| Ever have a small child threaten to hold his breath until he passes out and he actually managed to do it? It’s not that unusual. And if his body were prevented from acting in self preservation, that is, taking in breaths while he was unconscious, leading to his eventual awakening, he would die. While the human body can survive about a month without eating and three days without water, under normal conditions it can survive only a matter of minutes without breathing. Power plants, too, require oxygen to function, and this process is called combustion.

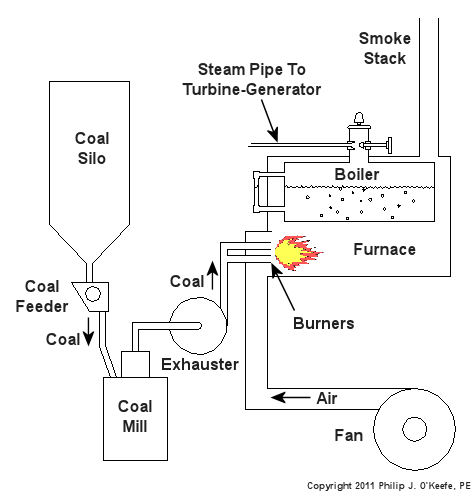

Human lungs, along with the diaphragm which works to expand and release the lung cavities, enable our bodies to breathe in air, then expel the waste product, carbon dioxide. Oxygen is needed to metabolize, that is burn, our food, enabling the food cells’ energy to be absorbed by our bodies and converted into energy to live. Like us, coal power plants need to breathe in oxygen in order to convert coal’s latent energy into a usable form. Previously we learned how coal is fed to a coal mill where it is pulverized into a fine powder. This powder is then sucked out of the mill by the exhauster and blown through a serpentine path of pipes leading to the burners on the furnace. The burners will then act upon the coal, combining it with the oxygen in our atmosphere to create a chemical reaction capable of releasing coal’s energy in the form of heat. All this activity looks to a bystander like a massive, sustained fire in the furnace. See Figure l. Figure 1 – Coal Power Plant Combustion The boiler is contained within the furnace and is situated so it is exposed to fire from the combustion process. Heat energy from the fire transfers into the water in the boiler, much like when you boil water for tea in a kettle on your stovetop. If you’ve ever boiled water, you know that once it gets hot enough it will turn into steam, and the same for our furnace boiler. The steam emitting from the boiler will cause a turbine-generator to spin, and the end result will be electricity for our use. In the simple diagram of Figure 1, waste products from the combustion process, like carbon dioxide, go up the smoke stack and are released into the atmosphere. Incidentally, this is the same type of carbon dioxide that we exhale from our bodies when we breathe. Please keep in mind that Figure 1 is a very simplified diagram. In reality waste products leaving the furnace go through various pollution control devices where most pollutants are removed before they reach the smoke stack. These details, and many more, are the type of information that would be covered during my training seminar, Coal Power Plant Fundamentals. Next time we’ll learn how the heat energy in steam is converted into mechanical energy capable of spinning a turbine generator to make electricity.

_____________________________________________ |

Posts Tagged ‘smoke stack’

Coal Power Plant Fundamentals – Combustion

Sunday, February 13th, 2011Coal Power Plant Fundamentals – Feeding The Furnace

Sunday, February 6th, 2011| Today we’ll continue our discussion of coal’s journey through a power plant. Keep in mind that the material presented in this series of blogs is meant to be a primer. It is a simplification of what actually goes on. My training seminars go into much more depth.

