| Picture yourself on a highway, it’s dark out, the wind is blowing fiercely, and you’re unable to see that the pavement is accumulating icy patches. You hit one, and your car veers out of control. Luckily you drive one of the new generation of “smart” vehicles. Wheel sensors detect your predicament and immediately initiate a sequence of events to correct the situation and bring your vehicle back into control.

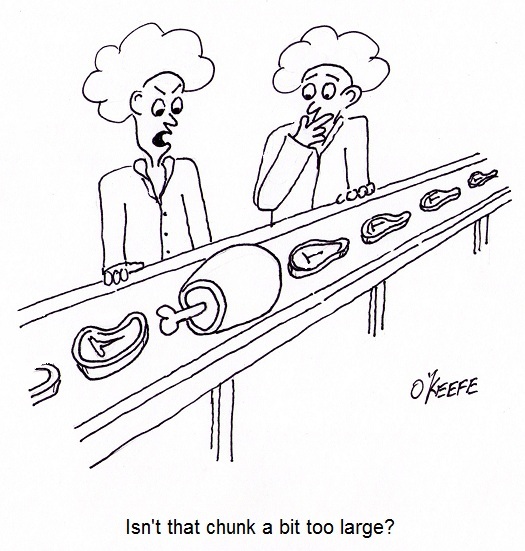

Corrective measures need to be taken in many situations when things go awry, whether they be computer-generated or human-generated corrections, and food manufacturing facilities are not exempt from the process. Let’s look at how this applies within HACCP Design Principle No. 5. Principle 5: Establish corrective actions. – Simply put, when an established critical limit at a designated critical control point (CCP) has been found not to be functioning as intended, thereby exposing consumers to potential food safety issues, design engineers must enact corrective measures to resolve the issue as soon as possible. Let’s return to the example set out in our last article, where we discussed HACCP Design Principle 4. An engineering manager has discovered a problem with the lower critical limits established by her design engineer’s software logic as it concerns a CCP established with regard to cooker temperature. The time and temperature in the logic create a hazardous situation by not taking into account that larger cuts of meat require more cooking time, resulting in them being undercooked. Fortunately, the engineering manager’s diligent and ongoing day-to-day monitoring has alerted her to the error. She immediately provides feedback about it to the design engineer, who makes corrections to the software logic. Problem solved, and all is working well within the food manufacturing plant, right? Yes, but we’re not finished. We have to make sure that a mechanism is set in place to ensure that HACCP Principles 1 through 5 are being followed and that they are actually working to protect consumers from potential food contamination hazards. Next time we’ll take a look at the last of the HACCP Design Principles, No. 6, which concerns itself with maintenance and housekeeping issues. ____________________________________________ |

Posts Tagged ‘contamination’

Food Manufacturing Challenges – HACCP Design Principle No. 5

Saturday, November 12th, 2011Food Manufacturing Challenges – HACCP Design Principle No. 4

Sunday, November 6th, 2011| Imagine going on a diet and not having a scale to check your progress, or going to the doctor and not having your temperature taken. Feedback is important in our daily lives, and industry benefits by it, too.

