|

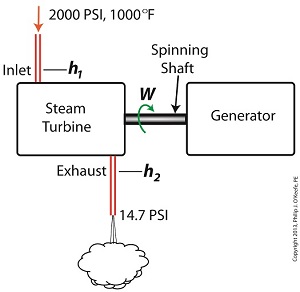

Last time we learned that the amount of useful work, W, that a steam turbine performs is calculated by taking the difference between the enthalpy of the steam entering and then leaving the turbine. And in an earlier blog we learned that a vacuum is created in the condenser when condensate is formed. This vacuum acts to lower the pressure of turbine exhaust, and in so doing also lowers the enthalpy of the exhaust steam. Putting these facts together we are able to generate data which demonstrates how the condenser increases the amount of work produced by the turbine. To better gauge the effects of a condenser, let’s look at the differences between its being present and not present. Let’s first take a look at how much work is produced by a steam turbine without a condenser. The steam entering the turbine inlet has a pressure of 2000 pounds per square inch (PSI) and a temperature of 1000°F. Knowing these turbine inlet conditions, we can go to the steam tables in any thermodynamics book to find the enthalpy, h1. Titles such as Fundamentals of Classical Thermodynamics by Gordon J. Van Wylen and Richard E. Sonntag list enthalpy values over a wide range of temperatures and pressures. For our example this volume tells us that, h1 = 1474 BTU/lb where BTU stands for British Thermal Units, a unit of measurement used to quantify the energy contained within steam or water, in our case the water to steam cycle inside a power plant. Technically speaking, a BTU is the amount of heat energy required to raise the temperature of one pound of water by one degree Fahrenheit. The term lb should be a familiar one, it’s the standard abbreviation used for pound, so enthalpy is the measurement of the amount of energy per pound of steam flowing through, in this case, the turbine. Since there is no condenser attached to the steam turbine’s exhaust in our illustration, the turbine discharges its spent steam into the surrounding atmosphere. The atmosphere in our scenario exists at 14.7 PSI because our power plant happens to be at sea level. Knowing these facts, the steam tables inform us that the value of the exhausted steam’s enthalpy, h2, is: h2 = 1015 BTU/lb Combining the two equations we are able to calculate the useful work the turbine is able to perform as: W = h1 – h2 = 1474 BTU/lb – 1015 BTU/lb = 459 BTU/lb This equation tells us that for every pound of steam flowing through it, the turbine converts 459 BTUs of the steam’s heat energy into mechanical energy to run the electrical generator. Next week we’ll connect a condenser to the steam turbine to see how its efficiency can be improved.

________________________________________ |

Posts Tagged ‘coal power plant expert’

Enthalpy Values in the Absence of a Condenser

Tuesday, November 26th, 2013Superheating, Part 2

Sunday, August 25th, 2013|

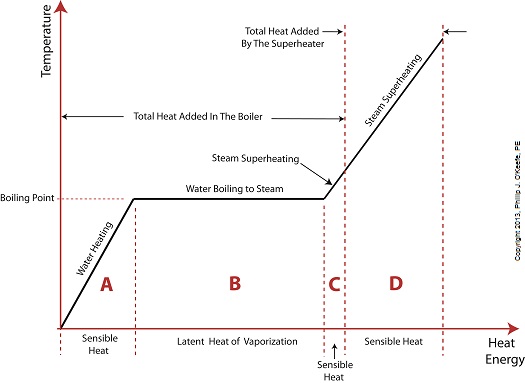

Last time we added a piece of equipment called a superheater, positioned between the boiler and steam turbine, to our basic electric utility power plant steam and water cycle. Its addition enables a greater and more consistent supply of heat energy to the steam which powers the turbine. How much more? Let’s look at Figure 1 to get an idea. Figure 1

You may have noticed that our illustration lacks numerical representation. That’s because power plants are designed differently, depending on fuels used and power output required. So unless we’re talking about a particular power plant, number values would be impractical. For example, I could specify a boiling point of 596°F at 1,500 pounds per square inch (PSI), and a superheater outlet temperature of 1,050°F at 1,200PSI, and I could make note of esoteric things like enthalpy (British Thermal Units per pound mass) values on the Heat Energy axis. But to facilitate our discussion we’ll keep things simple and focus on the general process. Figure 1 shows in phase D the additional heat energy being added to the steam, thanks to the superheater. This is significantly more than had been added by the boiler alone, as represented by phase C. The turbine consumes heat energy added in phases C and D and converts it into mechanical energy to drive the generator, resulting in electrical energy being provided to consumers in the most energy efficient way possible. But increasing power output and efficiency isn’t the superheater’s only job. The heat it adds during phase D ensures the turbine’s safe operation when it’s cranking at full capacity, as represented by the superheated steam zones of phases C and D. Next week we’ll discover how the superheater prevents a destructive process known as condensing from occurring inside the turbine. ________________________________________ |