|

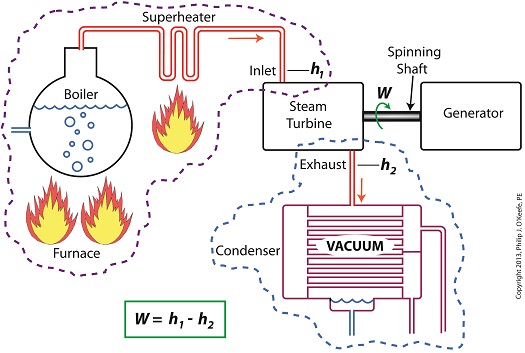

Last time we learned how enthalpy is used to measure heat energy contained in the steam inside a power plant. The higher the steam pressure, the higher the enthalpy, and vice versa, and we touched upon the concept of work, or the potential for a useful outcome of a process. Today we’ll see how to get the maximum work out of a steam turbine by attaching a condenser at the point of its exhaust and making the most of the vacuum that exists within its condenser. Let’s revisit the equation introduced last time, which allows us to determine the amount of useful work output: W = h1 – h2 Applied to a power plant’s water-to-steam cycle, enthalpy h1 is solely dependent on the pressure and temperature of steam entering the turbine from the boiler and superheater, as contained within the purple dashed line in the diagram below. As for enthalpy h2, it’s solely dependent on the pressure and temperature of steam within the condenser portion of the water-to-steam cycle, as shown by the blue dashed circle of the diagram. Next week we’ll see how the condenser, and more specifically the vacuum inside of it, sets the platform for increased energy production, a/k/a work.

________________________________________ |

Posts Tagged ‘superheater’

Enthalpy and the Potential for More Work

Monday, November 18th, 2013Enthalpy and Steam Turbines

Thursday, November 14th, 2013|

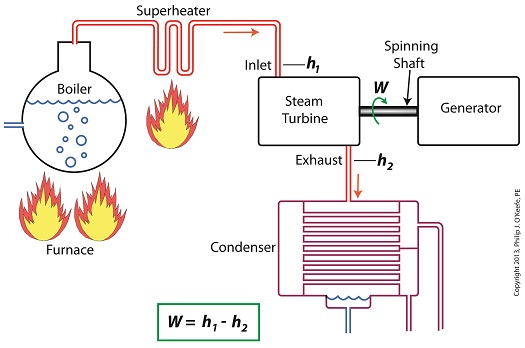

Last time we learned how the formation of condensate within a power plant’s turbine results in a vacuum being created. This vacuum plays a key role in increasing steam turbine efficiency because it affects a property known as enthalpy, a term used to denote total heat energy contained within a substance. For the purposes of our discussion, that would be the heat energy contained within steam which flows through the turbine in a power plant. The term enthalpy was first introduced by scientists within the context of the science of thermodynamics sometime in the early 20th Century. As discussed in a previous blog article, thermodynamics is the science that deals with heat and work present within processes. Enthalpy is a key factor in thermodynamics, and is commonly represented in engineering calculations by the letter h and denoted as, h = u + Pv where u is the internal energy of a substance, let’s say steam; P is the pressure acting upon a specific volume, v, of the steam; and P and v are multiplied together. Pressure is force per unit area and is measured in psi, pounds per square inch. For the purposes of our discussion, it’s the amount of pressure that steam places on pipes containing it. Looking at the equation above, simple math tells us that if we increase the pressure, P, the result will be an increase in enthalpy h. If we decrease P, the result will be a decrease in h. Now, let’s see why this property is important with regard to the operation of a steam turbine. When it comes to steam turbines, thermodynamics tells us that the amount of work they perform is proportional to the difference between the enthalpy of the steam entering the turbine and the enthalpy of the steam at the turbine’s exhaust. What is meant by work is the act of driving the electrical generator, which in turn provides electric power. In other words, the work leads to a useful outcome. This relationship is represented by the following equation, W = h1 – h2 In terms of the illustration below, W stands for work, or potential for useful outcome of the turbine/generator process in the form of electricity, h1 is the enthalpy of the steam entering the inlet of the turbine from the superheater, and h2 is the enthalpy of the steam leaving at the turbine exhaust. We’ll discuss the importance of enthalpy in more detail next week, when we’ll apply the concept to the work output of a steam turbine.

