| Back when television had barely escaped the confines of black and white transmission there was a men’s clothing store commercial whose slogan still sticks in my mind, “Large and small, we fit them all.” It’s a nice concept, but unfortunately the same doesn’t always apply to electronic power supplies.

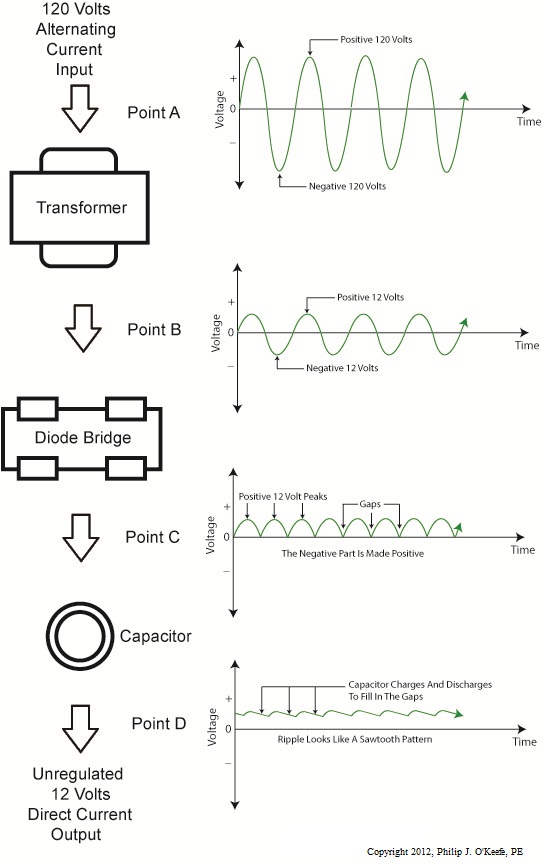

Last time we learned that when the electrical resistance changes on an unregulated power supply its output voltage changes proportionately. This makes it unsuitable for powering devices like microprocessor chips, which require an unchanging voltage to operate properly. Now let’s look at another shortcoming of unregulated power supplies, that being how one supply can’t fit both large and small voltage requirements. Figure 1 shows the components of a simple unregulated power supply. Figure 1

The diagram illustrates the voltage changes taking place as electric current passes through the supply’s four components, which ultimately results in the conversion of 120 volts alternating current (VAC) into 12 volts direct current (VDC). First the transformer converts the 120 VAC from the wall outlet to the 12 volts required by most electronic devices. These voltages are shown at Points A and B. The voltage being put out by the transformer results in waves of energy which alternate between a positive maximum value, then to zero, and finally to a maximum negative value. But we want our power supply to produce 12 VDC. By VDC, I mean voltage that never falls to zero and stays at a positive 12 volts direct current consistently. This is when the diode bridge and capacitor come into play. The diode bridge consists of four electronic components, the diodes, which are connected together to form a bridge and uses semiconductor technology to transform negative voltage from the transformer into positive. The result is a series of 12 volt peaks as shown at Point C. But we still have the problem of zero voltage gaps between each peak. You see, over time the voltage at Point C of Figure 1 keeps fluctuating between 0 volts and positive 12 volts, and this is not suitable to power most electronics, which require a steady VDC current. We can get around this problem by feeding voltage from the diode bridge into the capacitor. When we do that, we eliminate the zero voltage gaps between the peaks. This happens when the capacitor charges up with electrical energy as the voltage from the diode bridge nears the top of a peak. Then, as voltage begins its dive back to zero the capacitor discharges its electrical energy to fill in the gaps between peaks. In other words it acts as a kind of reserve battery. The result is the rippled voltage pattern observed at Point D. With the current gaps filled in, the voltage is now a steady VDC. The output voltage of the unregulated power supply is totally dependant on the design of the transformer, which in this case is designed to convert 120 volts into 12 volts. This limits the power supply’s usefulness because it can only supply one output voltage, that being 12 VDC. This voltage may be insufficient for some electronics, like those often found in microprocessor controlled devices where voltages can range between 1.5 and 24 volts. Next time we’ll illustrate this limitation by revisiting our microprocessor control circuit example and trying to fit this unregulated power supply into it. ____________________________________________ |

Posts Tagged ‘wall outlet’

Transistors – Voltage Regulation Part VII

Monday, September 3rd, 2012Ever Had a Wall Wart?

