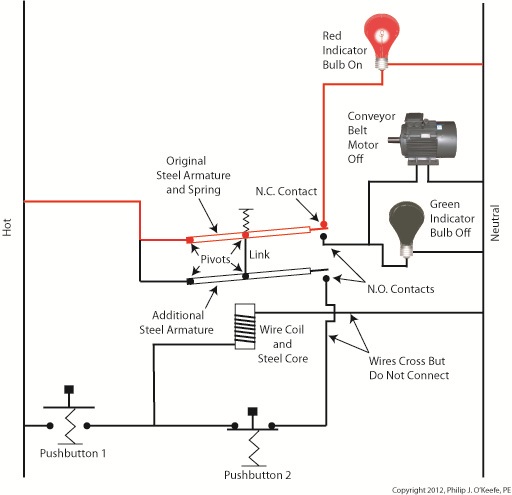

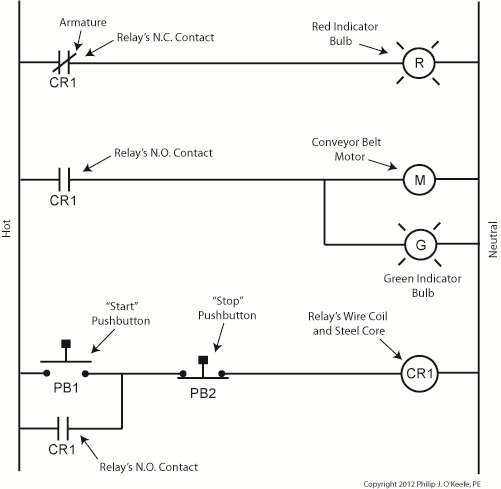

In our last blog we learned how a latched electric relay was unlatched at the push of a button, using red and green light bulbs to illustrate the control circuit. Now let’s see in Figure 1 how that circuit can be modified to include the control of an electric motor that drives, say, a conveyor belt inside a factory. Figure 1

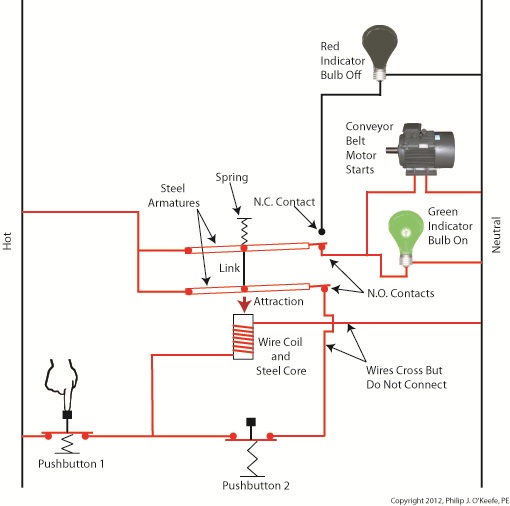

Again, red lines in the diagram indicate parts of the circuit where electrical current is flowing. The relay is in its normal state, as discussed in a previous article, so the N.O. contacts are open and the N.C. contact is closed. No electric current can flow through the conveyor motor in this state, so it isn’t operating. Our green indicator bulb also does not operate because it is part of this circuit. However current does flow through the red indicator bulb via the closed N.C. contact, causing the red bulb to light. The red and green bulbs are particularly useful as indicators of the action taking place in the electric relay circuit. They’re located in the conveyor control panel along with Buttons 1 and 2, and together they keep the conveyor belt operator informed as to what’s taking place on the line, such as, is the belt running or stopped? When the red bulb is lit the operator can tell at a glance that the conveyor is stopped. When the green bulb is lit the conveyor is running. So why not just take a look at the belt itself to see what’s happening? Sometimes that just isn’t possible. Control panels are often located in central control rooms within large factories, which makes it more efficient for operators to monitor and control all operating equipment from one place. When this is the case, the bulbs act as beacons of the activity taking place on the line. Now, let’s go to Figure 2 to see what happens when Button 1 is pushed. Figure 2

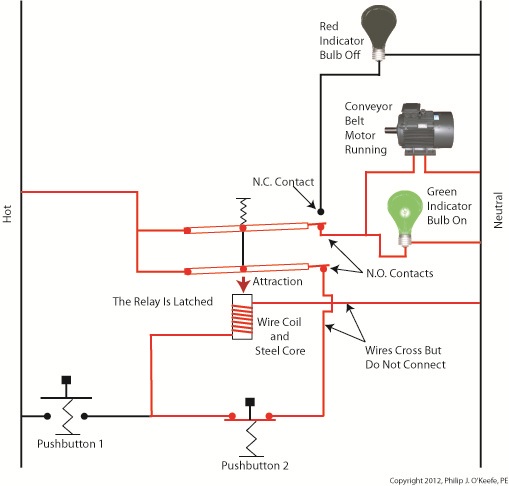

The relay’s wire coil becomes energized, causing the relay armatures to move. The N.C. contact opens and the N.O. contacts close, making the red indicator bulb go dark, the green indicator bulb to light, and the conveyor belt motor to start. With these conditions in place the conveyor belt starts up. Now, let’s look at Figure 3 to see what happens when we release Button 1. Figure 3