________________________________________ |

Boiler Feed Water, A Special Kind of Condensate

Tuesday, October 22nd, 2013|

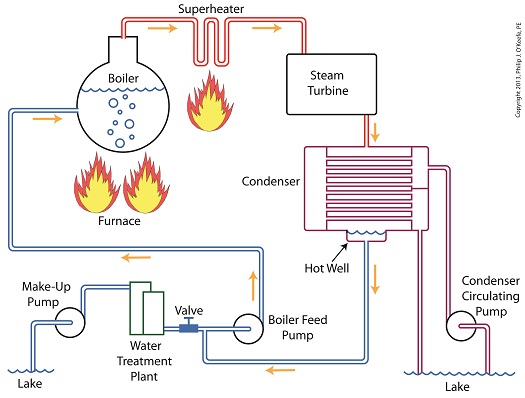

Last time we learned how the condenser within a power plant acts as a conservationist by transforming steam from the turbine exhaust back into water. This previously purified water, or condensate, contains valuable residual heat energy from its earlier journey through the power plant, making it perfect for reuse within the boiler, resulting in both water and fuel savings for the plant. Today we’ll take a look at a highly pressurized form of condensate known as boiler feed water and how it helps the power plant save money by recycling residual heat energy in the steam and water cycle. Let’s begin by integrating the condenser into the big picture, the complete water-to-steam power plant cycle, to see how it fits in. The illustration shows that both the make-up pump and the condenser circulating water pump draw water from the same supply source, in this case a lake. The circulating water pump continuously draws in water to keep the condenser tubes cool, while the make-up pump draws in water only when necessary, such as when initially filling the boiler or to make up for leaks during operation, leaks which typically occur due to worn operating parts. In a nutshell, the condenser recycles steam from the turbine exhaust for its reuse within the power plant. The journey begins when condensate drains from the hot well located at the bottom of the condenser, then gets siphoned into the boiler feed pump. If you recall from a previous article, the boiler feed pump is a powerful pump that delivers water to the boiler at high pressures, typically more than 1,500 pounds per square inch in modern power plants. After its pressure has been raised by the pump, the condensate is known as boiler feed water. The boiler feed water leaves the boiler feed pump and enters the boiler, where it will once again be transformed into steam, and the water-to-steam cycle starts all over again. That is, boiler feed water is turned to steam, it’s superheated to drive the turbine, then condenses back into condensate, and finally it’s returned to the boiler again by the boiler feed pump. Trace its journey along this closed loop by following the yellow arrows in the illustration. While you were following the arrows you may have noticed a new valve in the illustration. It’s on the pipe leading from the water treatment plant to the boiler feed pump. Next time we’ll see how this small but important item comes into play in the operation of our basic power plant steam and water cycle. ________________________________________ |

