|

Last time I introduced the concept of intellectual property, or IP. We learned that IP in the eyes of the law is recognized as a creation of an individual inventor’s mind, worthy of commercial value. It goes to follow that those inventions that have been awarded patents are also a form of IP, because they represent the working ideation of the inventor’s mind. As such, the patent grants the inventor the sole legal right to profit from the invention to the exclusion of all others. So all you need is an idea, and you can apply for a patent, right? Well, not really. There are in fact a number of tests that potentially patentable inventions must pass. Federal laws governing patents have been in existence since 1790. They were put in place to give inventors the means to legally protect their exclusive rights to profit from their inventions in our new country. The first patent was awarded to inventor Samuel Hopkins on July 31st of that year, for a process he created to make potash, an ingredient used to make fertilizer. Since that time, the patent laws have been continually revised and expanded to improve the patenting process, something that became necessary due to the explosion of patentable technological innovations after the Industrial Revolution started in the 19th Century. In July of 1952, the basic structure of modern patent law was laid out by Title 35 of the United States Code (USC). Title 35 is a set of laws drafted by Congress that contains all federal statutes governing patents. Within Title 35 is found Section 101. It’s the part that addresses patent eligibility. This Section is commonly referred to within the trade by patent agents and attorneys as 35 USC § 101, shorthand for “Title 35 of the USC, Section 101.” According to 35 USC § 101, in order to be patentable an invention must first be useful. In addition, it must be either a machine, an article of manufacture, a composition of matter, or a process, or it must improve upon an existing machine, article of manufacture, composition, or process. But what does this all really mean? We’ll find out next time. ___________________________________________ |

Posts Tagged ‘intellectual property’

Determining Patent Eligibility – Part 1

Sunday, April 7th, 2013Patents, Defined

Sunday, March 31st, 2013|

While pursuing my engineering degree my professors provided me with a thorough understanding of mechanical and electrical design and instruction on how to build prototypes for testing. As far as technical skills were concerned, I was well equipped to turn my ideas into real inventions. Unfortunately, my engineering school, like most others, never went beyond these technical aspects of inventing. For example, we never discussed the business and legal aspects of manufacturing and selling an invention. The fact is, most first time inventors have little or no understanding of how to go about obtaining a patent to prevent others from copying and profiting from their inventions. They also tend to take a haphazard approach to inventing, neglecting important issues such as whether a market for their invention exists, or whether they will face competition already in place. A lot of time and money can be spent developing an invention, only to discover that it had already been patented by someone else. They do all the up-front work, blissfully unaware of the repercussions of negative possibilities, like getting sued by any existing patent holder, suits which are among the most expensive to defend. For most individuals the patent process is a hotbed of mysteries and misconceptions. Let’s start unraveling them by first gaining a basic understanding of what a patent is. In short, a patent grants you a legal right, much like other legal rights you may be more familiar with. For example, if you own property, say a car or piece of real estate, you’re provided with a legal document known as a title. This title defines your legal right to own that property. Similar to a title, a patent grants you the legal right to own intellectual property, or IP, as its inventor. IP is a term used in the business and legal arenas to refer to creations of the inventor’s mind. Once patented, these creations become the property of the inventor, and they have commercial value. This value is derived from the fact that the patent can be used to exclude others from producing the invention and profiting from it. The IP rights can also be sold or licensed to others for a profit. IP can encompass subjects as diverse as machinery, articles of manufacture, compositions of matter, and many diverse processes, all of which we’ll look into during the course of this blog series. ___________________________________________ |

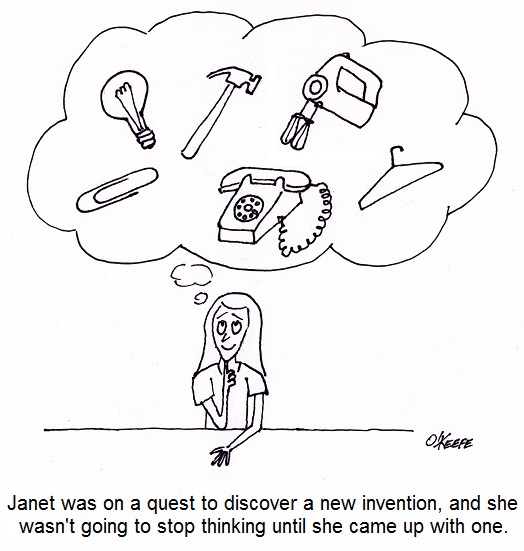

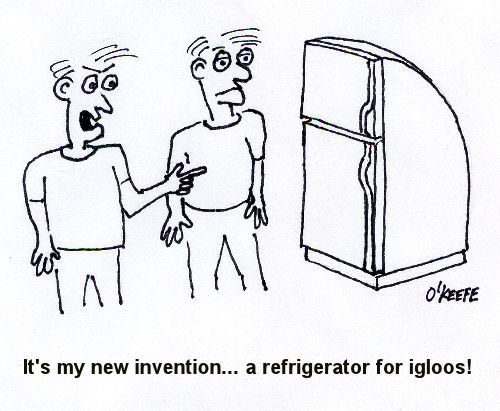

You Can Make It, But They May Not Buy It

Sunday, August 9th, 2009|

When Thomas A. Edison was a young man in the late 1860s, he made the same mistake that many of today’s novice inventors make: he concentrated all of his efforts on developing and patenting an invention without first doing a thorough market study to see if it had a good chance of being a commercial success. Edison’s first patented invention was a legislative vote recorder (US Patent No. 90,646). The device was surprisingly innovative, enabling legislators to cast their votes in record time. It made the entire voting process far more efficient than the system of roll call voting that was employed at the time. Edison had no doubt that it would be a commercial success. Who in their right mind wouldn’t want something that was efficient and saved time? Pumped full of optimism, Edison took the embodiment of his invention to Washington, D.C. to demonstrate it before a congressional committee. He was shocked to find that no one on the committee was impressed with what he’d done. And to add insult to injury, the Chairman of the committee could not resist saying, “If there is any invention on Earth that we don’t want down here, that is it.” Swallowing his pride, Edison was forced to abandon his invention. If Edison had taken the time to study the market prior to proceeding with his invention, he would have discovered that it would be a foolish waste of time and money to pursue development of the vote recorder past the preliminary concept phase. But the political process was not something he was familiar with, much less the slow pace of roll call voting that Congress employed. He was unaware that this political maneuvering enabled politicians to easily filibuster bills and make deals behind the scenes in order to sway votes. He would find out too late that his was a notion they did not care to support. After his vote recorder demonstration crashed and burned, Edison vowed to only work on inventions that people actually wanted to buy. He ultimately created the world’s first industrial research laboratory that pumped out thousands of inventions that made him a millionaire and created a technological legacy that remains with us today. _________________________________________________________________ |