| Imagine going on a diet and not having a scale to check your progress, or going to the doctor and not having your temperature taken. Feedback is important in our daily lives, and industry benefits by it, too.

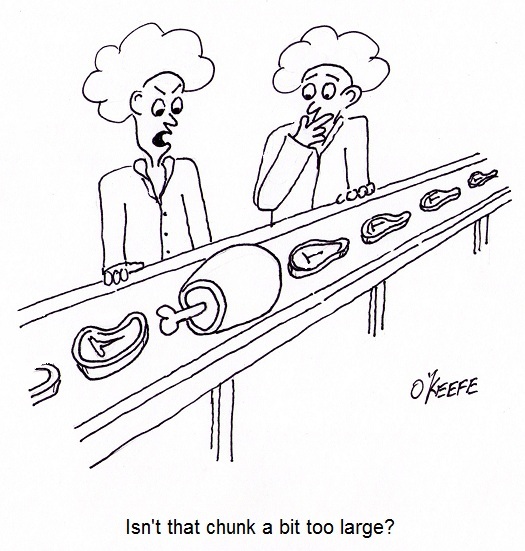

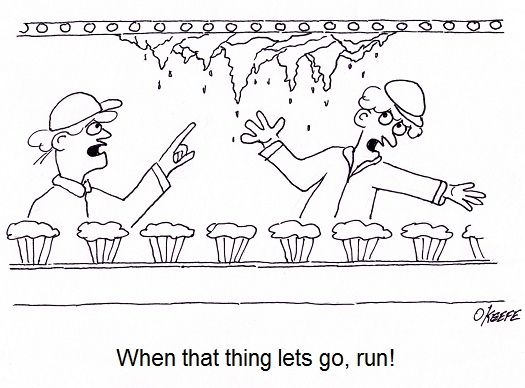

Generally speaking, feedback, or monitoring, is a tool that provides relevant information on a timely basis as to whether things are working as they were intended to. It’s an indispensable tool within the food manufacturing industry. Without it, entire plants could be erected exposing workers to injury and consumers to bacteria-laden products. It’s just plain common sense to monitor activities all along the way, starting with the design process. Now let’s see how monitoring is applied in HACCP Design Principle No. 4. Principle 4: Establish critical control point monitoring requirements. – Monitoring activities are necessary to ensure that the critical limits established at each critical control point (CCP) established under Principle 3 discussed last week are working as intended. In other words, if the engineer identifies significant risks in the design of a piece of food processing equipment and establishes critical limits at CCPs to eliminate the risk, then the CCPs must be monitored to see if the risk has actually been eliminated. Monitoring can and should be performed in food manufacturing plants by a variety of personnel, including design engineers, the manager of the engineering department, production line workers, maintenance workers, and quality control inspectors. For example, engineering department procedures in a food manufacturing plant should require the engineering manager to monitor CCPs established by the staff during the design of food processing equipment and production lines. Monitoring would include reviewing the design engineer’s plans, checking things like assumptions made concerning processes, calculations, material selections, and proposed physical dimensions. In short, monitoring should be a part of nearly every process, starting with the review of design documents, mechanical and electrical drawings, validation test data for machine prototypes, and technical specifications for mechanical and electrical components. This monitoring would be conducted by the engineering manager during all phases of the design process and before the finished equipment is turned over to the production department to start production. To illustrate, suppose the engineering manager is reviewing the logic in a programmable controller for a cooker on a production line. She discovers a problem with the lower critical limits established by her engineer at a CCP in the design of a cooker temperature control loop. You see, the time and temperature in the logic is sufficient to thoroughly cook smaller cuts of meat in most of the products that will be made on the line, however the larger cuts will be undercooked. The time and temperature settings within the logic are insufficient to account for the difference. This situation illustrates the fact that monitoring does no good unless feedback is provided with immediacy. In our example, the design engineer who first established the CCP and the critical limits was not informed in a timely manner of the difference in cooking times that different size meats would require, resulting in the writing of erroneous software logic. Fortunately, continued monitoring by the engineering manager caught the error, leading her to provide feedback about it to the design engineer, who can then make the necessary corrections to the software. Next week we’ll see what design engineers do with the feedback they’ve received, as seen through the eyes of HACCP Principle 5, covering the establishment of corrective actions. |

Posts Tagged ‘bacteria’

Food Manufacturing Challenges – HACCP Design Principle No. 4

Sunday, November 6th, 2011Food Manufacturing Challenges – HACCP Design Principle No. 3

Sunday, October 30th, 2011| How do parents make life safer and healthier for their kids? One of the ways is to impose limits on things like roaming distance within the neighborhood, curfews, and insisting that you eat your vegetables. Just common sense, right? Let’s take a look at some more of it.

