| Have you ever had the divine experience of remodeling a major-use room of your house? Was the general contractor you employed able to understand what you wanted, plan out the work according to your requirements, and finish the job to your satisfaction? Maybe you had the unfortunate experience of hiring one that forgot your requirements, made things up as they went along, and stuck you with a room that looked awful, violated building codes, and didn’t meet your needs.

Now imagine what would happen if a medical device company took this haphazard approach to designing new products. Suppose the company’s engineers ignored the input of regulatory, marketing, procurement, quality control, and manufacturing staff? What if they chose not to follow applicable industry standards for performance and safety? And what if they failed to check design calculations or test prototypes for errors before putting the device into production and introducing it to the marketplace? The result is likely to be unfavorable, just like your contractor forgetting that you wanted a black granite countertop, not a beige one. To help eliminate painful and costly scenarios such as these, the FDA requires that medical device manufacturers establish and maintain procedures to control the design of Class II and III devices, and even some Class I. This requirement for a system of design controls is part of the Quality System Regulation (QSR) under Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations. In case you’re not too familiar with the Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21 gives the FDA legal authority to regulate food, drugs, and medical devices in the United States. So what falls under the premises of FDA design controls? Well, the FDA requires that a medical device company develop procedures for:

For now, let’s focus on Design and Development Planning and Design Input Procedures. In the Design and Development Planning Procedure companies must carefully plan who will be involved in each phase of product development, as well as how they will interact, all in an effort to ensure that information flows and design requirements are met. The right pool of people would include design engineers, in addition to those employees responsible for making sure that regulations are complied with and those who are charged with securing intellectual property rights to the design. Then there are those who must acquire the physical materials required to manufacture the device and those who will do the actual manufacturing of it. Also, those responsible for quality control, marketing, sales, and product service should be involved. Perhaps others should be involved as well. Mind you, the Design and Development Planning Procedures are not set in stone. They must be regularly reviewed and updated as the project evolves. Now let’s talk about Design Input, which is another term for a design requirement. These inputs can come from inside or outside the company. An example of a requirement coming from within is when Marketing stipulates that the maximum manufacturing cost of the device should not exceed $150 in order to maintain an acceptable margin of profit and be most competitive in the marketplace. A design requirement coming from outside the company would include industry standards that make specific requirements, such as requiring that the device in question be designed to protect its electronics from radio frequency interference. Next time we’ll continue our discussion on medical device design by exploring Design Output, Design Verification, and Design Review Procedures. _____________________________________________ |

Archive for August, 2010

Medical Device Design Controls – Planning and Input

Sunday, August 29th, 2010FDA Classifications for Medical Devices – Special Controls

Monday, August 23rd, 2010|

For the last couple of weeks we’ve been discussing FDA medical device risk classifications, namely Classes I, II, and III. We also began discussing the FDA system of regulatory controls governing each class, starting with General Controls. This week we’ll examine the more stringent guidelines that come into play within Special Controls. As you would imagine from the name, Special Controls come into play when General Controls aren’t deemed to be sufficient to deal with the situation. Class II and III medical devices, because they pose a higher level of risk to patients than Class I, generally require more FDA supervision than mere General Controls. These devices tend to fall under the auspices of Special Controls. Special Controls include things like special labeling requirements, complying with mandatory performance standards, and perhaps requiring that a manufacturer conduct a Post Market Surveillance (PMS) study. In case you’re wondering, a PMS may be required by the FDA to collect data after a medical device is sold, should there be any unexpected adverse events involving the device. A study of this data would aid in an investigation to determine the number of events, the cause of the events, and how to correct any problems that led to the events. Let’s look at some examples of how Special Controls apply to Class II medical devices. One example would be a cranial molding helmet. These helmets are often used with infants to reshape their skulls into becoming more symmetric. Due to the nature of this device’s application on such a delicate patient, Special Controls include a requirement for special labeling. In this case, the labeling must include warnings to physicians and parents that precautions must be taken during its application to protect patients from possible injury, including eye trauma and impairments of brain growth. Another example would be sutures. Yes, they are considered to be Class II medical devices. In this case, Special Controls require that sutures meet “mandatory performance standards.” What are “mandatory performance standards?” Well, they generally include industry consensus standards for particular medical devices. They are based on industry-wide accepted guidelines to ensure proper product performance. In this example, industry standards for suture material contain specific guidelines as to material composition, diameter size, mechanical strength, and biocompatibility. Adherence to these standards provides the highest assurance that sewn incisions won’t break open when the suture is stressed or the suture material won’t cause some sort of adverse reaction with the patient’s skin. As specific as Special Controls can be, they are sometimes not enough. On these occasions the FDA states, “Class III devices are those for which insufficient information exists to assure safety and effectiveness solely through General or Special Controls.” Under these circumstances more regulatory control may be imposed. This is the case when dealing with medical devices directly responsible for supporting/sustaining human life, such as a cardiac defibrillator. One such FDA control method that goes beyond Special Controls is the requirement to submit a Pre Market Approval application (PMA) to the FDA for approval. This PMA is subject to the most stringent FDA requirements. As a part of the PMA process a company must demonstrate the safety and effectiveness of a new medical device design by producing data and documentation obtained during “adequate and well-controlled” clinical trials. In our series on FDA Classifications for Medical Devices we have merely grazed the surface. Depending on the device in question there may be a myriad of other considerations, so please consult the FDA’s web site for the complete picture: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/default.htm. _____________________________________________ |