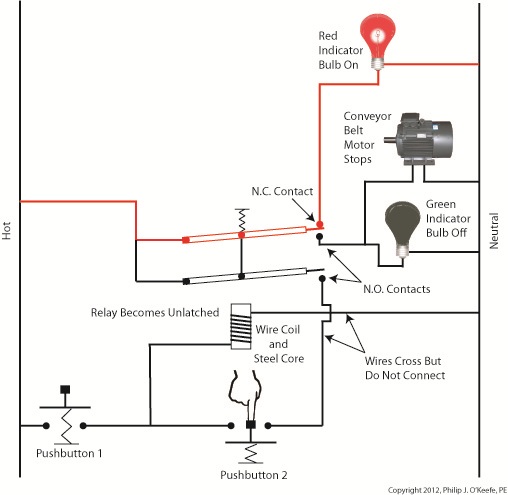

With Button 1 released the relay is said to be “latched” because current will continue to flow through the wire coil via one of the closed N.O. contacts. In this condition the red bulb remains unlit, the green bulb lit, and the conveyor motor continues to run without further human interaction. Now, let’s go to Figure 4 to see how we can stop the motor. Figure 4

When Button 2 is depressed current flow through the relay coil interrupted. The relay is said to be unlatched and it returns to its normal state where both N.O. contacts are open. With these conditions in place the conveyor motor stops, and the green indicator bulb goes dark, while the N.C. contact closes and the red indicator bulb lights. Since the relay is unlatched and current no longer flows through its wire coil, the motor remains stopped even after releasing Button 2. At this point we have a return to the conditions first presented in Figure 1. The ladder diagram shown in Figure 5 represents this circuit. Figure 5

Next time we’ll introduce safety elements to our circuit by introducing emergency buttons and motor overload switches. ____________________________________________ |

Posts Tagged ‘N.C.’

Industrial Control Basics – Electric Motor Control

Sunday, February 19th, 2012Tags: blower, closed contact, control panel, control room, conveyor belt, electric current flow, electric motor, electric relay, engineering expert witness, equipment operator, factory, forensic engineer, indicator lamp, industrial control, ladder diagram, latched circuit, motor control, motor drive, N.C., N.O., normal state, normally closed, normally open, panel indicator, pump, push button, safety, start pushbutton, stop pushbutton

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability, Professional Malpractice | Comments Off on Industrial Control Basics – Electric Motor Control

Industrial Control Basics – Electric Relay Operation

Monday, January 9th, 2012| It’s a dark and stormy night and you’ve come to the proverbial fork in the road. The plot is about to take a twist as you’re forced to make a decision in this either/or scenario. As we’ll see in this article, an electric relay operates in much the same manner, although choices will be made in a forced mechanical environment, not a cerebral one.

When we discussed basic electric relays last week we talked about their resting in a so-called “normal state,” so designated by industrial control parlance. It’s the state in which no electric current is flowing through its wire coil, the coil being one of the major devices within a relay assembly. Using Figure 3 of my previous article as a general reference, in this normal state a relaxed spring keeps the armature touching the N.C. switch contact. While in this state, a continuous conductive path is created for electricity through to the N.C. point. It originates from the wire on the left side, which leads to the armature pivot point, travels through the armature and N.C. contact points, and finally dispenses through the wire at the right leading from the N.C. contact. Now let’s look at an alternate scenario, when current is made to flow through the coil. See Figure l, below. Figure 1Figure 1 shows the path of electric current as it flows through the wire coil, causing the coil and the steel core to which it’s attached to become magnetized. This magnetization is strong, attracting the steel armature and pulling it towards the steel core, thus overcoming the spring’s tension and its natural tendency to rest in a tension-free state. The magnetic attraction causes the armature to rotate about the pivot point until it comes to rest against the N.O. contact, thus creating an electrical path en route to the N.O. wire, on its way to whatever device it’s meant to energize. As long as current flows through the wire coil, its electromagnetic nature will attract the armature to it and contact will be maintained with the N.O. juncture. When current is made to flow through the wire coil, an air gap is created between the armature and the N.C. contact, and this prevents the flow of electric current through the N.C. contact area. Current is forced to follow the path to the N.O. contact only, effectively cutting off any other choice or fork in the road as to electrical path that may be followed. We can see that the main task of an electric relay is to switch current between two possible paths within a circuit, thereby directing its flow to one or the other. Next time we’ll examine a simple industrial control system and see how an electric relay can be engaged with the help of a pushbutton. ____________________________________________ |

Tags: armature, coil, control relay, control system, current flow, electric current, electric relay, electrical path, electrical relay, electrical switch, electricity, electromagnetic, engineering expert witness, forensic engineering, industrial control, magnetic attraction, N.C., N.C. contact, N.O., N.O. contact, normal state, normally closed, normally open, pushbutton, relay, relay ladder logic, spring, steel core, switch, switch contact, switching current, wire coil

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability, Professional Malpractice | 1 Comment »