|

During 6th grade science we had a chapter on Simple Machines, and my textbook listed a common lever as an example, the sort that can be used to make work easier. Its illustration showed a stick perched atop a triangular shaped stone, appearing very much like a teeter-totter in the playground. A man was pushing down on one end of the stick to move a large boulder with the other end. Staring at it I thought to myself, “That doesn’t look like a machine to me. Where are its gears?” That day I learned about more than just levers, I learned to expect the unexpected when it comes to machines. Last time we learned that under patent law the machine referred to in federal statute 35 USC § 101 includes any physical device consisting of two or more parts which dynamically interact with each other. We looked at how a purely mechanical machine, such as a diesel engine, has moving parts that are mechanically linked to dynamically interact when the engine runs. Now, lets move on to less obvious examples of what constitutes a machine. Would you expect a modern electronic memory stick to be a machine? Probably not. But, under patent law it is. It’s an electronic device, and as such it’s made up of multiple parts, including integrated circuit chips, resistors, diodes, and capacitors, all of which are soldered to a printed circuit board where they interact with one another. They do so electrically, through changing current flow, rather than through physical movement of parts as in our diesel engine. A transformer is an example of another type of machine. An electrical machine. Its fixed parts, including wire coils and steel cores, interact dynamically both electrically and magnetically in order to change voltage and current flow. Electromechanical, the most complex of all machine types, includes the kitchen appliances in your home. They consist of both fixed and moving parts, along with all the dynamic interactions of mechanical, electronic, and electrical machines. Next time we’ll continue our discussion on the second hurtle presented by 35 USC § 101, where we’ll discuss what is meant by article of manufacture. ___________________________________________ |

Archive for April, 2013

Determining Patent Eligibility – Part 4, Machines of a Different Kind

Sunday, April 28th, 2013Determining Patent Eligibility – Part 3, What Constitutes a Machine?

Sunday, April 21st, 2013Determining Patent Eligibility – Part 2, Utility

Sunday, April 14th, 2013|

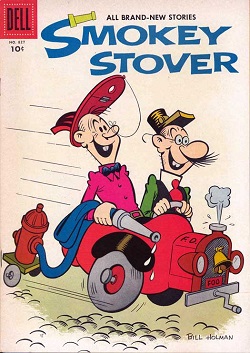

When I was growing up in the 1960s the Chicago Tribune featured a comic strip by Bill Holman called Smokey Stover. Smokey was a fireman who had all sorts of ridiculous, nutty, and even bazaar inventions, like his two-wheeled fire truck called the “Foomobile.” In the real world his inventions could never work, but that didn’t stop me from being a kid and enjoying Smokey’s goofy adventures. Smokey’s fire truck would never pass a patent test. Why? Because it wouldn’t get past the first requirement for patentability, that is, utility. Last time we introduced the federal laws governing patents as found in Title 35, Section 101, of the United States Code (USC), 35 USC § 101 for short. It sets out requirements for patentability, and the first hurdle that an invention must jump is that it must possess the quality of utility. In other words, it must be useful. This quality of utility prevents ridiculous and/or hypothetical devices, such as Smokey’s Foomobile, from receiving a patent. Because the Foomobile consists of an engine and two wheels mounted on a single axle, there’s nothing to keep it from falling over. The weight of its engine makes it front-heavy and unstable. The nutty vehicle will tip forward, and its front bumper will become wedged in the ground. The Foomobile is just not capable of passing the test of utility because it cannot be operated as intended – Smokey would never make it to the scene of the fire – and it’s unable to provide any identifiable benefit to its users. Once the hurdle of proving an invention’s utility is passed, the next considerations for patent eligibility must be addressed. Is the invention a machine? A process? Just what defines a machine? Is it something with gears and a motor? Next time we’ll see how within the context of patent eligibility, the word machine can apply to things which are not at all mechanical. ___________________________________________ |

Determining Patent Eligibility – Part 1

Sunday, April 7th, 2013|

Last time I introduced the concept of intellectual property, or IP. We learned that IP in the eyes of the law is recognized as a creation of an individual inventor’s mind, worthy of commercial value. It goes to follow that those inventions that have been awarded patents are also a form of IP, because they represent the working ideation of the inventor’s mind. As such, the patent grants the inventor the sole legal right to profit from the invention to the exclusion of all others. So all you need is an idea, and you can apply for a patent, right? Well, not really. There are in fact a number of tests that potentially patentable inventions must pass. Federal laws governing patents have been in existence since 1790. They were put in place to give inventors the means to legally protect their exclusive rights to profit from their inventions in our new country. The first patent was awarded to inventor Samuel Hopkins on July 31st of that year, for a process he created to make potash, an ingredient used to make fertilizer. Since that time, the patent laws have been continually revised and expanded to improve the patenting process, something that became necessary due to the explosion of patentable technological innovations after the Industrial Revolution started in the 19th Century. In July of 1952, the basic structure of modern patent law was laid out by Title 35 of the United States Code (USC). Title 35 is a set of laws drafted by Congress that contains all federal statutes governing patents. Within Title 35 is found Section 101. It’s the part that addresses patent eligibility. This Section is commonly referred to within the trade by patent agents and attorneys as 35 USC § 101, shorthand for “Title 35 of the USC, Section 101.” According to 35 USC § 101, in order to be patentable an invention must first be useful. In addition, it must be either a machine, an article of manufacture, a composition of matter, or a process, or it must improve upon an existing machine, article of manufacture, composition, or process. But what does this all really mean? We’ll find out next time. ___________________________________________ |