|

You might have had warts on your skin. They’re formed by viruses making a new home. If you’ve ever had one, you probably didn’t like it and found it hard to get rid of. Walls often have warts, too, although you probably didn’t identify them as such. “Wall Wart” is engineering talk for the black plastic protrusions you often find attached to the exterior of a wall outlet in modern homes. If you call them anything at all, it’s most likely “AC power adapters.” A typical wall wart is shown in Figure 1. Figure 1 – A Typical Wall Wart Wall warts provide a handy, portable and easy to use conversionary power source for small electronic devices, including lamps, small appliances, and various modern day electronics. If you’re like me, you have lots of them scattered on the walls of your home and office. Most people come to use them when a need arises, say you bought a scanner for your computer. Beyond that they’re usually not given much thought, but today we’re going to explore them a bit. Suppose you’re an engineer and you’ve been asked to design an electronic product for household use. The product only requires 12 volts of direct current (DC) to operate, but you know that the typical home is wired to supply 120 volts of alternating current (AC). What can be done to rectify the discrepancy? Well, there are two distinct choices. One of the choices is to design electronic circuitry capable of converting 120 volts AC into 12 volts DC, then place it inside the product. But is this the best choice? Not really. It takes time to design custom circuitry, and doing so will add substantially to the design time and final cost of the product. This is especially true if the circuitry is produced in small quantities. Besides, if the electronic product is small, there may not be enough room inside to accommodate this type of circuitry. The smarter choice would be to buy a wall wart from another company that specializes in manufacturing them. They’re produced in huge quantities, so the cost is low. They also come in standard voltages, like 12 volts DC. And because the wall wart is external to the product housing, space inside is no longer a concern. It couldn’t be any easier or cost effective. Just plug the wall wart into your home electrical outlet, then plug in the product’s 12 volt DC cord. Done! Next time we’ll take a look at what’s going on inside your basic wall wart to see how it works. ____________________________________________

|

Archive for August, 2011

Ever Had a Wall Wart?

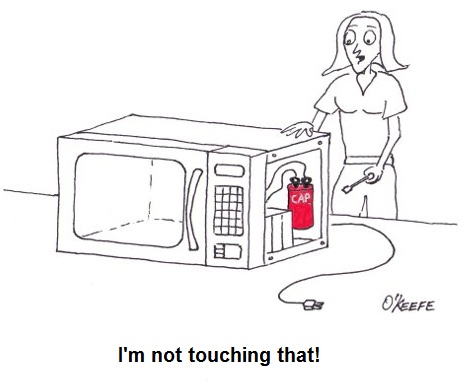

Sunday, August 28th, 2011Electrocution by Microwave Oven

Sunday, August 21st, 2011|

Ever been jolted with electric current? Like the time you’d just gotten out of the shower and went to plug in a lamp with damp hands? So what do you think the voltage was that caused that nasty biting feeling that resulted from your momentary lapse in good judgment? Once, while operating a subway car at a railroad museum at which I was a member, I was inadvertently “electrocuted.” I went to turn on the lights inside the car, and unbeknownst to me the light switch was faulty. When I touched it I instantly became connected to the car’s 600 volt lighting circuit. With just a split second of contact the current passed through the tip of my right index finger, along my right arm, down the right side of my body, and out the tip of my big toe, finally exiting into the metal railcar’s body. The current actually burned a hole where it had exited through my boot. The experience was both frightening and painful, but fortunately did not result in any real injury. I was lucky that the current had bypassed my heart, because if it hadn’t, I might not be alive today. That was 600 volts. Now imagine being jolted by the 4000 volts present in a microwave oven’s internal high voltage circuitry. Last week we discovered how the high voltage circuit in a microwave oven converts the ordinary, everyday 120 volts alternating current (AC) present in our homes into a much higher voltage approximating direct current (DC). This is done by an internal component known as the capacitor. The capacitor is capable of storing large amounts of electrical energy, and this can result in microwave ovens presenting a danger even when unplugged. A microwave oven capacitor is shown in Figure 1. If you happened to touch its wire terminals while it’s still charged, its power can rapidly discharge high voltage electrical current throughout your body. The electrical current from the capacitor can even stop your heart from beating, and this is exactly what caused the demise of a person featured on a soon to be released Discovery Channel program, Curious and Unusual Deaths. While being interviewed as an expert for the program, I was asked to explain this rather unique phenomenon of latent stored energy, and how it may present a threat. Figure 1 – A Microwave Oven Capacitor Remember, a microwave oven capacitor can remain charged with dangerous electrical energy for hours, even days, after the microwave oven plug is pulled from the wall outlet. The bottom line here is that you should not attempt to fix your microwave oven, unless you are trained and certified to do so. Next week we’ll switch to a different topic, namely an electrical device known as a “wall wart.” That’s the black plastic adapter you plug into electrical outlets to power your cell phones, laptops, and other small electronics. ____________________________________________ |

The Microwave Oven — More on How AC Becomes DC

Monday, August 15th, 2011| The world of electricity is full of mysteries and often unanticipated outcomes, and if you’ve been reading along with my blog series you have been able to appreciate and come to some understanding of a fair number of them. This week’s installment will be no exception.

