|

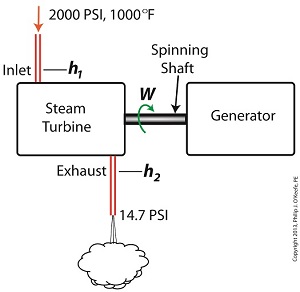

Last time we learned that the amount of useful work, W, that a steam turbine performs is calculated by taking the difference between the enthalpy of the steam entering and then leaving the turbine. And in an earlier blog we learned that a vacuum is created in the condenser when condensate is formed. This vacuum acts to lower the pressure of turbine exhaust, and in so doing also lowers the enthalpy of the exhaust steam. Putting these facts together we are able to generate data which demonstrates how the condenser increases the amount of work produced by the turbine. To better gauge the effects of a condenser, let’s look at the differences between its being present and not present. Let’s first take a look at how much work is produced by a steam turbine without a condenser. The steam entering the turbine inlet has a pressure of 2000 pounds per square inch (PSI) and a temperature of 1000°F. Knowing these turbine inlet conditions, we can go to the steam tables in any thermodynamics book to find the enthalpy, h1. Titles such as Fundamentals of Classical Thermodynamics by Gordon J. Van Wylen and Richard E. Sonntag list enthalpy values over a wide range of temperatures and pressures. For our example this volume tells us that, h1 = 1474 BTU/lb where BTU stands for British Thermal Units, a unit of measurement used to quantify the energy contained within steam or water, in our case the water to steam cycle inside a power plant. Technically speaking, a BTU is the amount of heat energy required to raise the temperature of one pound of water by one degree Fahrenheit. The term lb should be a familiar one, it’s the standard abbreviation used for pound, so enthalpy is the measurement of the amount of energy per pound of steam flowing through, in this case, the turbine. Since there is no condenser attached to the steam turbine’s exhaust in our illustration, the turbine discharges its spent steam into the surrounding atmosphere. The atmosphere in our scenario exists at 14.7 PSI because our power plant happens to be at sea level. Knowing these facts, the steam tables inform us that the value of the exhausted steam’s enthalpy, h2, is: h2 = 1015 BTU/lb Combining the two equations we are able to calculate the useful work the turbine is able to perform as: W = h1 – h2 = 1474 BTU/lb – 1015 BTU/lb = 459 BTU/lb This equation tells us that for every pound of steam flowing through it, the turbine converts 459 BTUs of the steam’s heat energy into mechanical energy to run the electrical generator. Next week we’ll connect a condenser to the steam turbine to see how its efficiency can be improved.

________________________________________ |

Archive for November, 2013

Enthalpy Values in the Absence of a Condenser

Tuesday, November 26th, 2013Enthalpy and the Potential for More Work

Monday, November 18th, 2013|

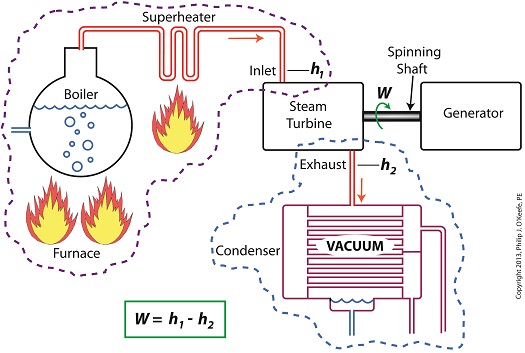

Last time we learned how enthalpy is used to measure heat energy contained in the steam inside a power plant. The higher the steam pressure, the higher the enthalpy, and vice versa, and we touched upon the concept of work, or the potential for a useful outcome of a process. Today we’ll see how to get the maximum work out of a steam turbine by attaching a condenser at the point of its exhaust and making the most of the vacuum that exists within its condenser. Let’s revisit the equation introduced last time, which allows us to determine the amount of useful work output: W = h1 – h2 Applied to a power plant’s water-to-steam cycle, enthalpy h1 is solely dependent on the pressure and temperature of steam entering the turbine from the boiler and superheater, as contained within the purple dashed line in the diagram below. As for enthalpy h2, it’s solely dependent on the pressure and temperature of steam within the condenser portion of the water-to-steam cycle, as shown by the blue dashed circle of the diagram. Next week we’ll see how the condenser, and more specifically the vacuum inside of it, sets the platform for increased energy production, a/k/a work.