Generally speaking, feedback, or monitoring, is a tool that provides relevant information on a timely basis as to whether things are working as they were intended to. It’s an indispensable tool within the food manufacturing industry. Without it, entire plants could be erected exposing workers to injury and consumers to bacteria-laden products. It’s just plain common sense to monitor activities all along the way, starting with the design process. Now let’s see how monitoring is applied in HACCP Design Principle No. 4. Principle 4: Establish critical control point monitoring requirements. – Monitoring activities are necessary to ensure that the critical limits established at each critical control point (CCP) established under Principle 3 discussed last week are working as intended. In other words, if the engineer identifies significant risks in the design of a piece of food processing equipment and establishes critical limits at CCPs to eliminate the risk, then the CCPs must be monitored to see if the risk has actually been eliminated. Monitoring can and should be performed in food manufacturing plants by a variety of personnel, including design engineers, the manager of the engineering department, production line workers, maintenance workers, and quality control inspectors. For example, engineering department procedures in a food manufacturing plant should require the engineering manager to monitor CCPs established by the staff during the design of food processing equipment and production lines. Monitoring would include reviewing the design engineer’s plans, checking things like assumptions made concerning processes, calculations, material selections, and proposed physical dimensions. In short, monitoring should be a part of nearly every process, starting with the review of design documents, mechanical and electrical drawings, validation test data for machine prototypes, and technical specifications for mechanical and electrical components. This monitoring would be conducted by the engineering manager during all phases of the design process and before the finished equipment is turned over to the production department to start production. To illustrate, suppose the engineering manager is reviewing the logic in a programmable controller for a cooker on a production line. She discovers a problem with the lower critical limits established by her engineer at a CCP in the design of a cooker temperature control loop. You see, the time and temperature in the logic is sufficient to thoroughly cook smaller cuts of meat in most of the products that will be made on the line, however the larger cuts will be undercooked. The time and temperature settings within the logic are insufficient to account for the difference. This situation illustrates the fact that monitoring does no good unless feedback is provided with immediacy. In our example, the design engineer who first established the CCP and the critical limits was not informed in a timely manner of the difference in cooking times that different size meats would require, resulting in the writing of erroneous software logic. Fortunately, continued monitoring by the engineering manager caught the error, leading her to provide feedback about it to the design engineer, who can then make the necessary corrections to the software. Next week we’ll see what design engineers do with the feedback they’ve received, as seen through the eyes of HACCP Principle 5, covering the establishment of corrective actions. |

Food Manufacturing Challenges – Look and Taste

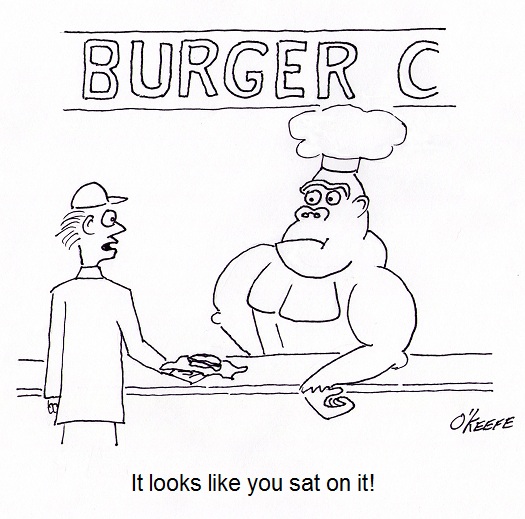

Sunday, September 25th, 2011| Ever wonder why the burger you get at your favorite fast food chain never looks like the one on TV? The bun isn’t fluffy, the beef patty doesn’t make it to the edges, and the lettuce is anything but crisp. Well, it’s because a professional known as a Food Stylist, working together with a professional marketing firm and production crew, has painstakingly created the beautiful, bright and balanced burger used to lure you in. The process can take days or even weeks to create and has nothing to do with reality. The burger you’re really going to get will look more like a gorilla sat on it.

Many of the same issues must be dealt with when mass producing food. Chances are human hands will never even touch the product, like they did when creating the prototype in the test kitchen. In the world of food manufacturing, the “look” part can be extremely challenging. How do you get machines and production lines to create visually appealing food that entices prospective buyers to make an investment in it? How do you get it to taste good, or at least acceptable to the palate? The “taste” part of food manufacturing can be even more challenging. For example, in the test kitchen of a pastry product manufacturer, a recipe will be developed using home pantry products like flour, butter, and eggs. Ever made bread or a pie crust? The stickiness factor is enough to drive many insane. Even nimble human fingers have a hard time dealing with it. Now enter food processing machinery and conveyor belts into the scenario. This brings the possibility of stickiness to a whole new level. Huge messes that gum up the machinery are common, and production line shutdowns are the result. When faced with these challenges, plant engineers have to work closely with chefs in the R&D kitchen to come up with some sort of compromise in the recipe or final form of the food product. The goal is to cost effectively produce food products acceptable to consumers for purchase, and it’s often an iterative process involving many successive changes to recipes and equipment designs, coupled with a lot of testing and retesting, before success is finally met. If testing ultimately proves that the product appeals to consumers’ tastes and flows nicely through production lines, then there’s a good chance it will be a commercial success. In any case, cost is the dictating factor as to whether the food product will successfully make it onto the shelves of your supermarket. A margin of profit must be made. But this success is only part of the design process. Before full commercial production can commence, processing equipment and production lines must be designed so that they:

Next time we’ll explore how cleanliness requirements factor into food manufacturing equipment design. ____________________________________________ |