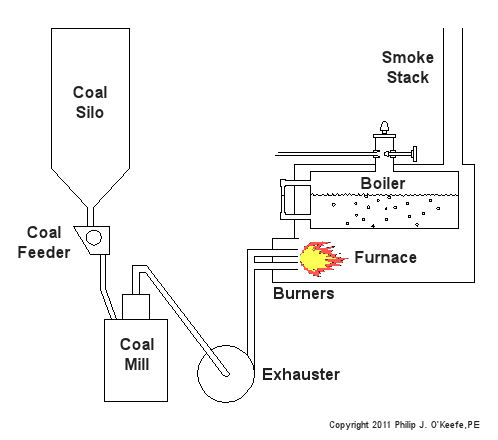

Now imagine a five course meal spread out on the table before you. You load up your plate and pack a forkful of food into your mouth. You instinctively chew, getting the digestive process underway and making it easier to swallow. Power plants approach their consumption of coal in much the same way. Last time we talked about handling the coal and filling up silos for short term storage within the power plant building. The coal silo is analogous to a dinner plate, and the furnace, which heats up the boiler water to make steam for the turbine, acts very much like a diner’s stomach. As for the fork and your teeth, there are a couple of machines within power plants which mimic their behavior. They’re called the coal feeder and coal mill. The coal feeder does as its name implies, it systematically feeds a measured amount of coal to the coal mill. The coal mill, also known as a pulverizer, then grinds the coal to make it easier for the furnace to burn it. Let’s take a look at Figure 1 below. At the top of the configuration is the coal silo, which is fully open at the bottom. Gravity draws the coal within the silo downward, facilitating the coal’s dropping through the opening into a chute, on its way to the coal feeder. The coal from the silo spills into little buckets on a wheel within the feeder, and as the wheel turns, the coal spills out and falls down into another chute leading to the mill. Figure 1 – Feeding Coal To A Power Plant Furnace Now you could have the coal spill down a chute directly from the silo into the mill, bypassing the coal feeder entirely, but that’s really not a good idea. Just think how difficult it would be to chew if you tried to stuff an entire plate of food into your mouth at once. Just as your mouth requires to be fed in mouth-sized amounts, the coal mill must be fed coal in a size that it can handle. It’s the job of the spinning wheel inside the coal feeder to keep coal flowing in measured amounts to the mill. You see, the wheel is attached to a variable speed motor, and depending on how quickly the furnace needs to be fed, the wheel will either turn faster or slower. Once inside the mill, the coal is ground up before moving on to the furnace. The coal mill contains massive steel parts capable of pulverizing chunks of coal into a fine black powder. This pulverized coal is then propelled by means of an exhauster towards the burners. The exhauster sits next to the coal mill and both are often driven by the same electric motor. The exhauster is connected to the top of the mill by a pipe, and another pipe connects the exhauster to burners on the furnace. The exhauster acts like a big vacuum cleaner, sucking coal powder out of the mill, then blowing it through pipes leading to the burners. Finally, the powder ignites within the furnace, heating the water inside the boiler. Next time we’ll learn about the combustion process in the power plant furnace. _____________________________________________ |

Coal Power Plants, Far From Perfect

Sunday, July 18th, 2010|

Did you know that even a perpetual motion machine will eventually come to a stop due to uncontrollable factors? Well, uncontrollable factors are at play in power plants, too. If you recall from our last article, heat rate is industry jargon for gauging how efficiently a coal-fired power plant is operating. We learned that heat rate can be affected by things like missing thermal insulation on pipes and equipment. Missing insulation is, of course, a thing that is under human control and easily corrected, but there are some things that affect heat rate that we just can’t do anything about. They’re called, appropriately enough, uncontrollable factors. Uncontrollable factors exist because anything devised and made by fallible humans who are beholden to the myriad laws of the universe cannot be 100 percent efficient. At their best utility coal fired power plants have an overall efficiency of between 30 and 40 percent. That means 60 to 70 percent of the energy available in the coal gets lost in the process of generating electricity. A terrible waste, right? And yet there’s nothing we can do to trim these losses until improvements in the present level of technology take place. Just as our ability to track microbes is dictated by the strength and accuracy of our magnifying equipment, so are we hampered by the tools we have at our disposal to deal with inefficiencies such as energy losses. So where does this energy get lost due to uncontrollable factors? The first and probably most obvious place to look is the smoke stack. Energy is also lost in three other ways: friction between equipment parts, auxiliary power consumption, and in a piece of equipment known as a condenser. Let’s look at each. In the most basic of terms, when coal is introduced into a power plant boiler it is combined with air and burned. This burning process releases heat energy, but it also forms gases that contain nitrogen and compounds like carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide. There’s also some water vapor formed by moisture in the coal and air. These gases and vapor absorb some of the heat energy released. To keep the combustion process going the gases and vapor must be removed from the boiler by powerful fans and sent up the smoke stack. Now, boilers are designed to absorb much of the heat energy from the gases and vapor that make their way to the stack, but they cannot possibly absorb it all. The result is that a significant amount of heat escapes up the smoke stack into the atmosphere along with the gases. Friction between parts is present everywhere in a power plant. It exists in the bearings on the shafts of motors, pumps, and steam turbines, slowing them down and hindering their operating capacity. Friction also exists where moving water and steam are present, impeding their ability to flow through piping systems. There is even friction working against the steam as it flows through parts in the turbine. Extra energy has to be expended to overcome this friction. This is energy that could be used to generate electricity. Now at some point in your life you’ve probably heard it said, “You need money to make money,” and this is very true. It takes a certain investment of resources to produce a profit-making enterprise. This investment principle holds true for the making of electricity, too. The bottom line is you need electricity to make electricity. Specifically, you have to use significant amounts of electricity to power machinery that is essential to move coal, air, combustion gases, and water through the process of making electricity in the power plant. This is called auxiliary power. It’s the electricity siphoned off by the various pieces of equipment in a power plant in its quest to generate electrical energy to be sold to customers. Another major factor at play in uncontrollable energy losses is in a piece of equipment integral to the very function of power plants: the condenser. It comes into play when water is boiled to make steam which then travels through the turbine, spinning its electrical generator and creating electric power. Unfortunately even the most efficient of steam turbines cannot use 100% of the heat energy coming at it from the steam. You see, after steam leaves the turbine, it’s turned back into water by a condenser so it can be sent back to the boiler to be turned into steam again. One of the reasons that this is done is so that the boiler does not have to be continuously filled with fresh, purified water. Water purification is necessary to keep minerals, seaweed, fish scales, and other nasty things from clogging up and damaging the boiler and steam turbine, and purified water is not as readily available as, say, lake water. The condenser acts as a heat exchanger that is hooked up to the steam turbine exhaust. It has tubes inside of it in which cold water flows, water which is drawn in from a nearby body of water, most often a river or lake. As steam blows across the outside of the cold water tubes in the condenser, it gives up its remaining heat energy and condenses into water again, then it is returned to the boiler to repeat its journey. The river water within the tubes of the condenser flows back into the river, carrying with it the heat energy removed from the steam. That wraps up our discussion about coal power plant efficiency. Next time we’ll discuss a new topic: coal fired power plant furnace explosions. _____________________________________________ |

