|

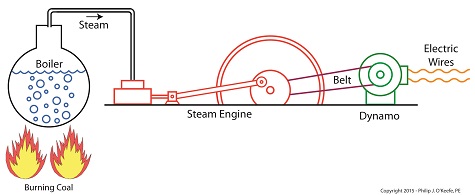

In my work as an engineering expert I’ve dealt with all forms of energy, just as we’ve watched James Prescott Joule do. He constructed his Joule Apparatus specifically to demonstrate the connection between different forms of energy. Today we’ll see how he furthered his discoveries by building a prototype power plant capable of producing electricity, a device which came to be known as Joule’s Experiment With Electricity. Joule’s Experiment With Electricity As the son of a wealthy brewer, Joule had been fascinated by electricity and the possibility of using it to power his family’s brewery and thereby boost production. To explore the possibilities, he went beyond the Apparatus he had built earlier and built a device which utilized electricity to power its components. The setup for Joule’s experiment with electricity is shown here. Coal was used to bring water inside a boiler to boiling point, which produced steam. The steam’s heat energy then flowed to a steam engine, which in turn spun a dynamo, a type of electrical generator. Tracing the device’s energy conversions back to their roots, we see that chemical energy contained within coal was converted into heat energy when the coal was burned. Heat energy from the burning coal caused the water inside the boiler to rise, producing steam. The steam, which contained abundant amounts of heat energy, was supplied to a steam engine, which then converted the steam’s heat energy into mechanical energy to set the engine’s parts into motion. The engine’s moving parts were coupled to a dynamo by a drive belt, which in turn caused the dynamo to spin. Next time we’ll take a look inside the dynamo and see how it created electricity and led to another of Joule’s discoveries being named after him. Copyright 2015 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE Engineering Expert Witness Blog ____________________________________ |

Posts Tagged ‘steam’

Joule’s Experiment With Electricity

Friday, October 16th, 2015Enthalpy Values in the Absence of a Condenser

Tuesday, November 26th, 2013|

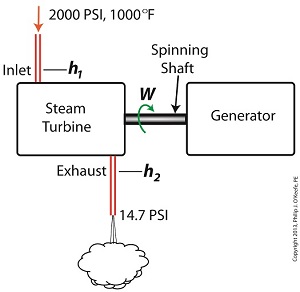

Last time we learned that the amount of useful work, W, that a steam turbine performs is calculated by taking the difference between the enthalpy of the steam entering and then leaving the turbine. And in an earlier blog we learned that a vacuum is created in the condenser when condensate is formed. This vacuum acts to lower the pressure of turbine exhaust, and in so doing also lowers the enthalpy of the exhaust steam. Putting these facts together we are able to generate data which demonstrates how the condenser increases the amount of work produced by the turbine. To better gauge the effects of a condenser, let’s look at the differences between its being present and not present. Let’s first take a look at how much work is produced by a steam turbine without a condenser. The steam entering the turbine inlet has a pressure of 2000 pounds per square inch (PSI) and a temperature of 1000°F. Knowing these turbine inlet conditions, we can go to the steam tables in any thermodynamics book to find the enthalpy, h1. Titles such as Fundamentals of Classical Thermodynamics by Gordon J. Van Wylen and Richard E. Sonntag list enthalpy values over a wide range of temperatures and pressures. For our example this volume tells us that, h1 = 1474 BTU/lb where BTU stands for British Thermal Units, a unit of measurement used to quantify the energy contained within steam or water, in our case the water to steam cycle inside a power plant. Technically speaking, a BTU is the amount of heat energy required to raise the temperature of one pound of water by one degree Fahrenheit. The term lb should be a familiar one, it’s the standard abbreviation used for pound, so enthalpy is the measurement of the amount of energy per pound of steam flowing through, in this case, the turbine. Since there is no condenser attached to the steam turbine’s exhaust in our illustration, the turbine discharges its spent steam into the surrounding atmosphere. The atmosphere in our scenario exists at 14.7 PSI because our power plant happens to be at sea level. Knowing these facts, the steam tables inform us that the value of the exhausted steam’s enthalpy, h2, is: h2 = 1015 BTU/lb Combining the two equations we are able to calculate the useful work the turbine is able to perform as: W = h1 – h2 = 1474 BTU/lb – 1015 BTU/lb = 459 BTU/lb This equation tells us that for every pound of steam flowing through it, the turbine converts 459 BTUs of the steam’s heat energy into mechanical energy to run the electrical generator. Next week we’ll connect a condenser to the steam turbine to see how its efficiency can be improved.

