|

We’ve been talking about coal fired power plants for some time now, and it’s always good to introduce third party information on subject matter in order to gain the most from the discussion. What follows is an excerpt of an interesting book review on the subject of coal consumption which appeared in the New York Times: There is perhaps no greater act of denial in modern life than sticking a plug into an electric outlet. No thinking person can eat a hamburger without knowing it was once a cow, or drink water from the tap without recognizing, at least dimly, that its journey began in some distant reservoir. Electricity is different. Fully sanitized of any hint of its origins, it pours out of the socket almost like magic. In his new book, Jeff Goodell breaks the spell with a single number: 20. That’s how many pounds of coal each person in the United States consumes, on average, every day to keep the electricity flowing. Despite its outdated image, coal generates half of our electricity, far more than any other source. Demand keeps rising, thanks in part to our appetite for new electronic gadgets and appliances; with nuclear power on hold and natural gas supplies tightening, coal’s importance is only going to increase. As Goodell puts it, “our shiny white iPod economy is propped up by dirty black rocks.” To read the entire article, follow this link: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/06/25/books/review/25powell.html?_r=2 A locomotive crane unloading coal from railcars at a power plant in the late 1930s. Next week we’ll continue our regular series, following energy’s journey through the power plant. _____________________________________________ |

Archive for February, 2011

Coal Power Plant Fundamentals – “Big Coal”

Sunday, February 27th, 2011Coal Power Plant Fundamentals – Combustion

Sunday, February 13th, 2011| Ever have a small child threaten to hold his breath until he passes out and he actually managed to do it? It’s not that unusual. And if his body were prevented from acting in self preservation, that is, taking in breaths while he was unconscious, leading to his eventual awakening, he would die. While the human body can survive about a month without eating and three days without water, under normal conditions it can survive only a matter of minutes without breathing. Power plants, too, require oxygen to function, and this process is called combustion.

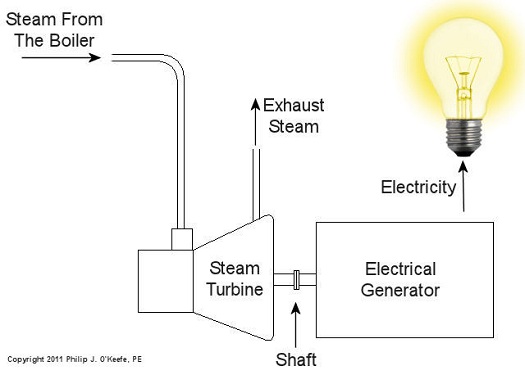

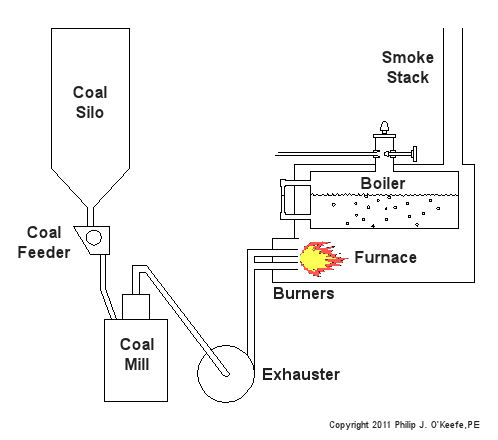

Human lungs, along with the diaphragm which works to expand and release the lung cavities, enable our bodies to breathe in air, then expel the waste product, carbon dioxide. Oxygen is needed to metabolize, that is burn, our food, enabling the food cells’ energy to be absorbed by our bodies and converted into energy to live. Like us, coal power plants need to breathe in oxygen in order to convert coal’s latent energy into a usable form. Previously we learned how coal is fed to a coal mill where it is pulverized into a fine powder. This powder is then sucked out of the mill by the exhauster and blown through a serpentine path of pipes leading to the burners on the furnace. The burners will then act upon the coal, combining it with the oxygen in our atmosphere to create a chemical reaction capable of releasing coal’s energy in the form of heat. All this activity looks to a bystander like a massive, sustained fire in the furnace. See Figure l. Figure 1 – Coal Power Plant Combustion The boiler is contained within the furnace and is situated so it is exposed to fire from the combustion process. Heat energy from the fire transfers into the water in the boiler, much like when you boil water for tea in a kettle on your stovetop. If you’ve ever boiled water, you know that once it gets hot enough it will turn into steam, and the same for our furnace boiler. The steam emitting from the boiler will cause a turbine-generator to spin, and the end result will be electricity for our use. In the simple diagram of Figure 1, waste products from the combustion process, like carbon dioxide, go up the smoke stack and are released into the atmosphere. Incidentally, this is the same type of carbon dioxide that we exhale from our bodies when we breathe. Please keep in mind that Figure 1 is a very simplified diagram. In reality waste products leaving the furnace go through various pollution control devices where most pollutants are removed before they reach the smoke stack. These details, and many more, are the type of information that would be covered during my training seminar, Coal Power Plant Fundamentals. Next time we’ll learn how the heat energy in steam is converted into mechanical energy capable of spinning a turbine generator to make electricity.

