Posts Tagged ‘food manufacturing plant’

Friday, August 24th, 2018

|

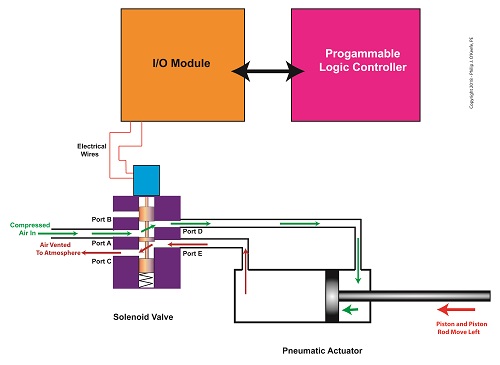

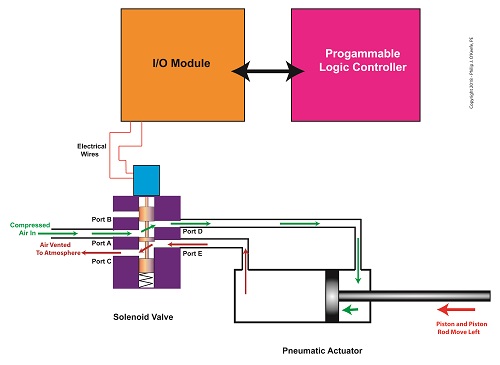

Last time we saw how a solenoid valve operates a pneumatic actuator in a jelly depositor in a food manufacturing plant. The operation was manual. In other words, an electrical switch had to be thrown by hand each time to get the solenoid to work. This can be rather tedious, when you consider the thousands of pastries that must be filled on each production run. Now, let’s see how the solenoid can be automatically turned on and off by an industrial control system.

In food manufacturing plants, industrial control systems are typically made up of programmable logic controllers, otherwise known as “PLCs.” The PLC is an industrial computer that is used to control equipment like conveyor belts, motors, pumps, robots, and solenoid valves. The PLC is connected to Input/Output Modules, or “I/O Modules.”

The I/O modules act as an interface between the computer and the equipment in the plant. As such, they contain a means to connect electrically to the computer and the plant equipment. In the case of our solenoid valve, the PLC computer program would turn the valve’s solenoid on and off. Whether it is turned on or off depends on the computer program’s timing and/or external sensors and how it feeds in conveyor belt/pastry position data to the PLC. The result is the automatic depositing of jelly filling as each pastry passes by the depositor nozzle.

The Depositor’s Industrial Control System

That wraps things up for our blog series on depositors. Next time we’ll move on to a new topic.

Copyright 2018 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: conveyor belt, depositor, food manufacturing plant, i/O Module, Inut/Output Module, PLC, pneumatic actuator, programmable logic controller, solenoid, solenoid valve

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury | Comments Off on The Depositor’s Industrial Control System

Thursday, June 7th, 2018

|

Our last blog introduced a project I oversaw while acting as a design engineer in a food manufacturing plant. The objective was to deposit fruit jelly into raw pastry dough as it whizzed along a production line conveyor belt before being sent off for baking. A special piece of equipment known as a depositor would be required to meet this challenge, and we’ll take a look at how one functions today. In fact, a jelly depositor acts very much as a human heart, as they’re both examples of positive displacement pumps.

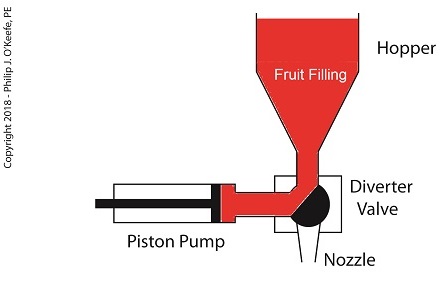

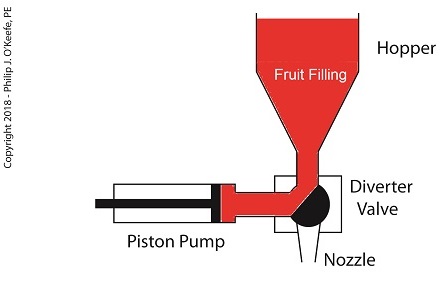

A depositor is a device specifically made for the food industry. It consists of a hopper to hold the product to be deposited, in this case fruit jelly, which is discharged by the hopper into a rotating diverter valve and then on to a positive displacement piston pump. See below.