________________________________________ |

Boiler Feed Water, A Special Kind of Condensate

Tuesday, October 22nd, 2013|

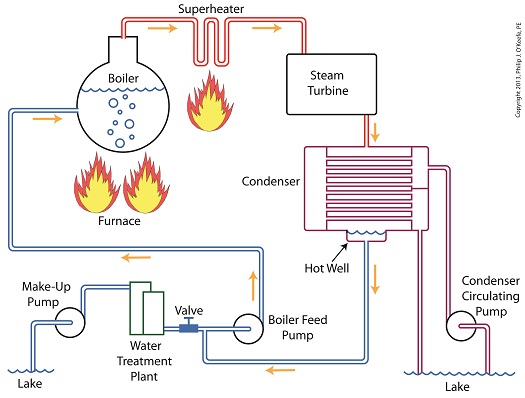

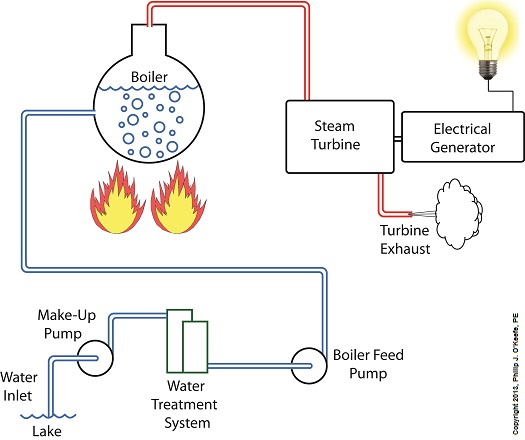

Last time we learned how the condenser within a power plant acts as a conservationist by transforming steam from the turbine exhaust back into water. This previously purified water, or condensate, contains valuable residual heat energy from its earlier journey through the power plant, making it perfect for reuse within the boiler, resulting in both water and fuel savings for the plant. Today we’ll take a look at a highly pressurized form of condensate known as boiler feed water and how it helps the power plant save money by recycling residual heat energy in the steam and water cycle. Let’s begin by integrating the condenser into the big picture, the complete water-to-steam power plant cycle, to see how it fits in. The illustration shows that both the make-up pump and the condenser circulating water pump draw water from the same supply source, in this case a lake. The circulating water pump continuously draws in water to keep the condenser tubes cool, while the make-up pump draws in water only when necessary, such as when initially filling the boiler or to make up for leaks during operation, leaks which typically occur due to worn operating parts. In a nutshell, the condenser recycles steam from the turbine exhaust for its reuse within the power plant. The journey begins when condensate drains from the hot well located at the bottom of the condenser, then gets siphoned into the boiler feed pump. If you recall from a previous article, the boiler feed pump is a powerful pump that delivers water to the boiler at high pressures, typically more than 1,500 pounds per square inch in modern power plants. After its pressure has been raised by the pump, the condensate is known as boiler feed water. The boiler feed water leaves the boiler feed pump and enters the boiler, where it will once again be transformed into steam, and the water-to-steam cycle starts all over again. That is, boiler feed water is turned to steam, it’s superheated to drive the turbine, then condenses back into condensate, and finally it’s returned to the boiler again by the boiler feed pump. Trace its journey along this closed loop by following the yellow arrows in the illustration. While you were following the arrows you may have noticed a new valve in the illustration. It’s on the pipe leading from the water treatment plant to the boiler feed pump. Next time we’ll see how this small but important item comes into play in the operation of our basic power plant steam and water cycle. ________________________________________ |