Superheater Construction and Function

Sunday, September 15th, 2013|

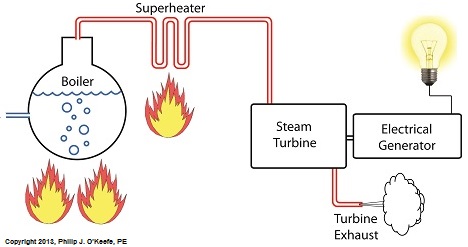

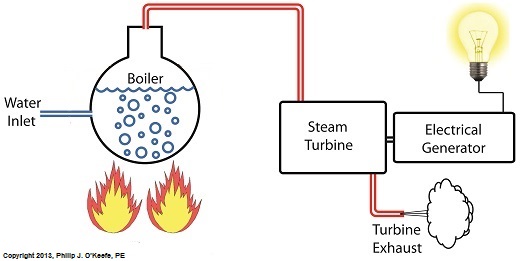

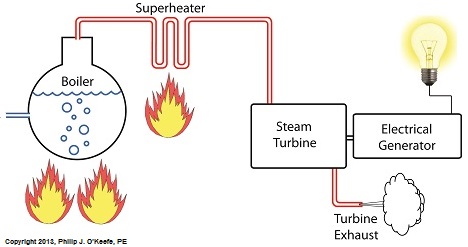

Power plants produce electrical energy for consumers to use, whether at home or for business, that’s obvious enough, but did you know that in order to produce that electrical energy they must first be supplied with heat energy? The heat energy that power plants crave comes from a fuel source, such as coal, oil, or natural gas, by way of a burning process. Once the heat energy is released from the coal through burning, it’s transported into a steam turbine by way of superheated steam, which is supplied to it by a piece of equipment named, appropriately enough, a superheater. So what is a superheater and how does it function? Take a look at the illustration below. The superheater looks like a W. It’s actually a cascading array of bent steam pipe, situated above a source of open flames which are produced by the burning of a fuel source. A photo of an actual superheater is shown below. So how many bends are in a superheater? Enough to fill the needs of the particular power plant it is supplying energy to. Since all power plants are designed differently, we’ll keep things in general terms. The many bends in the superheater’s pipes form a circuitous path for steam to flow as it follows a path from the boiler to the steam turbine. The superheater’s unique construction gives the steam flowing through it maximum exposure to heat. In other words, the bends increase the time it takes for the steam to flow through the superheater. The more bends that are present, the longer the steam will be exposed to the flame’s heat energy, and the longer that exposure, the more heat energy that is absorbed by the steam. Superheating routinely results in temperatures in excess of 1000°F. This superheated steam is laden with abundant heat energy which will keep the steam turbine spinning and the generator operating. The net result is millions of watts of electrical power. As we learned in a previous blog, the superheater is designed to provide the turbine with sensible heat energy to prevent steam from completely desuperheating, which would result in dangerous condensation inside the turbine. The newly added superheater is a major improvement to a power plant’s water-to-steam cycle, but there’s still plenty of waste and inefficiency in the system, which we’ll discuss next week.

________________________________________ |

Condensation Inside the Steam Turbine

Sunday, September 8th, 2013|

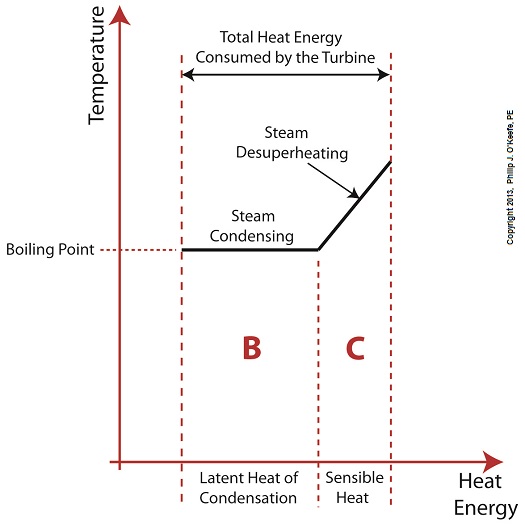

Did you know that water droplets traveling at high velocity can take on the force of bullets? It can happen, particularly within steam turbines at a power plant during the process of condensation, where steam transforms back into water. The last couple of weeks in this blog series we’ve been talking about the steam and water cycle within electric utility power plants, how heat energy is added to water during the boiling process, and how turbines run on the sensible heat energy that lies within the superheated steam vapor supplied by boilers and superheaters. We learned that without a superheater there is a very real possibility that the steam’s temperature can fall to mere boiling point. When steam returns to boiling point temperature an undesirable situation is created. The steam begins to condense into water within the turbine. To understand how this happens, let’s return to our graph from last week. It illustrates the situation when there’s no superheater present in the power plant’s steam cycle. Figure 1