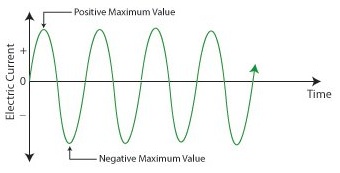

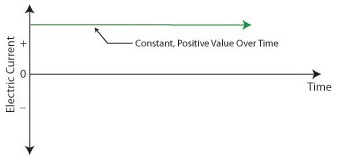

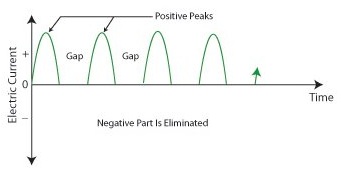

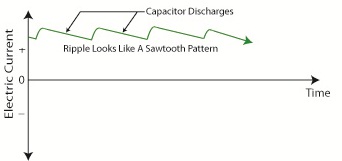

Last week we looked briefly at the high voltage circuit within a microwave oven. We discovered that the circuit contains a transformer that raises 120 volts alternating current (AC) to a much higher voltage, around 4000 volts AC. The circuit then transforms the AC into direct current (DC) with the help of electronic components known as a diode and capacitor. Let’s take a closer look at how the diode and capacitor work together to make AC into DC. Let’s follow an AC wave with the aid of a device called an oscilloscope. An oscilloscope takes in an electronic signal, measures it, graphs it, and shows it on a display screen so you can see how the signal changes over time. An AC wave is shown in Figure 1 as it would appear on an oscilloscope. Figure 1 – Alternating Current Wave You can see that each wave cycle starts with a zero value, climbs to a positive maximum value, then back to zero, and finally back down to a maximum negative value. The current keeps alternating between positive and negative polarity, hence the name “alternating current.” Within the microwave oven’s high voltage circuitry the transformer does the job of changing, or transforming if you will, 120 volts AC into 4000 volts AC. This high voltage is needed to make electrons leave the cathode in the magnetron and move them towards the anode to generate microwaves. But we’re not done with the transformation process yet. The magnetron requires DC to operate, not AC. DC current remains constant over time, maintaining a consistent positive value as shown in Figure 2. It is this type of consistency that the magnetron needs to operate. Figure 2 – Direct Current The microwave’s diode and capacitor work together to convert the 4000 volts AC into something which resembles 4000 volts DC. First the diode acts like a one-way valve, passing the flow of positive electric current and blocking the flow of negative current. It effectively chops off the negative part of the AC wave, leaving only positive peaks, as shown in Figure 3. Figure 3 – The Diode Chops Off The Negative Part of the AC Wave Between the peaks are gaps where there is zero current, and this is when the capacitor comes into play. Capacitors are similar to batteries because they can be charged with electrical energy and then discharge that energy when needed. Unlike a battery, the capacitor charges and discharges very quickly, within a fraction of a second. Within the circuitry of a microwave oven the capacitor charges up at the top of each peak in Figure 3, then, when the current drops to zero inside the gaps the capacitor comes into play, discharging its electrical energy into the high voltage circuit. The result is an elimination of the zero current gaps. The capacitor acts as a reserve energy supply to fill in the gaps between the peaks and keep current continually flowing to the magnetron. We have now witnessed a mock DC current situation being created, and the result is shown in Figure 4. Figure 4 – The Capacitor Discharges to Fill In The Gaps Between Peaks The output of this approximated DC current looks like a sawtooth pattern instead of the straight line of a true DC current shown in Figure 2. This ripple pattern is evidence of the “hoax” that has been played with the AC current. The net result is that the modified AC current, thanks to the introduction of the diode and energy storing capacitor, has made an effective enough approximation of DC current to allow our magnetron to get to work jostling electrons loose from the cathode and putting our microwave oven into action. You now have a basic understanding of how to turn AC into an effective approximation of DC current. Next week we’ll find out how this high voltage circuit can prove to be lethal, even when the microwave oven is unplugged. ____________________________________________ |

The Microwave Oven High Voltage Circuit—How AC Becomes DC

Sunday, August 7th, 2011| My mom was a female do-it-yourselfer. Toaster on the blink? Garbage disposal grind to a halt? She’d take them apart and start investigating why. Putting safety first, she always pulled the plug on electrical appliances before working on them. Little did she know that this safety precaution would not be enough in the case of a microwave oven. Let’s see how even an unplugged microwave can prove to be a lethal weapon and, yes, we’re going to have to get technical.

Last week we talked about the magnetron and how it needs thousands of volts to operate. To get this high of a voltage out of a 120 volt wall outlet–the voltage that most kitchen outlets provide–the microwave oven is equipped with electrical circuitry containing three important components: a transformer, a diode, and a capacitor, and just like the third rail of an electric railway system these items are to be avoided. If you decide to take your microwave oven apart and you come into contact with high voltage that is still present, you run the risk of injury or even death. But how can high voltage be present when it’s unplugged? Read on. First we need to understand how the 120 volts emitting from your wall outlet becomes the 4000 volts required to power a microwave’s magnetron. This change takes place thanks to a near magical act performed by AC, or alternating current. In the case of our microwave components, specifically its diode and capacitor, AC is made to effectively mimic the power of DC, or direct current, the type of current a magnetron needs. This transformation is made possible through the storage of electrical energy within the microwave’s capacitor. Next week we’ll examine in detail how this transformation from AC to DC current takes place, as seen through a device called an oscilloscope. ____________________________________________ |