A Jelly Depositor is a Positive Displacement Pump

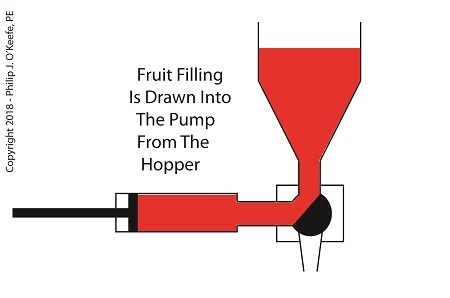

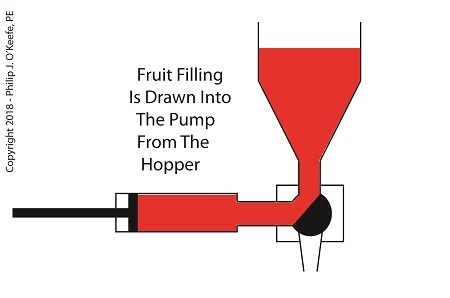

When the diverter valve rotates, a passageway opens to allow jelly to flow from the hopper into the piston pump. A pneumatic actuator, a device we’ll discuss in more depth next time, moves the pump’s piston to the left, away from the diverter valve, which allows the filling to be released into the pump from the hopper. At the end of the piston’s travel a set quantity of fruit jelly filling is drawn into the pump’s housing, just enough to fill one pastry. See below.

The Depositor Draws Filling Into The Pump

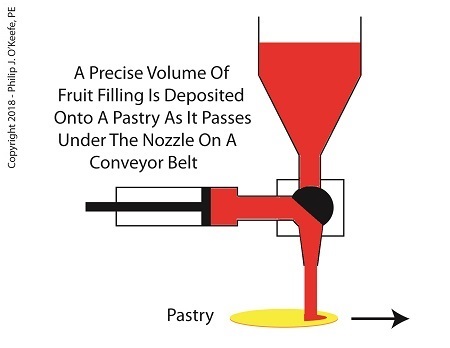

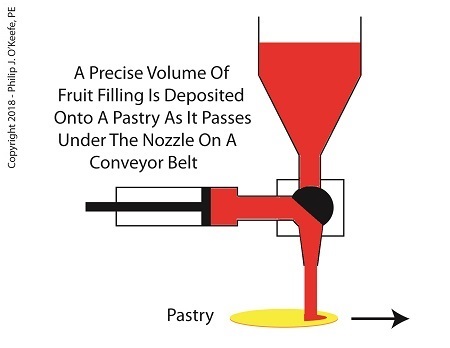

When the diverter valve rotates in the opposite direction, a passageway opens inside the valve that allows jelly filling to move from the pump to the nozzle. As the piston moves back toward the diverter valve the filling is forced out of the pump, through the nozzle, and into the pastry dough. The pump’s piston moves back and forth, that is, away from and then towards the transfer valve, ushering a set quantity of jelly filling through the mechanism each time. See below.

The Depositor Deposits The Filling

Now that we know how the depositor works, next time we’ll discuss the pneumatic actuator’s role in the filling process.

Copyright 2018 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: conveyor belt, depositor, design engineer, filling pastry, food industry, food manufacturing, food manufacturing plant, jelly depositor, piston pump, positive displacement pump

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on A Jelly Depositor is a Positive Displacement Pump

Sunday, May 26th, 2013

|

We’ve been discussing hurtles which must be jumped in order for an inventor’s creation to be considered for a patent. Federal statutes, namely 35 USC § 101, define the bases of patentability, including providing definitions on key terms, such as what constitutes a machine, an article of manufacture, and a composition of matter. Today we’ll wrap up our discussion on determining patent eligibility when we explore the final hurtle by defining process.

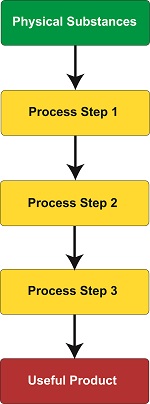

To get an understanding of what is meant by process, we must look to the lawsuit of Gottschalk v. Benson, a case involving patentability of a mathematical algorithm within a computer program. In this case the US Supreme Court held that a process is a series of steps or operations that transform substances or came about by way of a newly invented machine.

Based on the Court’s definition, a process can be many things, from a production line that transforms corn into corn chips within a food manufacturing plant to a mathematical algorithm running within software on the platform of a newly devised type of computer. However, the term usually pertains to a series of operations or steps, most frequently manufacturing in nature, where physical substances are transformed into useful products, that is, they possess the quality of utility, as discussed earlier in this blog series. A “physical substance” is anything of a physical nature existing on our planet.

Before I end this series I’d like to mention that under 35 USC § 101 an invention can be eligible for a patent if it makes a useful and beneficial improvement to an existing machine, article of manufacture, composition of matter, or process. That is to say, something may have already been patented which performs a specific function, but if that is improved upon in any significant way, it may receive a new patent.

For example, suppose an improved process for manufacturing food products was developed by adding additional steps to an existing patented process. If this improvement results in benefits such as lowered production costs, increased production rate, or reduced health risks to consumers, then this improved process may be eligible for a patent under 35 USC § 101.

Next time we’ll begin an exploration of the growing presence of 3D animations within the courtroom, specifically how they bring static 2D patent drawings to life.