Superheater Construction and Function

Sunday, September 15th, 2013|

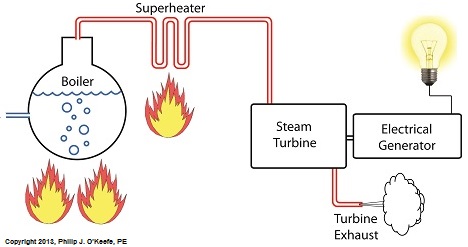

Power plants produce electrical energy for consumers to use, whether at home or for business, that’s obvious enough, but did you know that in order to produce that electrical energy they must first be supplied with heat energy? The heat energy that power plants crave comes from a fuel source, such as coal, oil, or natural gas, by way of a burning process. Once the heat energy is released from the coal through burning, it’s transported into a steam turbine by way of superheated steam, which is supplied to it by a piece of equipment named, appropriately enough, a superheater. So what is a superheater and how does it function? Take a look at the illustration below. The superheater looks like a W. It’s actually a cascading array of bent steam pipe, situated above a source of open flames which are produced by the burning of a fuel source. A photo of an actual superheater is shown below. So how many bends are in a superheater? Enough to fill the needs of the particular power plant it is supplying energy to. Since all power plants are designed differently, we’ll keep things in general terms. The many bends in the superheater’s pipes form a circuitous path for steam to flow as it follows a path from the boiler to the steam turbine. The superheater’s unique construction gives the steam flowing through it maximum exposure to heat. In other words, the bends increase the time it takes for the steam to flow through the superheater. The more bends that are present, the longer the steam will be exposed to the flame’s heat energy, and the longer that exposure, the more heat energy that is absorbed by the steam. Superheating routinely results in temperatures in excess of 1000°F. This superheated steam is laden with abundant heat energy which will keep the steam turbine spinning and the generator operating. The net result is millions of watts of electrical power. As we learned in a previous blog, the superheater is designed to provide the turbine with sensible heat energy to prevent steam from completely desuperheating, which would result in dangerous condensation inside the turbine. The newly added superheater is a major improvement to a power plant’s water-to-steam cycle, but there’s still plenty of waste and inefficiency in the system, which we’ll discuss next week.

________________________________________ |

Condensation Inside the Steam Turbine

Sunday, September 8th, 2013|

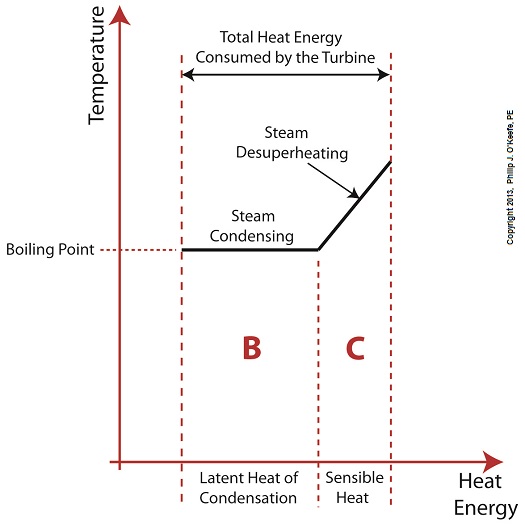

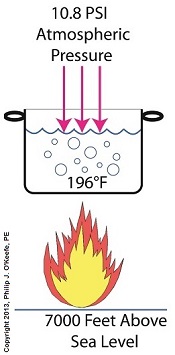

Did you know that water droplets traveling at high velocity can take on the force of bullets? It can happen, particularly within steam turbines at a power plant during the process of condensation, where steam transforms back into water. The last couple of weeks in this blog series we’ve been talking about the steam and water cycle within electric utility power plants, how heat energy is added to water during the boiling process, and how turbines run on the sensible heat energy that lies within the superheated steam vapor supplied by boilers and superheaters. We learned that without a superheater there is a very real possibility that the steam’s temperature can fall to mere boiling point. When steam returns to boiling point temperature an undesirable situation is created. The steam begins to condense into water within the turbine. To understand how this happens, let’s return to our graph from last week. It illustrates the situation when there’s no superheater present in the power plant’s steam cycle. Figure 1

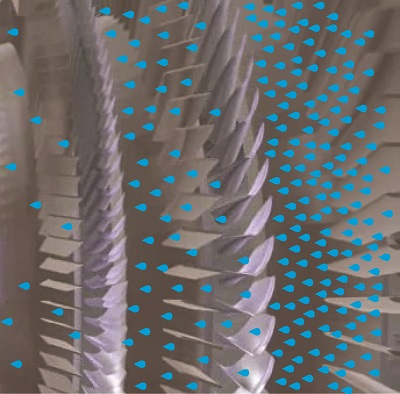

After consuming all the sensible heat energy in phase C in Figure 1, the only heat energy which remains available to the turbine is the latent heat energy in phase B. If you recall from past blog articles, latent heat energy is the energy added to the boiler water to initiate the building of steam. As the turbine consumes this final source of heat energy, the steam begins a process of condensation while it flows through the turbine. You can think of condensing as a process that is opposite to boiling. During condensation, steam changes back into water as latent heat energy is consumed by the turbine. When the condensing process is in progress, the temperature in phase B remains at boiling point, but instead of pure steam flowing through the turbine, the steam will now include water droplets, a dangerous mixture. As steam flows through the progressive chambers of turbine blades, more of its latent heat energy is consumed and increasingly more steam turns back into water as the number of water droplets increases. Figure 2 – Water Droplets Forming in the Turbine

The danger comes in when you consider that the steam/water droplet mixture is flying through the turbine at hundreds of miles per hour. At these high speeds water droplets take on the force of machine gun bullets. That’s because they act more like a solid than a liquid due to their incompressible state. In other words, under great pressure and at high speed water droplets don’t just harmlessly splash around. They hit hard and cause damage to rapidly spinning turbine blades. Without a working turbine, the generator will grind to a halt. So how do we supply the energy hungry turbine with the energy contained within high temperature superheated steam in sufficient quantities to keep things going? We’ll talk more about the superheater, its function and construction, next week.