_____________________________________________ |

Coal Power Plant Fundamentals – Feeding The Furnace

Sunday, February 6th, 2011| Today we’ll continue our discussion of coal’s journey through a power plant. Keep in mind that the material presented in this series of blogs is meant to be a primer. It is a simplification of what actually goes on. My training seminars go into much more depth.

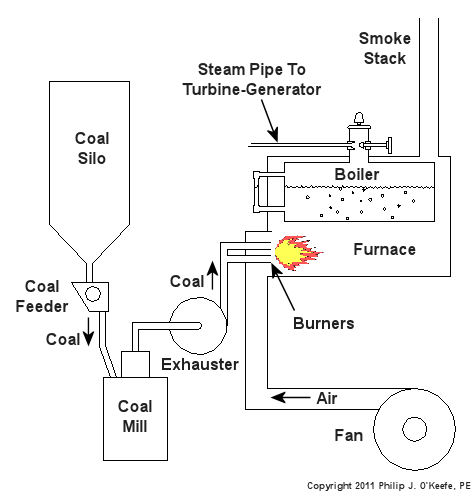

Now imagine a five course meal spread out on the table before you. You load up your plate and pack a forkful of food into your mouth. You instinctively chew, getting the digestive process underway and making it easier to swallow. Power plants approach their consumption of coal in much the same way. Last time we talked about handling the coal and filling up silos for short term storage within the power plant building. The coal silo is analogous to a dinner plate, and the furnace, which heats up the boiler water to make steam for the turbine, acts very much like a diner’s stomach. As for the fork and your teeth, there are a couple of machines within power plants which mimic their behavior. They’re called the coal feeder and coal mill. The coal feeder does as its name implies, it systematically feeds a measured amount of coal to the coal mill. The coal mill, also known as a pulverizer, then grinds the coal to make it easier for the furnace to burn it. Let’s take a look at Figure 1 below. At the top of the configuration is the coal silo, which is fully open at the bottom. Gravity draws the coal within the silo downward, facilitating the coal’s dropping through the opening into a chute, on its way to the coal feeder. The coal from the silo spills into little buckets on a wheel within the feeder, and as the wheel turns, the coal spills out and falls down into another chute leading to the mill. Figure 1 – Feeding Coal To A Power Plant Furnace Now you could have the coal spill down a chute directly from the silo into the mill, bypassing the coal feeder entirely, but that’s really not a good idea. Just think how difficult it would be to chew if you tried to stuff an entire plate of food into your mouth at once. Just as your mouth requires to be fed in mouth-sized amounts, the coal mill must be fed coal in a size that it can handle. It’s the job of the spinning wheel inside the coal feeder to keep coal flowing in measured amounts to the mill. You see, the wheel is attached to a variable speed motor, and depending on how quickly the furnace needs to be fed, the wheel will either turn faster or slower. Once inside the mill, the coal is ground up before moving on to the furnace. The coal mill contains massive steel parts capable of pulverizing chunks of coal into a fine black powder. This pulverized coal is then propelled by means of an exhauster towards the burners. The exhauster sits next to the coal mill and both are often driven by the same electric motor. The exhauster is connected to the top of the mill by a pipe, and another pipe connects the exhauster to burners on the furnace. The exhauster acts like a big vacuum cleaner, sucking coal powder out of the mill, then blowing it through pipes leading to the burners. Finally, the powder ignites within the furnace, heating the water inside the boiler. Next time we’ll learn about the combustion process in the power plant furnace. _____________________________________________ |