___________________________________________

|

Tags: 35 USC § 101, 35 USC Section 101, 3D animations, article of manufacture, composition of matter, engineering expert witness, food manufacturing, food manufacturing plant, food processing, forensic engineer, health risks to consumers, lawsuit, machine, patent eligibility, patent infringement, patented process, process, process improvement, production costs, production rate, Title 35, useful article

Posted in Courtroom Visual Aids, Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Product Liability, Professional Malpractice | Comments Off on Determining Patent Eligibility – Part 7, Process

Sunday, November 20th, 2011

| My daughter’s boy friend stayed for dinner recently and was impressed with our after-dinner cleanup. He watched as each of us carried out our individual assigned tasks, my wife putting away leftovers and condiments, my daughter rinsing and stacking plates into the dishwasher, and me at the sink hand washing. To him we seemed a model of efficiency. It didn’t take long to return the kitchen to its usual state of pristine evening cleanliness. “Our kitchen is always a mess,” he complained, “probably because we’re so disorganized.”

You can imagine what would happen if a food manufacturing plant operated like a disorganized household kitchen. Although employees may know they are responsible for delivering safe products to consumers, without the right procedures in place an unsafe chaotic mess may result. To get everyone moving in the right direction we look to guidelines established in HACCP Design Principle No. 6.

Principle 6: Establish procedures for ensuring the HACCP system is working as intended. – In large part this Principle acts as a report card. It follows up on the guidelines established in Principles l through 5, organizing activities into written procedures.

For example, design engineers must routinely analyze important identified stages within a design project, then write procedures, that is, a step-by-step instruction guide, which encompasses them. In this way personnel involved in the design process make best use of the safeguards put in place by HACCP Design Principles 1 through 5. These steps include things like preparing design proposals, analyzing risks and hazards, creating preliminary designs, conducting design reviews, building prototype equipment and tooling, running tests, collecting test data, and analyzing test results. For each step, responsibilities of key individuals involved must be clearly defined and sequentially ordered.

But writing department procedures is only part of Principle 6. Procedures are no good if they’re just thrown into a file cabinet and no one ever looks at them. What good are guidelines without a full understanding of how to use them? Training may be necessary, and management must decide what form that educational process takes to be most effective.

Engineering management must verify that established procedures are adequate to the task. This typically involves taking a hard look at finished design projects and checking critical factors. Was an adequate risk analysis performed? Were sufficient critical control points established and critical limits monitored for effectiveness?

Next time we’ll wrap up our discussion on HACCP Design Principles by examining No. 7. It’s the last of the Principles and it’s concerned with establishing record keeping procedures.

____________________________________________

|

Tags: CCP, critical control point, critical limits, department procedures, engineering expert witness, food contamination, food equipment design, food hazard, food manufacturing, food manufacturing plant, food production line, food safety, forensic engineer, HACCP, HACCP design principle, Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability, Professional Malpractice | Comments Off on Food Manufacturing Challenges – HACCP Design Principle No. 6

Sunday, September 18th, 2011

| Some people just have a knack in the kitchen, and my wife is among them. She transforms raw ingredients into the most amazing culinary delights, almost like she’s waving a magic wand. The finished products are works of art, hand crafted with tender loving care, and lucky me, I get to feast on them regularly!

During the course of my engineering career I’ve been employed within many industries, and at one point I made the decision to leave the electric utility industry and enter into the world of food manufacturing. I accepted the position of Plant Engineer with a wholesale manufacturer of baking ingredients and frozen pastry products. My main responsibility was the design of food manufacturing equipment and their production lines.

What I had expected to be a relatively straightforward process soon proved to be more challenging. I was no longer working with hard metal as my raw material, that is, gears, nuts, and bolts, but a whole new arena of things described by adjectives such as gooey and pastey. Engineers don’t typically create food products, and let’s face it, you probably wouldn’t want to eat anything that I cooked anyway! But an engineer working within a food manufacturing plant must act as a liaison between the worlds of engineering design and the culinary arts.

Now food manufacturers typically hire professional chefs to develop new products in their research and development (R&D) kitchens. Like my wife, they’re well qualified to produce wonderful hand-made culinary delights. The sticky part comes in when their small batch recipes and preparation techniques don’t translate smoothly to the world of mass production. When it comes to handling food, human fingers are far superior to metal machinery, and raw ingredients behave differently for each.

Herein lies much of the challenge for design engineers within the food industry. How do you design equipment and production lines to make huge quantities of food that look and taste as good as the prototype products made by hand in the R&D kitchen? Next week we’ll find out.

____________________________________________

|

Tags: bolts, electric utility, engineering expert witness, food manufacturing, food manufacturing equipment design, food manufacturing plant, food processing equipment, forensic engineer, gears, machine design, machinery, nuts, plant engineer, production line, research and development

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Food Manufacturing Challenges