Sunday, August 28th, 2011|

You might have had warts on your skin. They’re formed by viruses making a new home. If you’ve ever had one, you probably didn’t like it and found it hard to get rid of. Walls often have warts, too, although you probably didn’t identify them as such. “Wall Wart” is engineering talk for the black plastic protrusions you often find attached to the exterior of a wall outlet in modern homes. If you call them anything at all, it’s most likely “AC power adapters.” A typical wall wart is shown in Figure 1. Figure 1 – A Typical Wall Wart Wall warts provide a handy, portable and easy to use conversionary power source for small electronic devices, including lamps, small appliances, and various modern day electronics. If you’re like me, you have lots of them scattered on the walls of your home and office. Most people come to use them when a need arises, say you bought a scanner for your computer. Beyond that they’re usually not given much thought, but today we’re going to explore them a bit. Suppose you’re an engineer and you’ve been asked to design an electronic product for household use. The product only requires 12 volts of direct current (DC) to operate, but you know that the typical home is wired to supply 120 volts of alternating current (AC). What can be done to rectify the discrepancy? Well, there are two distinct choices. One of the choices is to design electronic circuitry capable of converting 120 volts AC into 12 volts DC, then place it inside the product. But is this the best choice? Not really. It takes time to design custom circuitry, and doing so will add substantially to the design time and final cost of the product. This is especially true if the circuitry is produced in small quantities. Besides, if the electronic product is small, there may not be enough room inside to accommodate this type of circuitry. The smarter choice would be to buy a wall wart from another company that specializes in manufacturing them. They’re produced in huge quantities, so the cost is low. They also come in standard voltages, like 12 volts DC. And because the wall wart is external to the product housing, space inside is no longer a concern. It couldn’t be any easier or cost effective. Just plug the wall wart into your home electrical outlet, then plug in the product’s 12 volt DC cord. Done! Next time we’ll take a look at what’s going on inside your basic wall wart to see how it works. ____________________________________________

|

Electrocution by Microwave Oven

Sunday, August 21st, 2011|

Ever been jolted with electric current? Like the time you’d just gotten out of the shower and went to plug in a lamp with damp hands? So what do you think the voltage was that caused that nasty biting feeling that resulted from your momentary lapse in good judgment? Once, while operating a subway car at a railroad museum at which I was a member, I was inadvertently “electrocuted.” I went to turn on the lights inside the car, and unbeknownst to me the light switch was faulty. When I touched it I instantly became connected to the car’s 600 volt lighting circuit. With just a split second of contact the current passed through the tip of my right index finger, along my right arm, down the right side of my body, and out the tip of my big toe, finally exiting into the metal railcar’s body. The current actually burned a hole where it had exited through my boot. The experience was both frightening and painful, but fortunately did not result in any real injury. I was lucky that the current had bypassed my heart, because if it hadn’t, I might not be alive today. That was 600 volts. Now imagine being jolted by the 4000 volts present in a microwave oven’s internal high voltage circuitry. Last week we discovered how the high voltage circuit in a microwave oven converts the ordinary, everyday 120 volts alternating current (AC) present in our homes into a much higher voltage approximating direct current (DC). This is done by an internal component known as the capacitor. The capacitor is capable of storing large amounts of electrical energy, and this can result in microwave ovens presenting a danger even when unplugged. A microwave oven capacitor is shown in Figure 1. If you happened to touch its wire terminals while it’s still charged, its power can rapidly discharge high voltage electrical current throughout your body. The electrical current from the capacitor can even stop your heart from beating, and this is exactly what caused the demise of a person featured on a soon to be released Discovery Channel program, Curious and Unusual Deaths. While being interviewed as an expert for the program, I was asked to explain this rather unique phenomenon of latent stored energy, and how it may present a threat. Figure 1 – A Microwave Oven Capacitor Remember, a microwave oven capacitor can remain charged with dangerous electrical energy for hours, even days, after the microwave oven plug is pulled from the wall outlet. The bottom line here is that you should not attempt to fix your microwave oven, unless you are trained and certified to do so. Next week we’ll switch to a different topic, namely an electrical device known as a “wall wart.” That’s the black plastic adapter you plug into electrical outlets to power your cell phones, laptops, and other small electronics. ____________________________________________ |