________________________________________ |

Heat Energy Within the Power Plant— Water and Steam Cycle, Part 2

Wednesday, August 14th, 2013|

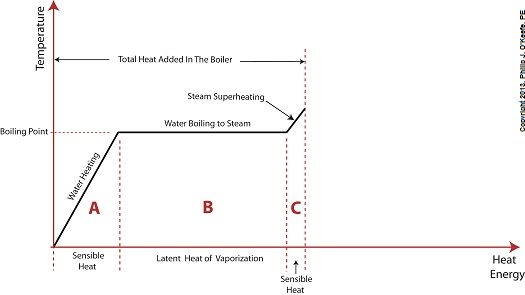

Last time we learned that electric utility power plants must have water treatment systems in place to remove contaminants from incoming feed water before it can be used. This clarified water is then fed to a boiler by the boiler feed pump as shown below. As it stands this setup will work to provide electricity, however in this state it’s both inefficient and wasteful. We’ll see why in a minute. Boilers, as their name implies, do a great job of heating water to boiling point to produce steam. They do this by adding the heat energy produced by burning fuel, such as coal, to water, then steam. We learned in earlier blogs in this series that the energy used to heat water to boiling point temperature is known as sensible heat, whereas the heat energy used to produce steam is known as latent heat. The key distinction between these two phases is that during sensible heating there is a rise in temperature, during latent heating there is not. For a review on this, see this blog article. When water starts to heat inside the boiler, sensible heat energy is said to be added. This is represented by phase A of the graph below. During A, heat energy will raise the temperature of the water to boiling point. As the water continues to boil in phase B, water is transforming into steam. During this phase latent heat energy is said to be added, and the temperature will remain at boiling point. In phase C something new takes place. The temperature rises beyond boiling point and only steam is present. This is known as superheated steam. For example, if the boiler pressure is at 1,500 pounds per square inch, steam becomes superheated at temperatures greater than 600°F. Unfortunately, boilers alone do a poor job of superheating steam, that is, continuing to raise the temperature of the steam present in phase C. This is evident by the fact that phase C is quite small in comparison to phases A and B before it. This inefficiency in producing ample amounts of superheated steam results in a small amount of useful energy being provided to the turbine down the line, which is bad, because steam turbines require exclusively superheated steam to run the generator. Next time we’ll see how to provide our steam turbine with more of what it needs to run the generator, more superheated steam. ___________________________________________

|

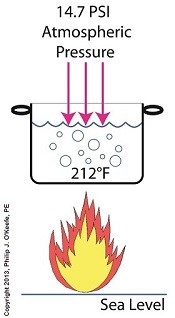

Forms of Heat Energy – Boiling Water and Atmospheric Pressure

Sunday, July 21st, 2013|

If you’ve ever baked from a pre-packaged cake or cookie mix, you’ve probably noticed the warning that baking times will vary. That’s because the elevation of the area in which you’re doing the baking makes a difference in the baking time required. Living in New Orleans? Then you’re at or below sea level. In Colorado? Then you’re above sea level. Your cake will be in the oven more or less time at the prescribed temp, depending on your location. Last time we learned how the heat energy absorbed by water determines whether it exists in one of the three states of matter, gas, liquid, or solid. We also learned that at the atmospheric pressure present at sea level, which is about 14.7 pounds per square inch (PSI), the boiling point of water is 212°F. At sea level there are 14.7 pounds of air pressure bearing down on every square inch of water surface. Again, I said sea level for a reason. The boiling point of water, just like cake batter baking times, is dependent upon the amount of pressure that’s being exerted on its surface from the surrounding atmosphere. When heat energy is absorbed, it causes the water or cake batter molecules to move around. In fact, the temperature measured is a reflection of this molecular movement. As more heat energy is absorbed, the molecules move more and more rapidly, causing temperature to increase. When the water temperature in our tea kettle reaches its boiling point of 212°F at sea level, the steam molecules in the bubbles that form have enough energy to overcome the atmospheric pressure on the surface of the water. They become airborne and escape in the form of steam. If we’re up in the Rockies at say an altitude of 7000 feet above sea level, the atmospheric pressure is only about 10.8 PSI. There’s just less air up there. That means there’s less air pressure resting upon the surface of the water, so it’s far easier for steam molecules to form into bubbles and leave the surface. As a result the boiling point is much lower in the Rockies than it is at sea level, 196°F versus 212°F. So what if the water was boiling in an environment that had even higher pressures exerted upon it than just atmospheric? We’ll see how to put this pent-up energy to good use next week, when we begin our discussion on how steam is used within electric utility power plants.