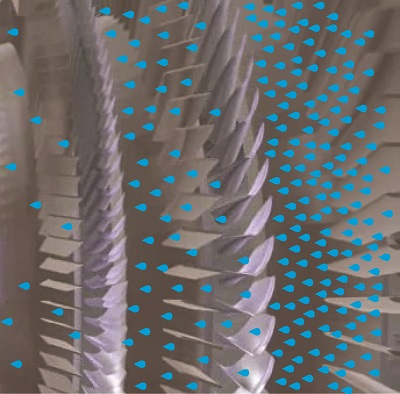

After consuming all the sensible heat energy in phase C in Figure 1, the only heat energy which remains available to the turbine is the latent heat energy in phase B. If you recall from past blog articles, latent heat energy is the energy added to the boiler water to initiate the building of steam. As the turbine consumes this final source of heat energy, the steam begins a process of condensation while it flows through the turbine. You can think of condensing as a process that is opposite to boiling. During condensation, steam changes back into water as latent heat energy is consumed by the turbine. When the condensing process is in progress, the temperature in phase B remains at boiling point, but instead of pure steam flowing through the turbine, the steam will now include water droplets, a dangerous mixture. As steam flows through the progressive chambers of turbine blades, more of its latent heat energy is consumed and increasingly more steam turns back into water as the number of water droplets increases. Figure 2 – Water Droplets Forming in the Turbine

The danger comes in when you consider that the steam/water droplet mixture is flying through the turbine at hundreds of miles per hour. At these high speeds water droplets take on the force of machine gun bullets. That’s because they act more like a solid than a liquid due to their incompressible state. In other words, under great pressure and at high speed water droplets don’t just harmlessly splash around. They hit hard and cause damage to rapidly spinning turbine blades. Without a working turbine, the generator will grind to a halt. So how do we supply the energy hungry turbine with the energy contained within high temperature superheated steam in sufficient quantities to keep things going? We’ll talk more about the superheater, its function and construction, next week.

________________________________________ |

Desuperheating in the Steam Turbine

Monday, September 2nd, 2013|

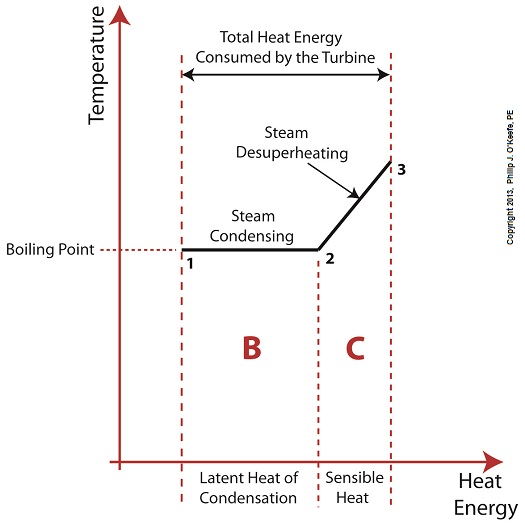

Last time we learned that the addition of a superheater to the electric utility power plant steam cycle provides a ready supply of high temperature steam, laden with heat energy, to the turbine, which in turn powers the generator. But this isn’t its only job. One of the superheater’s most important functions is to regulate the ongoing process of desuperheating that takes place as the turbine consumes heat energy. To understand this, let’s see what takes place if the superheater were to be removed from its position between the boiler and turbine. Figure 1