GFCI Outlets and The Mighty Robot

Sunday, July 3rd, 2011Ground Fault Circuit Interrupters

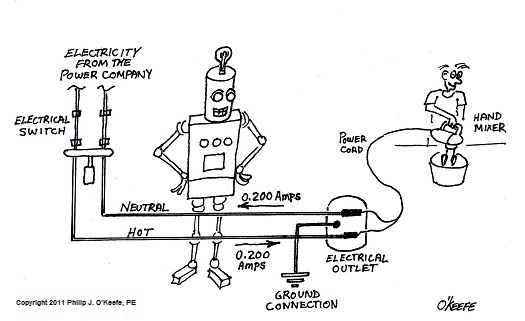

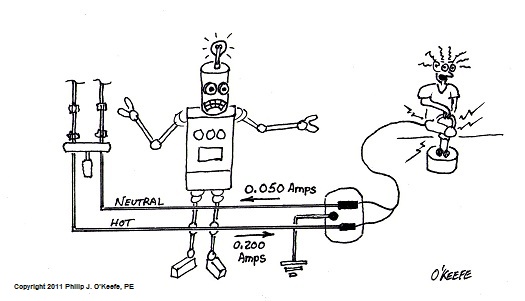

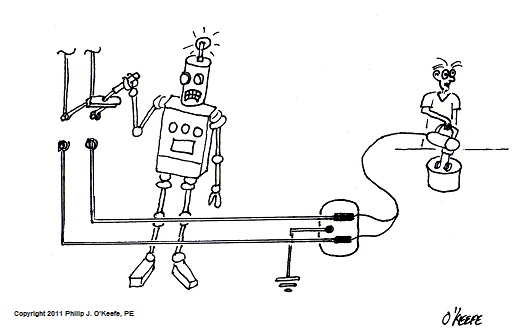

Sunday, June 26th, 2011| I’ve been talking about how I was asked to be a subject matter expert for an upcoming series on The Discovery Channel titled Curious and Unusual Deaths. Most of the accidents discussed involved electrocutions, and in each case the electrocution occurred because the victim’s body, usually their hand, inadvertently contacted a source of current. When that happened their bodies essentially became like a wire, providing an unintended path for current to travel on its way to the ground. Why does it travel to the ground, you ask? Because electric current, by its very nature, always wants to flow along a conductor of electricity from a higher voltage to a lower voltage. The ground is the lowest voltage area on our planet. When electricity flows to ground along an unintended path it’s referred to as a “ground fault,” because that’s where the electricity is headed, to the ground, or Earth. By “fault” I mean that something in an electrical circuit is broken or not right, allowing the electrical current to leak out of the circuit along an unintended path, like through a person’s body.

For example, in one of the Curious and Unusual Deaths segments I was asked to explain how a fault in wiring caused electrical current to flow through a woman’s body to the ground that she was standing on. This happened when she unintentionally came in contact with a metal door that was, unbeknownst to her, electrically charged from an unanticipated source. The current was strong enough to cause her death. Where did the electric current originate from? Watch the program to find out, but I’m sure you’d never guess. To say that it was an unlikely source is an understatement. When ground faults pass through a person’s body, bad things often happen, ranging from a stinging shock to stopping your heart muscle to burning you from the inside out. The severity depends on a number of factors, including the strength of the current to the amount of time your body is exposed to it. It might surprise you to know that if your skin is wet at the time of contacting a current, you risk a greater chance of injury. Water, from most sources, contains dissolved minerals, making it a great conductor of electricity. But what exactly is electrical current? Scientifically speaking it’s the rate of flow of electrons through a conductor of electricity. Let’s take a closer look at a subject close to home, a power cord leading from a wall’s outlet to the electric motor in your kitchen hand mixer. That power cord contains two wires. In the electrical world one wire is said to be “hot” while the other is “neutral.” The mixer whirrs away while you whip up a batch of chocolate frosting because electrons flow into its motor from the outlet through the hot wire, causing the beaters to spin. The electrons then safely flow back out of the motor to the wall outlet through the neutral wire. Now normally the number of electrons flowing into the motor through the hot wire will basically equal the number flowing out through the neutral wire, and this is a good thing. When current flow going in equals current flow going out, we end up enjoying a delicious chocolate cake. Since the human body can conduct electricity, serious consequences may result if there is an electrical defect in our hand mixer that creates a ground fault through the operator’s body while they are using it. In that situation the flow of electrons coming into the mixer from the hot wire will begin to flow through the operator’s body rather than flowing through the neutral wire. The result is that the number of electrons flowing through the hot wire does not equal the flow of electrons flowing through the neutral wire. Electrons are leaking out of what should be a closed system, entering the operator’s body instead while on its way to find the ground. Next time we’ll look at a handy device called a Ground Fault Circuit Interrupter (GFCI) and how it keeps an eye on the flow of electrons, which in turn keeps us safe from being electrocuted. _____________________________________________ |