| When I was a kid I remember how cool it was to have a headlight on my bike. Unlike the headlights that the other kids had, mine was not powered with flashlight batteries. The power came from a little gadget with a small wheel that rode on the front tire. As I pedaled along, the tire’s spinning caused the small wheel to spin, and voila, the headlight bulb came to life. Little did I know that this gadget was a simple form of electrical generator, and of course I was oblivious to the fact that a similar device, albeit on a much larger scale, was being used at a nearby power plant to send electricity to my home.

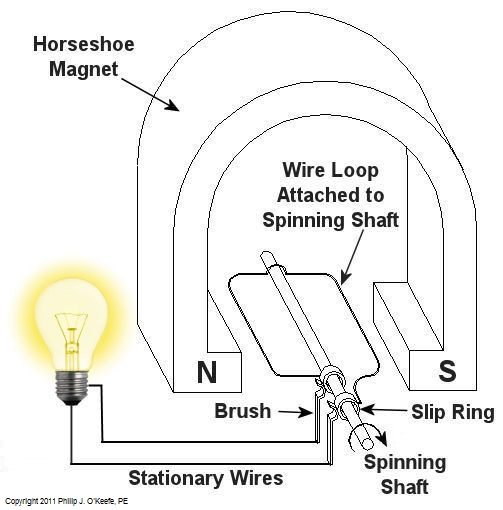

Over the last few weeks we learned how a coal fired power plant transforms chemical energy stored in coal into heat energy and then into mechanical energy which enables a steam turbine shaft to spin. We’ll now turn our attention to the electrical generator. It’s responsible for performing the last step in the energy conversion process, that is, it converts mechanical energy from the steam turbine into the desired end product, electrical energy for our use. It represents the culmination in energy’s journey through the power plant, the process by which energy contained in a lump of coal is transformed into electricity. To show how this final energy conversion process works, let’s look at Figure 1, a simplified illustration of an electrical generator. Figure 1 – A Basic Electrical Generator You’ll note that the generator in our illustration has a shaft with a loop of wire attached to it. When the shaft spins, so does the loop. The shaft and wire loop are placed between the north (N) and south (S) poles of a horseshoe magnet. It’s a permanent magnet, so it always has invisible lines of magnetic flux traveling between its two poles. These magnetic lines of flux are the same type as the ones created by kids’ magnets, when they play with watching paperclips jump up to meet the magnet. The properties of magnets are not completely understood, even to adults who work with them every day. And what could be more mysterious than the fact that as the shaft and wire loop spin through the lines of magnetic flux in the generator, an electric current is produced in the wire loop. Now, this current that’s flowing through the spinning wire loop is of no use if we can’t channel it out of the generator. The wire loop is spinning vigorously, so you can’t directly connect the ends of the loop to stationary wires. A special treatment is required. Each end of the loop is connected to a slip ring. A part called a “brush” presses against each slip ring to make electrical contact. The electrical current then flows from the loop through the spinning slip rings, through the brushes, and into the stationary wires. So, if, for example, a light bulb is connected to the other end of the stationary wires, this completes an electric circuit through which current can flow. The light bulb will glow as long as the generator shaft keeps spinning and the wire loop keeps passing through the magnetic lines of flux from the magnet. So we see that the key to the whole energy conversion process is to have movement between magnetic lines of flux and a loop of wire. As long as this movement occurs, the electricity will flow. This basic principle is the same in a coal fired power plant, but the electrical generator is far more complicated in construction and operation than shown here. My Coal Power Plant Fundamentals seminar goes into far greater detail on this and other aspects of electricity generation, but what I have shared with you above will give you a basic understanding of how they operate. That concludes our journal with coal through the power plant. This series of blogs has, you will remember, presented a simplified version of the complex material presented in my teaching seminars. Next week we’ll branch off, taking a look at why electrical wires come in different thicknesses. _____________________________________________

|

Posts Tagged ‘electricity from coal’

Coal Power Plant Fundamentals – The Generator

Monday, March 7th, 2011Fossil Fuel, From Friend to Foe

Sunday, June 27th, 2010|

Did you ever have someone you considered to be a great friend and then things suddenly went bad between you? One day you’re chums and then the magic fades, soon to disappear? Sound like some marriages you’ve heard about? Well, it wasn’t too long ago that coal was considered to be America’s affordable answer to our fuel needs. It was a friend of grand proportions, there when you needed it. It remains an abundant resource, so abundant in fact that according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) we are sitting on coal reserves so vast they can provide us with sufficient energy to get us through the next 250 years at current rates of consumption. It was for these reasons that electric utilities decided decades ago to use coal as the primary source of fuel to generate electricity, and as it stands now just over 50% of our electrical energy is generated by burning coal. So how did coal go from being friend to foe? Well, just as when you’ve known someone for awhile their “baggage” becomes more apparent, it eventually became apparent to Americans that burning coal comes with some nasty baggage of its own, known as byproducts. These unwelcome components of the burning/oxidation process were found in the plumes of smoke that billowed out of power plants’ smokestacks. So just what are these byproducts? Well, some of it is the same stuff that’s left over at the bottom of your barbecue grille after a cookout, and some of it comes with scientific names like sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitric oxide (NO), and nitrous oxide (N2O). Let’s look at these in more detail. Ash is the residue that’s left behind after coal is burned. Fly ash is a type of ash that is made up of some very light particles and it can get carried away by the hot gases coming off the fire in a power plant boiler. Some of those particles manage to leave the smokestack and enter the environment. Sulfur dioxide, or SO2, is formed when the sulfur in coal combines with oxygen in the air during burning. When the SO2 leaves the smokestack, it can combine with moisture in the atmosphere to form acid rain. Most of us know what acid rain is, but for those that don’t, acid rain does things like rust metal, dissolve marble monuments, and in general disrupt the balance of Earth’s eco systems. Nitric oxide, NO, and nitrous oxide, N2O, are chemical compounds composed of nitrogen and oxygen that fall into the group commonly referred to as NOx, pronounced “knocks.” NOx is formed when nitrogen and oxygen in the air combine at the high temperatures released when coal is burned inside power plant furnaces. NOx is bad because its compounds are key ingredients in the formation of both acid rain and smog. Over the last thirty years emissions of these byproducts have come under increasing scrutiny by federal and state regulators in their quest to curb them and their impact on our environment. As a result, electric utilities have had to comply with ever-tightening regulations. To comply, coals with lower sulfur content have been used, often brought in over very long distances from mines in the US and even foreign countries like Columbia. Utilities have also been installing expensive pollution control equipment in their coal fired power plants. But these changes make operations more expensive, eating into the utilities’ profits. Now we may not like the idea of utilities earning a profit, but this is a necessary reality to some extent in order to keep their business solvent. They’re not in it for the fun of it, after all. And I’m sure you guessed by now that the net result of the regulatory agencies’ mandates is that our electric bills just keep escalating. Now much of what lies behind the current unfavorable status of coal powered plants is that when operating on our native soil they have high visibility. We don’t like to be reminded of the negatives that accompany the production of energy. Put that same plant in another faraway country and the byproducts cease to be an issue. It’s happening over there after all, and we don’t have to be confronted with it. We neglect to remind ourselves that the earth’s atmosphere is for the most part a contained unit, and that means that what happens there is happening here, whether there happens to be on the other side of the globe or not. Next week we’ll continue our explorations into coal, examining the impact of the low sulfur variety on electric utility power generation. _____________________________________________ |