Without the superheater, the only available remaining source of sensible heat energy to the turbine would come from the meager amount present in phase C steam as shown in Figure 1. If you’ll recall from a past blog, the sensible heat energy contained in superheated steam is the best source of energy for a steam turbine, because it’s able to keep it operating most efficiently. As the turbine consumes the heat energy in phase C, starting at point 3 and continuing to point 2, the steam it’s consuming is in the process of desuperheating, as evidenced by the downward slope between the two points. Desuperheating is an engineering term which means that as sensible heat energy is removed from the steam due to its use by the turbine, there will be a resulting drop in steam temperature. And if this process were to continue without the compensatory function provided by the addition of a superheater to the steam cycle, the steam’s temperature would eventually return to mere boiling point, at point 2. This is an undesirable thing. With the steam’s temperature at boiling point, the only remaining source of heat energy to the turbine is the latent heat energy of phase B. This heat energy will lead to an undesirable circumstance for the operation of our power hungry turbine as we will see next week. ________________________________________ |

Superheating, Part 2

Sunday, August 25th, 2013|

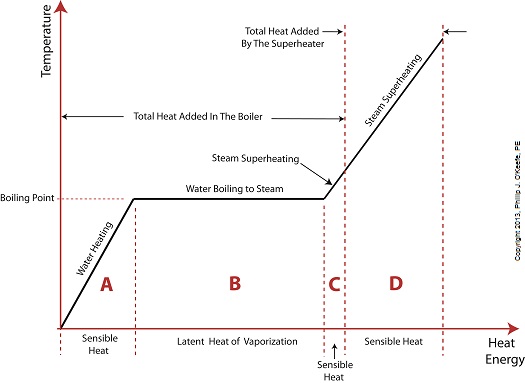

Last time we added a piece of equipment called a superheater, positioned between the boiler and steam turbine, to our basic electric utility power plant steam and water cycle. Its addition enables a greater and more consistent supply of heat energy to the steam which powers the turbine. How much more? Let’s look at Figure 1 to get an idea. Figure 1

You may have noticed that our illustration lacks numerical representation. That’s because power plants are designed differently, depending on fuels used and power output required. So unless we’re talking about a particular power plant, number values would be impractical. For example, I could specify a boiling point of 596°F at 1,500 pounds per square inch (PSI), and a superheater outlet temperature of 1,050°F at 1,200PSI, and I could make note of esoteric things like enthalpy (British Thermal Units per pound mass) values on the Heat Energy axis. But to facilitate our discussion we’ll keep things simple and focus on the general process. Figure 1 shows in phase D the additional heat energy being added to the steam, thanks to the superheater. This is significantly more than had been added by the boiler alone, as represented by phase C. The turbine consumes heat energy added in phases C and D and converts it into mechanical energy to drive the generator, resulting in electrical energy being provided to consumers in the most energy efficient way possible. But increasing power output and efficiency isn’t the superheater’s only job. The heat it adds during phase D ensures the turbine’s safe operation when it’s cranking at full capacity, as represented by the superheated steam zones of phases C and D. Next week we’ll discover how the superheater prevents a destructive process known as condensing from occurring inside the turbine. ________________________________________ |

Superheating, Part I

Monday, August 19th, 2013|

Last time we learned that our power plant boiler as presently designed doesn’t do a good job of producing ample amounts of superheated steam, the kind of steam that turbines need to spin and power generators. During the process of superheating the more heat energy that’s added to the steam in our boiler, the higher its temperature becomes. However, our boiler can only produce a limited amount of superheated steam as it stands now. So how do we get more heat energy into the superheated steam? Take a look at the illustration below for the solution to the problem. You’ll note a prominent new addition to our illustration. It’s called a superheater. The superheater performs the function of raising the temperature of the steam produced in our boiler to the incredibly high temperatures required to run steam turbines and electrical generators down the line, as explained in my blog on steam turbines. The superheater adds more heat energy to the steam than the boiler can alone. In fact, the amount of heat energy in the superheated steam produced with our new design is proportional to the amount of electrical energy that power plant generators produce. Its addition to our setup will result in more energy supplied to the turbine, which in turn spins the generator. The result is more electricity for consumers to use and a more efficiently operating power plant. But inefficiency isn’t the only problem addressed by the superheater. We’ll see what else it can do next week. ________________________________________ |