|

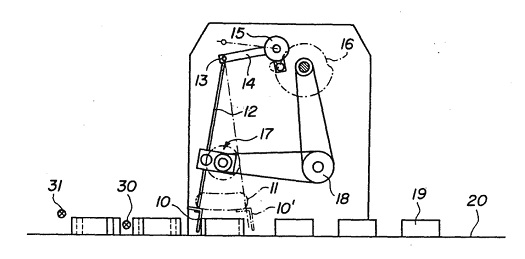

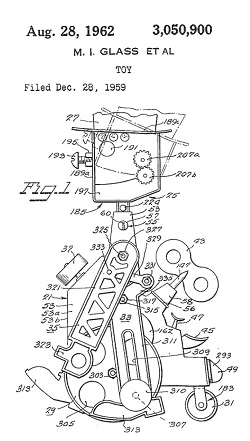

Movies, that is 3D animations, are moving into the courtroom, and intended messages are made clearer than ever as a result. If a picture is worth a thousand words, how much more effective is a moving 3D image? We’ve been viewing a static two-dimensional representation of a machine for the past two blogs. Have you been able to figure it out yet? Here it is again:

Would it help you to understand if I identified it as a piece of food manufacturing equipment equipped with a rake that aligns cookies on a conveyor belt? Would that verbal description allow you to “see” in your mind’s eye how it operates? Unless you had the right technical background, it’s unlikely. Last week we introduced the verbiage person of ordinary skill in the art as a term widely used within patent litigation. This person is said to have the ability to interpret and understand patent drawings, and they typically possess a technical and/or scientific background. But what if participants in a legal proceeding lack this background? Technical experts are often hired on as consultants to attorneys, and in some instances, judges, when clarification is required. These experts provide technical expertise and tutorials on the technology involved in complex cases, and it happens with regularity when the operation of a patented device is in question. By employing 3D animations the expert can show how the device operates, rather than attempt to explain it using the technical language of their profession. The expert works closely with an animation artist to create the animation, providing the technical information that the animator will use to create the fully functional model. Animators do not typically have the technical background to accomplish this on their own and will require an ongoing dialog with the technical expert to create the animation. And now the moment we’ve all been waiting for. Here is our static image brought to life through animation:

The animation commands the viewer’s attention and holds their interest, even if they have no background in engineering or science, and the device’s function is now made clear. It must be noted that in the patent drawing, part of the mechanism lies in front of a steel divider plate and part behind, but for purposes of clarity the entire mechanism has been shown to the front of the plate. Now there’s no doubt as to how the parts move together to even up the rows of cookies on the conveyor belt. Next week we’ll talk about juries, perception, and the advantages of using courtroom animations when at trial. |

Posts Tagged ‘patent infringement’

Courtroom Animations – Bringing Patents to Life

Monday, June 17th, 2013Patent Drawings – “Ordinary Skill in the Art”

Sunday, June 9th, 2013|

Last week I introduced this illustration as a typical patent drawing and asked if you could decipher the riddle of its functionality.

Patent drawings are static, two dimensional (2D) representations of proposed inventions which are meant to be manufactured in three dimensions (3D). As such they present a lot of complex information on a flat page. If you don’t have a clue as to what this machine is, I guarantee you’re not alone. The average person wouldn’t. There’s a bunch of lines, shapes and numbers, but what do they signify? How are they meant to all come together and operate? As a matter of fact, the average person isn’t meant to understand patent drawings. That’s because they’re not what patent courts have defined as a person of ordinary skill in the art, a peculiar term which basically means that the Average Joe or Josephine isn’t meant to be able to interpret them. Rather, the interpretation of patent drawings is left to individuals with specialized skills and training, a particular educational background and/or work experience. These individuals are typically able to view a static 2D image and visualize how the illustrated device moves, how it operates. Those said to fall within the court’s definition as having ordinary skill in the art are in fact often engineers and scientists. Since the average person does not have a background in engineering and science, it can be challenging for patent attorneys to present their cases in the courtroom, particularly when relying on 2D representations alone. That’s where animations come in. Next time we’ll use the magic of animation to transform our cryptic 2D patent illustration into a functional 3D animation of a machine whose operation is easily understood by the average person. ___________________________________________ |