___________________________________________

|

Forms of Heat Energy – Sensible

Sunday, July 7th, 2013| In our house the whistle of a tea kettle is heard throughout the day, no matter the temp outside. So what produces that familiar high pitched sound?

When a tea kettle filled with room temperature water, say about 70°F, is heating on the stove top, the heat energy from the burner flame will transfer to the water in the kettle and its temperature will steadily rise. This heat energy that is absorbed by the water before it begins to boil is known as sensible heat in thermodynamics. To read more about thermodynamics, click on this hyperlink to one of my previous blog articles on the topic. So, why is it called sensible heat? It’s so named because it seems to make sense. The term was first used in the early 19th Century by some of the first engineers who were working on the development of boilers and steam engines to power factories and railways. Simply stated, it’s sensible to assume that the more heat you add to the water in the kettle, the more its temperature will rise. So how high will the temperature rise? Is there a point when it will cease to rise? Good questions. We’ll answer them next week, along with a discussion on another form of heat energy known as the latent heat of vaporization. ___________________________________________

|

Food Manufacturing Challenges – Cleanliness

Monday, October 3rd, 2011| My wife and I have an agreement concerning the kitchen. She cooks, I clean. Plates and utensils are easy enough to deal with, especially when you have a dishwasher. Pots and pans are a little more challenging. But what I hate the most are the food processors, mixers, blenders, slicers and dicers. They’re designed to make food preparation easier and less time consuming, but they sure don’t make the clean up any easier! Quite frankly, I suspect the time involved to clean them exceeds the time saved in food preparation.

Food processors on a larger scale are also used to manufacture many food products in manufacturing facilities, and being larger and more complicated overall, they’re even more difficult to clean. For example, I once designed a production line incorporating a dough mixer for one of the largest wholesale bakery product suppliers in the United States. A small elevator was required to lift vast amounts of ingredients into a mixing bowl the size of a compact car. Its mixing arms were so heavy, two people were required to lift them into position. It was also my task to ensure that the equipment as designed was capable of being thoroughly cleaned in a timely and cost effective manner. Food processing machinery must be designed so that all areas coming into contact with ingredients can be readily accessed for cleaning. And since most of the equipment you are dealing with in this setting is far too cumbersome to be portable, the majority of the cleaning must be cleaned in place, known in the industry as CIP. To facilitate CIP, commercial machinery is designed with hatches and special covers that allow workers to get inside with their cleaning equipment. Small, portable parts of the machine, such as pipes, cutting blades, forming mechanisms, and extrusion dies, are often made to be removable so that they can be carried over to an industrial sized sink for cleaning out of place, or COP. These potable machine components are typically removable for COP without the use of any tools and are fitted with flip latches, spring clips, and thumb screws to facilitate the process. Everything in a food manufacturing facility, from production machinery to conveyor belts, is typically cleaned with hot, pressurized water. The water is ejected from the nozzle end of a hose hooked up to a specially designed valve that mixes steam and cold water. The result is scalding hot pressurized water that easily dislodges food residues. Bacteria doesn’t stand a chance against this barrage. The water, which is maintained at about 180°F, quickly sterilizes everything it makes contact with. It also provides a chemical-free clean that won’t leave behind residues. Once dislodged, debris is flushed out through strategically placed openings in the machine which then empty into nearby floor drains. As a consequence of the frequent cleanings commercial food preparation machinery requires, their parts must be able to withstand frequent exposure to high pressure water streams. Parts are typically constructed of ultra high molecular weight (UHMW) food-grade plastics and metal alloys such as stainless steels, capable of withstanding the corrosive effects of water. And since water and electricity make a dangerous combination, gaskets and seals on the equipment must be tight enough to protect against water making its way into motors and other electrical parts. Next time we’ll look at how design engineers of food manufacturing equipment use a systematic approach to minimize the possibility of food safety hazards, such as product contamination. ____________________________________________ |