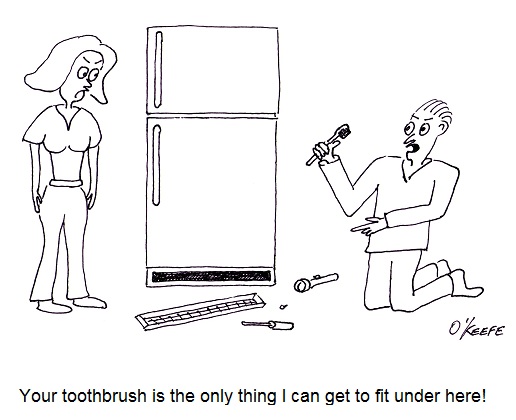

Limits are also necessary within the food manufacturing industry. Let’s take a look at Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) Principle No. 3 to see how they’re established and why. Principle 3: Establish critical limits for each critical control point. – You can think of a critical limit as a boundary of safety for each critical control point (CCP). So how do you determine that boundary of safety? It’s difficult to generalize, but if you’ve ever watched the TV show Hoarders, you have an excellent example of one that has not only been breeched, but torn asunder. In order to prevent things in the commercial food industry from getting anywhere near Hoarders bad, maximum and minimum values are set in place, representing safeguards to physical, biological, and chemical parameters at play within the industry. Critical limits can be obtained from regulatory standards and guidelines, scientific literature, experimental studies, as well as information provided by consultants. These critical limits come into play with issues as varied as machine design, raw material temperatures, and overall safe processing times. How could the hoarders let things get so bad? If you listen carefully, you’ll hear bits of information that provide a clue. They’ll say it started with a few things falling to the floor which they didn’t feel like picking up and it escalated from there. Now all of us live within environments which differ as to their cleanliness, but by and large we live within space where we feel comfortable and consider to be reasonably clean. We don’t all habitually move stoves and refrigerators to clean, for example. But if we were so inclined, refrigerators do come with front access panels that are easily removed. Trouble is the space they provide access to often isn’t large enough to accommodate hands and a vacuum cleaner nozzle comfortably. You can imagine how frustrating and potentially dangerous it would be to public health to have commercial machinery that provided such limited access for cleaning. To cope with this problem design engineers institute minimum and maximum parameters, such as in the critical limit dimensions of a removable cover. Their guideline would ensure that enough space is provided so that personnel can fully access all aspects of machinery with tools for cleaning. That same cover can also have established maximum critical limits, so that dimensions aren’t too large and heavy to be manipulated by hand. Human nature being what it is, something that is too difficult to remove may be “forgotten” and parts of the machine may never get cleaned. Raw meats and many produce can contain hazards like salmonella, E. coli, and other nasty critters that are dangerous to human health. One of the ways the commercial food industry works to ensure that these contaminants aren’t unleashed on the public is to install programmable control systems into processing machinery that essentially cooks the meat at an established minimum temperature for a minimum amount of time. Utilizing this type of temperature control in conjunction with an established maximum cooking parameter for temperature and time will virtually eliminate the possibility of overcooked or burnt food products. When you buy that frozen dinner in most cases it’s completely cooked, but it’s a rarity to find it’s been burned. Another situation in which critical limits are utilized is in the maintenance of machinery, such as when they limit the number of hours a machine can be operated before it is shut down for servicing. Next week we’ll move on to Principle No. 4 and see how it establishes monitoring requirements for each CCP. ____________________________________________ |

Food Manufacturing Challenges – HACCP Design Principle No. 1

Sunday, October 16th, 2011| Imagine a doctor not washing his hands in between baby deliveries. Unbelievable but true, this was a widespread practice up until last century when infections, followed by death of newborns, was an all-too common occurrence in hospitals across the United States. It took an observant nurse to put two and two together after watching many physicians go from delivery room to delivery room, mother to mother, without washing their hands. Once hand washing in between deliveries was made mandatory, the incidence of infection and death in newborns plummeted.