FDA Classifications for Medical Devices – General Controls

Sunday, August 15th, 2010|

When I was a kid in Chicago back in the 1960s there was a show on television called Bozo’s Circus. Lucky kids were picked from the audience to play a bucket game. There were six buckets in a row, as I remember, each about a foot from the last. The kids had to stand in front of the first bucket to play. By the time the kids got to throw their ball into Bucket No. 6 there was probably ten feet for the ball to travel. So what would happen if the ball didn’t sink into the desired bucket, which would happen more often than not it seemed? Then Ringmaster Ned would direct Cookie the Clown to chase down the rogue balls. So what does this have to do with the FDA and medical devices? Well, in the loosest of terms you may think of the FDA’s classification system as Buckets 1 through 6 and Ringmaster Ned as the regulatory agent of the game. Okay, I’m really stretching on this analogy, but I did want to introduce some levity into the discussion! Last week we discussed the fact that the FDA classifies medical devices into three main categories, Classes I, II and III, Class I devices posing the least risk to patients, Class III the most. Now we’ll see how the FDA regulatory control system functions to oversee the medical devices within each classification. To begin with, you should be aware that regulatory controls are themselves divided into General and Special Control categories. In this article we’ll focus on General Controls. General Controls can apply to medical devices within all three FDA risk classifications. They include requirements for: — Registering of medical device manufacturers, distributors, repackagers, and relabelers with the FDA. This registration basically lets the FDA know they exist as an entity, and it gives the Agency information about who to contact should the need arise. — Listing medical devices with the FDA so the Agency can keep track of what kind of devices are being marketed in the United States. — Manufacturing devices in accordance with FDA Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). GMP regulations require a quality approach to manufacturing, an approach which is designed to minimize or eliminate instances of contamination, defect, and error which could contribute to harm or kill a patient. GMP regulations address issues like sanitation, quality control, complaint handling, and record keeping. Effective complaint handling and record keeping systems are key in identifying and resolving issues that may pose increased risk to patients. — Labeling devices. The FDA requires that medical device labeling provide explicit directions for use. The labels must also contain appropriate warnings as needed to ensure the safe and effective use of the device. — Submitting a Premarket Notification to the FDA for approval before marketing a device, also referred to as a 510(k) within the industry. This name comes from the section of the federal regulation that deals with it, that is to say, companies must submit 510(k) documents to the FDA to demonstrate that the device they wish to market is comparably safe and effective as other equivalent devices already on the market. A 510(k) can only be submitted if Premarket Approval (PMA) for the device is not required. We’ll talk more about this in a future article on Special Controls. Now, because they pose such a low level of risk, many Class I medical devices are exempt from the requirement for 510(k) submissions altogether, and they may even be exempt from compliance with GMP regulations. In a nutshell, General Controls help the FDA keep track of what products are being sold by whom, and how effective and safe those products are. It also provides guidelines to medical device companies to help ensure their introduction of safe and effective products to the public. So what happens when a device falls outside of the parameters of the General Controls watch? That’s when more stringent guidelines come into play, for it has now entered the realm of Special Controls. _____________________________________________ |