Fossil Fuel, From Friend to Foe

Sunday, June 27th, 2010|

Did you ever have someone you considered to be a great friend and then things suddenly went bad between you? One day you’re chums and then the magic fades, soon to disappear? Sound like some marriages you’ve heard about? Well, it wasn’t too long ago that coal was considered to be America’s affordable answer to our fuel needs. It was a friend of grand proportions, there when you needed it. It remains an abundant resource, so abundant in fact that according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) we are sitting on coal reserves so vast they can provide us with sufficient energy to get us through the next 250 years at current rates of consumption. It was for these reasons that electric utilities decided decades ago to use coal as the primary source of fuel to generate electricity, and as it stands now just over 50% of our electrical energy is generated by burning coal. So how did coal go from being friend to foe? Well, just as when you’ve known someone for awhile their “baggage” becomes more apparent, it eventually became apparent to Americans that burning coal comes with some nasty baggage of its own, known as byproducts. These unwelcome components of the burning/oxidation process were found in the plumes of smoke that billowed out of power plants’ smokestacks. So just what are these byproducts? Well, some of it is the same stuff that’s left over at the bottom of your barbecue grille after a cookout, and some of it comes with scientific names like sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitric oxide (NO), and nitrous oxide (N2O). Let’s look at these in more detail. Ash is the residue that’s left behind after coal is burned. Fly ash is a type of ash that is made up of some very light particles and it can get carried away by the hot gases coming off the fire in a power plant boiler. Some of those particles manage to leave the smokestack and enter the environment. Sulfur dioxide, or SO2, is formed when the sulfur in coal combines with oxygen in the air during burning. When the SO2 leaves the smokestack, it can combine with moisture in the atmosphere to form acid rain. Most of us know what acid rain is, but for those that don’t, acid rain does things like rust metal, dissolve marble monuments, and in general disrupt the balance of Earth’s eco systems. Nitric oxide, NO, and nitrous oxide, N2O, are chemical compounds composed of nitrogen and oxygen that fall into the group commonly referred to as NOx, pronounced “knocks.” NOx is formed when nitrogen and oxygen in the air combine at the high temperatures released when coal is burned inside power plant furnaces. NOx is bad because its compounds are key ingredients in the formation of both acid rain and smog. Over the last thirty years emissions of these byproducts have come under increasing scrutiny by federal and state regulators in their quest to curb them and their impact on our environment. As a result, electric utilities have had to comply with ever-tightening regulations. To comply, coals with lower sulfur content have been used, often brought in over very long distances from mines in the US and even foreign countries like Columbia. Utilities have also been installing expensive pollution control equipment in their coal fired power plants. But these changes make operations more expensive, eating into the utilities’ profits. Now we may not like the idea of utilities earning a profit, but this is a necessary reality to some extent in order to keep their business solvent. They’re not in it for the fun of it, after all. And I’m sure you guessed by now that the net result of the regulatory agencies’ mandates is that our electric bills just keep escalating. Now much of what lies behind the current unfavorable status of coal powered plants is that when operating on our native soil they have high visibility. We don’t like to be reminded of the negatives that accompany the production of energy. Put that same plant in another faraway country and the byproducts cease to be an issue. It’s happening over there after all, and we don’t have to be confronted with it. We neglect to remind ourselves that the earth’s atmosphere is for the most part a contained unit, and that means that what happens there is happening here, whether there happens to be on the other side of the globe or not. Next week we’ll continue our explorations into coal, examining the impact of the low sulfur variety on electric utility power generation. _____________________________________________ |