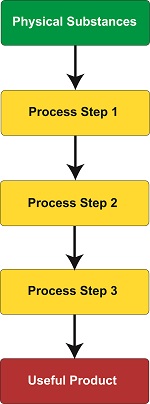

Determining Patent Eligibility – Part 7, Process

Sunday, May 26th, 2013|

We’ve been discussing hurtles which must be jumped in order for an inventor’s creation to be considered for a patent. Federal statutes, namely 35 USC § 101, define the bases of patentability, including providing definitions on key terms, such as what constitutes a machine, an article of manufacture, and a composition of matter. Today we’ll wrap up our discussion on determining patent eligibility when we explore the final hurtle by defining process. To get an understanding of what is meant by process, we must look to the lawsuit of Gottschalk v. Benson, a case involving patentability of a mathematical algorithm within a computer program. In this case the US Supreme Court held that a process is a series of steps or operations that transform substances or came about by way of a newly invented machine. Based on the Court’s definition, a process can be many things, from a production line that transforms corn into corn chips within a food manufacturing plant to a mathematical algorithm running within software on the platform of a newly devised type of computer. However, the term usually pertains to a series of operations or steps, most frequently manufacturing in nature, where physical substances are transformed into useful products, that is, they possess the quality of utility, as discussed earlier in this blog series. A “physical substance” is anything of a physical nature existing on our planet.

Before I end this series I’d like to mention that under 35 USC § 101 an invention can be eligible for a patent if it makes a useful and beneficial improvement to an existing machine, article of manufacture, composition of matter, or process. That is to say, something may have already been patented which performs a specific function, but if that is improved upon in any significant way, it may receive a new patent. For example, suppose an improved process for manufacturing food products was developed by adding additional steps to an existing patented process. If this improvement results in benefits such as lowered production costs, increased production rate, or reduced health risks to consumers, then this improved process may be eligible for a patent under 35 USC § 101. Next time we’ll begin an exploration of the growing presence of 3D animations within the courtroom, specifically how they bring static 2D patent drawings to life. ___________________________________________ |

Determining Patent Eligibility – Part 5, Manufactured Articles

Monday, May 6th, 2013|

Imagine having freshly baked pastries available to you all day long, every day, while at work. I’m not talking about someone bringing in a box of donuts to share, I’m talking about baked goods on a massive scale. This is what I experienced in one of my design engineering positions within the food industry. These baked goods constituted the articles of manufacture of the food plant, and they presented a constant temptation to me. Just what constitutes an article of manufacture is another aspect of the second hurtle which must be passed to determine patent eligibility. It is addressed under federal statutes governing the same, 35 USC § 101, and is contained within the same area as the discussion of what constitutes a machine, a subject we took up previously in this series. Why bother defining articles of manufacture? Well, while hearing the patent case of Diamond v. Chakrabarty regarding genetically engineered bacterium capable of eating crude oil, the US Supreme Court saw fit to define the term so as to resolve a conflict between the inventor and the patent office as to whether a living organism could be patented. The net result was the Court declared that in order to be deemed a patentable article of manufacture the object must be produced from either raw or man-made materials by either hand labor or machinery and must take on “new forms, qualities, properties, or combinations” that would not naturally occur without human intervention. In other words, a creation process must take place and something which did not previously exist must be caused to exist. The court’s definition of articles of manufacture encompasses an incredible array of products, much too vast to enumerate here. Suffice it to say that the defining characteristic is that if it should consist of two or more parts, there is no interaction between the parts, otherwise it could be categorized as a machine. In other words, the relationship between their parts is static, unmoving. An example would be a hammer. It’s made up of two parts, a steel head and wooden handle. These parts are firmly attached to one another, so they act as one. Next time we’ll continue our discussion on the second hurtle presented by 35 USC § 101, where we’ll discuss what is meant by composition of matter. |

Determining Patent Eligibility – Part 3, What Constitutes a Machine?

Sunday, April 21st, 2013Utility Patent Basics

Wednesday, October 21st, 2009|

During my engineering career, I’ve encountered quite a few business owners and inventors who are completely in the dark when it comes to intellectual property rights. In particular, there are plenty of misconceptions floating around about utility patents. To learn more about utility patents, I invite you to read an excellent article by attorney Thomas F. Zuber: Patent Law Basics For The Non-practitioner – Part II Of IV: UTILITY PATENTS *This article is for non-practitioners seeking to familiarize themselves with the basics of patent types and patentability requirements. This article is Part II of a four part series. Parts III and IV will follow in biweekly installments, and will address Design Patents and Plant Patents, respectively. Utility patents are the most common type of patent, and they’re what laypersons are usually referring to when using the word “patent.” For an invention to be patented, ….. Read the full article by going to: ________________________________________________________________ |