FDA Classifications for Medical Devices

Sunday, August 8th, 2010|

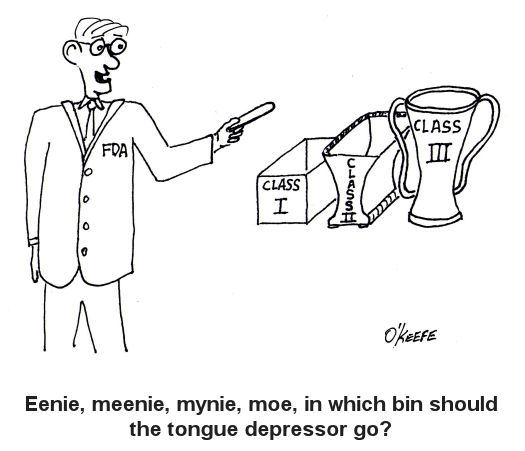

Hardly a week goes by that the FDA, that is the Food and Drug Administration, is not in the news. From the recall of drugs found to be harmful after the fact, to investigations of medical device suppliers and inspections of salmonella contamination at meat processing plants, the FDA is responsible for overseeing and regulating a wide range of products and processes. It’s stated purpose being: The FDA is responsible for protecting the public health by assuring the safety, efficacy, and security of human and veterinary drugs, biological products, medical devices, our nation’s food supply, cosmetics, and products that emit radiation. http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/WhatWeDo/default.htm From its humble beginnings at the beginning of the last century as the Pure Food and Drug Act, it has grown to regulate more than $1 trillion worth of consumer goods, about 25% of that said to be attributable to consumer goods expenditures in the United States. In 1976, the FDA began classifying medical devices, using a three-tiered system to distinguish them according to level of risk to patients. Class I devices present the lowest level of risk and requires the least regulatory control, while Classes II and III represent higher levels of risk. Just to give you some perspective, Class I medical devices include things like tongue depressors, bedpans, arm slings, and hand-held surgical instruments. In the Class II category are things like surgical drapes, blood pressure cuffs, catheters, wheelchairs, heating pads, and x-ray film processing machines. And I’m sure you’ve guessed by now that Class III devices are for the heavy-hitters, including things like defibrillators, heart valves, and implanted cerebral stimulators. So why does the FDA classify medical devices? Practicality is one key reason. It would be highly impractical, if not downright impossible, for the FDA to subject manufacturers of low risk Class I devices, like tongue depressors, to the same scrutiny as manufacturers of Class III devices, such as heart valves, etc. Along with miles of red tape would come a huge financial burden that would effectively raise the price of your common tongue depressor through the roof and, undoubtedly, force the manufacturer out of business. Hand in hand with medical device classifications are regulatory controls imposed by the FDA. We’ll see how they fit into the picture next time. _____________________________________________ |

Where Are The Best Engineers?

Sunday, August 1st, 2010|

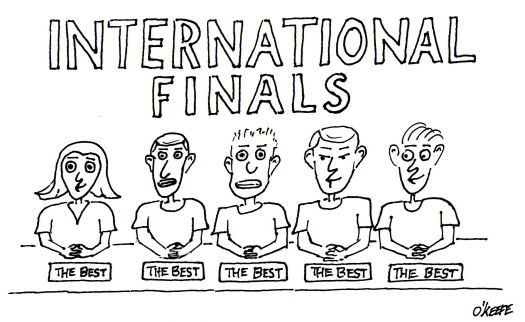

Smart people say smart things, right? Consider the following quote by Duke University adjunct professor Vivek Wadhwa, who testified before a House Committee: “If a certain type of engineering job can be done more cost effectively in India or China, why should we invest in graduating more of those types of engineers?” Professor Wadhwa is said to have spoken before the House as a means of response to many engineering students’ fears of not finding a job upon graduation due to outsourcing, according to a somewhat dated, yet still applicable, article by Ed Burnette at zdnet.com. ( http://www.zdnet.com/blog/burnette/us-vs-china-vs-india-in-engineering/125 ) As to the quality of engineers graduating from China and India, Professor Wadhwa states, “…the vast majority of Indian and Chinese graduates are not close to the standards of US graduates.” And this sentiment is apparently shared by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry and the World Bank, who claim that 64 percent of Indian employers surveyed are: “’somewhat,’ ‘not very,’, or ‘not at all’ satisfied with the quality of engineering graduates’ skills…”, this according to taatparya’s blog at vidyaweb.com. ( http://vidyaweb.com/?q=node/17 ) Despite the poor review, one Indian writer, Swati, in saching.com poses this observation, “Then why are Indian software engineers in demand all over the world,” and continues to explain why: Because “Indians are very hard working and they go through competition in every stage of life. If you live in a Western country, you will never be able to co-relate what hard work means in Indian culture. India has 1.1 billion people and a large middle class, therefore competition and hard work starts right from the early school level itself. There is no concrete social programs and people know that they have no choice except to work hard, additionally there are social pressures to excel in life.” Values, apparently, that Americans appear to lack. ( http://www.saching.com/Article/Quality-of-Engineering-in-India—Software-Engineer-vs–Professor/376 ) Let’s return to our home shores for a moment. No doubt you have read an article or two concerning the recently publicized outcome of this year’s round of state academic testing on our American children. As in years past, they have not fared well. In my hometown, which is said to be representative of the norm, only 46% of 3rd graders can read. The results for math and science testing are, expectedly, even worse. So who or what is to blame for this poor showing? We know who the usual finger pointing is directed at. And how is the problem to be solved? Most of us are familiar with the proposed solutions as well. If you take the time to read the cited articles in their entirety, a picture emerges. It’s a picture showing diverse people airing similar complaints. Times are changing, of that we can all be certain. We’ll take a closer look at some of the world’s engineering challenges in the weeks to follow. _____________________________________________ |