Why wasn’t this simple and common sense solution instituted earlier? Was it ignorance, negligence, laziness, or a combination thereof that kept doctors from washing up? Whatever the root cause of this ridiculous oversight, it remains a fact of history. Common sense was finally employed, and babies’ lives saved. The same common sense is at play in the development of the FDA’s Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) policy, which was developed to ensure the safe production of commercial food products. Like the observant nurse who played watchdog to doctors’ poor hygiene practices and became the catalyst for improved hospital procedures set in place and remaining until today, HACCP policy results in a proactive strategy where hazards are identified, assessed, and then control measures developed to prevent, reduce, and eliminate potential hazards. In this article, we’ll begin to explore how engineers design food processing equipment and production lines in accordance with the seven HACCP principles. You will note that here, once again, the execution of common sense can solve many problems. Principle 1: Conduct a hazard analysis. – Those involved in designing food processing equipment and production lines must proactively analyze designs to identify potential food safety hazards. If the hazard analysis reveals contaminants are likely to find their way into food products, then preventive measures are put in place in the form of design revisions. For example, suppose a food processing machine is designed and hazard analysis reveals that food can accumulate in areas where cleaning is difficult or impossible. This accumulation will rot with time, and the bacteria-laden glop can fall onto uncontaminated food passing through production lines. As another example, a piece of metal tooling may have been designed with the intent to form food products into a certain shape, but hazard analysis reveals that the tooling is too fragile and cannot withstand the repeated forces imposed on it by the mass production process. There is a strong likelihood that small metal parts can break off and enter the food on the line. Next time we’ll move on to HACCP Principle 2 and see how design engineers control problems identified during the hazard analysis performed pursuant to Principle 1. ____________________________________________ |

Food Manufacturing Challenges – Cleanliness

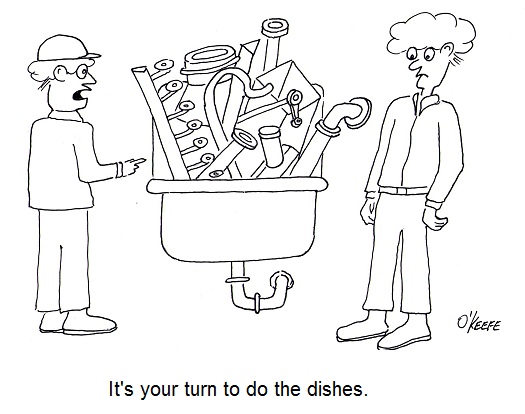

Monday, October 3rd, 2011| My wife and I have an agreement concerning the kitchen. She cooks, I clean. Plates and utensils are easy enough to deal with, especially when you have a dishwasher. Pots and pans are a little more challenging. But what I hate the most are the food processors, mixers, blenders, slicers and dicers. They’re designed to make food preparation easier and less time consuming, but they sure don’t make the clean up any easier! Quite frankly, I suspect the time involved to clean them exceeds the time saved in food preparation.

Food processors on a larger scale are also used to manufacture many food products in manufacturing facilities, and being larger and more complicated overall, they’re even more difficult to clean. For example, I once designed a production line incorporating a dough mixer for one of the largest wholesale bakery product suppliers in the United States. A small elevator was required to lift vast amounts of ingredients into a mixing bowl the size of a compact car. Its mixing arms were so heavy, two people were required to lift them into position. It was also my task to ensure that the equipment as designed was capable of being thoroughly cleaned in a timely and cost effective manner. Food processing machinery must be designed so that all areas coming into contact with ingredients can be readily accessed for cleaning. And since most of the equipment you are dealing with in this setting is far too cumbersome to be portable, the majority of the cleaning must be cleaned in place, known in the industry as CIP. To facilitate CIP, commercial machinery is designed with hatches and special covers that allow workers to get inside with their cleaning equipment. Small, portable parts of the machine, such as pipes, cutting blades, forming mechanisms, and extrusion dies, are often made to be removable so that they can be carried over to an industrial sized sink for cleaning out of place, or COP. These potable machine components are typically removable for COP without the use of any tools and are fitted with flip latches, spring clips, and thumb screws to facilitate the process. Everything in a food manufacturing facility, from production machinery to conveyor belts, is typically cleaned with hot, pressurized water. The water is ejected from the nozzle end of a hose hooked up to a specially designed valve that mixes steam and cold water. The result is scalding hot pressurized water that easily dislodges food residues. Bacteria doesn’t stand a chance against this barrage. The water, which is maintained at about 180°F, quickly sterilizes everything it makes contact with. It also provides a chemical-free clean that won’t leave behind residues. Once dislodged, debris is flushed out through strategically placed openings in the machine which then empty into nearby floor drains. As a consequence of the frequent cleanings commercial food preparation machinery requires, their parts must be able to withstand frequent exposure to high pressure water streams. Parts are typically constructed of ultra high molecular weight (UHMW) food-grade plastics and metal alloys such as stainless steels, capable of withstanding the corrosive effects of water. And since water and electricity make a dangerous combination, gaskets and seals on the equipment must be tight enough to protect against water making its way into motors and other electrical parts. Next time we’ll look at how design engineers of food manufacturing equipment use a systematic approach to minimize the possibility of food safety hazards, such as product contamination. ____________________________________________ |