________________________________________ |

Enthalpy and Steam Turbines

Thursday, November 14th, 2013|

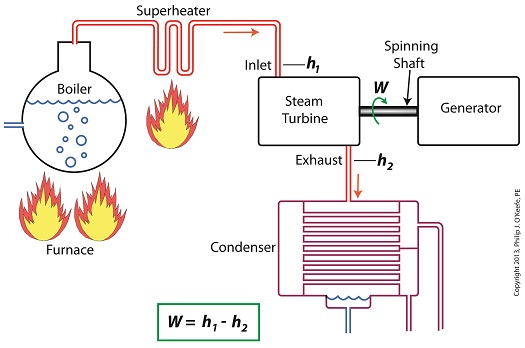

Last time we learned how the formation of condensate within a power plant’s turbine results in a vacuum being created. This vacuum plays a key role in increasing steam turbine efficiency because it affects a property known as enthalpy, a term used to denote total heat energy contained within a substance. For the purposes of our discussion, that would be the heat energy contained within steam which flows through the turbine in a power plant. The term enthalpy was first introduced by scientists within the context of the science of thermodynamics sometime in the early 20th Century. As discussed in a previous blog article, thermodynamics is the science that deals with heat and work present within processes. Enthalpy is a key factor in thermodynamics, and is commonly represented in engineering calculations by the letter h and denoted as, h = u + Pv where u is the internal energy of a substance, let’s say steam; P is the pressure acting upon a specific volume, v, of the steam; and P and v are multiplied together. Pressure is force per unit area and is measured in psi, pounds per square inch. For the purposes of our discussion, it’s the amount of pressure that steam places on pipes containing it. Looking at the equation above, simple math tells us that if we increase the pressure, P, the result will be an increase in enthalpy h. If we decrease P, the result will be a decrease in h. Now, let’s see why this property is important with regard to the operation of a steam turbine. When it comes to steam turbines, thermodynamics tells us that the amount of work they perform is proportional to the difference between the enthalpy of the steam entering the turbine and the enthalpy of the steam at the turbine’s exhaust. What is meant by work is the act of driving the electrical generator, which in turn provides electric power. In other words, the work leads to a useful outcome. This relationship is represented by the following equation, W = h1 – h2 In terms of the illustration below, W stands for work, or potential for useful outcome of the turbine/generator process in the form of electricity, h1 is the enthalpy of the steam entering the inlet of the turbine from the superheater, and h2 is the enthalpy of the steam leaving at the turbine exhaust. We’ll discuss the importance of enthalpy in more detail next week, when we’ll apply the concept to the work output of a steam turbine.

________________________________________ |

Vacuum in a Power Plant Condenser

Tuesday, November 5th, 2013|

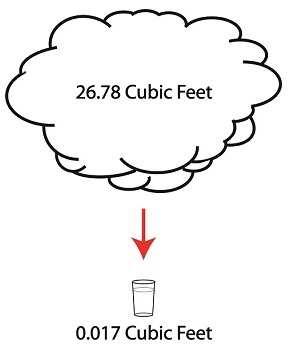

Last time we discussed the key functions of the make-up valve in the power plant water-to-steam cycle. Today we’re going to talk about a vacuum. No, not the kind you use around the house, the kind that’s created by the condenser inside a power plant. As discussed previously, the condenser is a piece of equipment that turns turbine exhaust steam back into water. The water that’s formed during this process is known as condensate, and its density is higher than that of the steam it shares space with inside the condenser. That difference in density is what creates the vacuum inside the condenser vessel. Put another way, the increase in density along with the condenser’s airtight design prevent air from rushing in from outside to occupy any of the space inside the condenser, a desirable condition from an efficiency standpoint. But to understand how all this works we’ll first have to gain an understanding of what is meant by density. A textbook would define it as the mass of a substance divided by the amount of space that that substance occupies. Let’s take steam and water for example. One pound of steam at 212°F forms a vapor cloud that occupies 26.78 cubic feet of space. If we condensed that pound of steam back into water at the same temperature, it would just about fit into a 16 ounce glass and occupy a mere 0.017 cubic feet. The huge difference in their volumes is due to the fact that steam contains more than five times the heat energy that unheated water does. That energy makes the molecules in a cloud of steam more active, causing them to collide against each other with great force, spread apart, and occupy a larger space. If you’re wondering what change in density has to do with vacuum in the condenser, allow me to offer an analogy. Ever canned any produce, like tomatoes, in glass jars to over-winter? Not likely, as this once common survival tactic has nearly become a lost art. But the vacuum created inside the condenser is much like the vacuum created within a mason jar during canning. Inside the glass mason jar, a small space is intentionally left between the tomatoes and lid. During the process of boiling, or heat sterilization, this space fills with steam. Then during cooling the trapped steam condenses into water. This condensation creates the vacuum that sucks down on the jar’s lid, giving it an airtight seal, a condition which won’t allow bacteria to grow on our canned foods. You see, like us bacteria need oxygen to live, but thanks to the vacuum inside our cooked mason jar no air containing oxygen will remain inside to harbor it. Next time we’ll continue our discussion on vacuum to see how it’s used to increase a steam turbine’s efficiency.

________________________________________ |