Posts Tagged ‘microprocessor control’

Sunday, September 9th, 2012

| Back in the early 1970s my dad, a notorious tightwad, coughed up several hundred dollars to buy his first portable color television. That was a small fortune back then. The TV was massive, standing at 24 inches wide, 18 inches high, and 24 inches deep, and weighing in at about 50 pounds. I think the only thing that made this behemoth “portable” was the fact that it had a carrying handle on top.

A major reason for our old TV being so big and clunky was of course due to limitations in technology of the time. Many large, heavy, and expensive electronic components were needed to make it work, requiring a lot of space for the circuitry. By comparison, modern flat screen televisions and other electronic devices are small and compact because advances in technology enable them to work with far fewer electronic components. These components are also smaller, lighter, and cheaper.

Last time we looked at the components of a simple unregulated power supply to see how it converts 120 volts alternating current (VAC) to 12 volts direct current (VDC). We discovered that the output voltage of the supply is totally dependent on the design of the transformer, because the transformer in our example can only produce one voltage, 12 VDC. This of course limits the supply’s usefulness in that it is unable to power multiple electronic devices requiring two or more voltages, such as we’ll be discussing a bit further down.

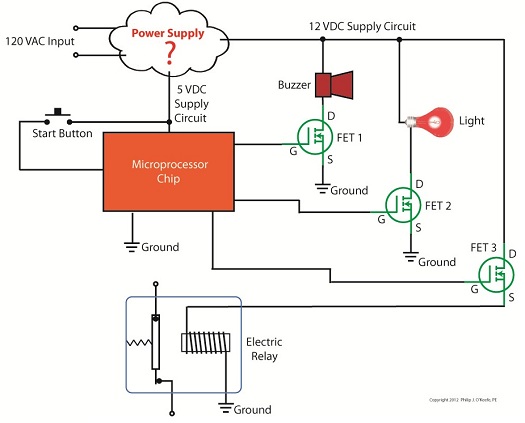

Now let’s illustrate this power supply limitation by revisiting our microprocessor control circuit example which we introduced in a previous article in this series on transistors.

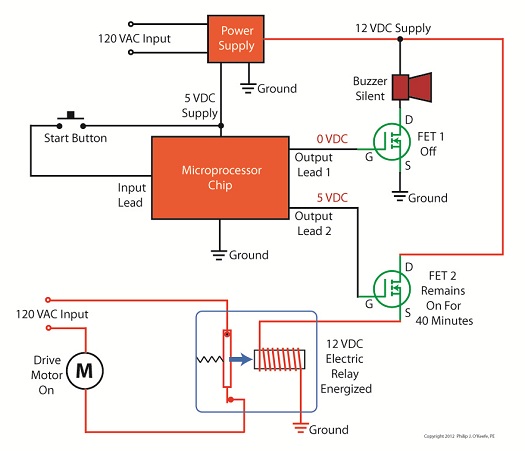

Figure 1

In Figure 1 we have to decide what kind of power to supply to the circuit, but we have a problem. Sure, the unregulated power supply that we just discussed is up to the task of providing the 12 VDC needed to supply power for the buzzer, light, and electric relay. But let’s not forget about powering the microprocessor chip. It needs only 5 VDC to operate and will get damaged and malfunction on the higher 12 VDC the current power supply provides. Our power supply just isn’t equipped to provide the two voltages required by the circuit.

We could try and get around this problem by adding a second unregulated power supply with a transformer designed to convert 120 VAC to 5 VAC. But, reminiscent of the circuitry in my dad’s clunky old portable color TV, the second power supply would require substantially more space in order to accommodate an additional transformer, diode bridge, and capacitor. Another thing to consider is that transformers aren’t cheap, and they tend to have some heft to them due to their iron cores, so more cost and weight would be added to the circuit as well. For these reasons the use of a second power supply is a poor option.

Next time we’ll look at how adding a transistor voltage regulator circuit to the supply results in cost, size, and weight savings. It also results in a more flexible and dependable output voltage.

____________________________________________ |

Tags: 12 VDC, 120 VAC, 5 VDC, buzzer, capacitor, circuit, circuitry, damage, digital logic chip, diode bridge, electric relay, electronic component, electronic device, electronics, engineering expert witness, FET, field effect transformer, forensic engineer, light, malfunction, microprocessor chip, microprocessor control, multiple voltage, power supply, television, transformer, transistor, unregulated power supply, voltage regulator, volts alternating current, volts direct current

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Transistors – Voltage Regulation Part VIII

Monday, September 3rd, 2012

| Back when television had barely escaped the confines of black and white transmission there was a men’s clothing store commercial whose slogan still sticks in my mind, “Large and small, we fit them all.” It’s a nice concept, but unfortunately the same doesn’t always apply to electronic power supplies.

Last time we learned that when the electrical resistance changes on an unregulated power supply its output voltage changes proportionately. This makes it unsuitable for powering devices like microprocessor chips, which require an unchanging voltage to operate properly. Now let’s look at another shortcoming of unregulated power supplies, that being how one supply can’t fit both large and small voltage requirements.

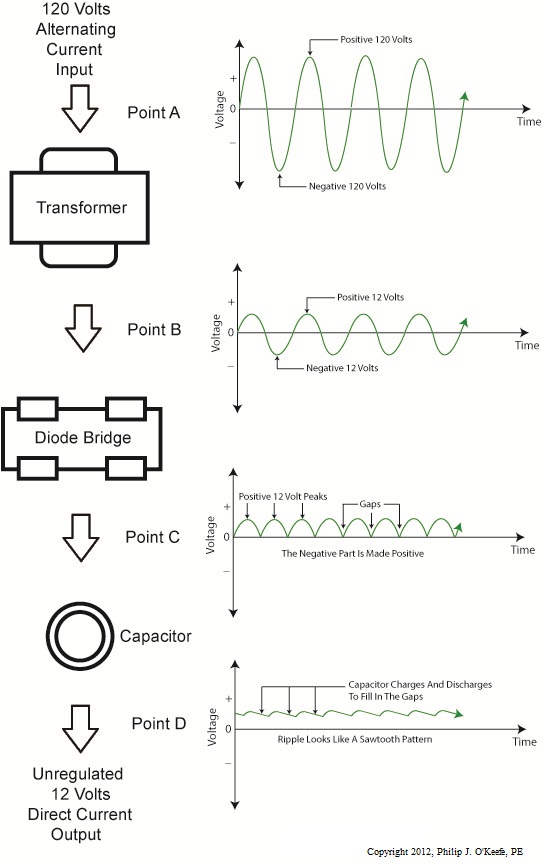

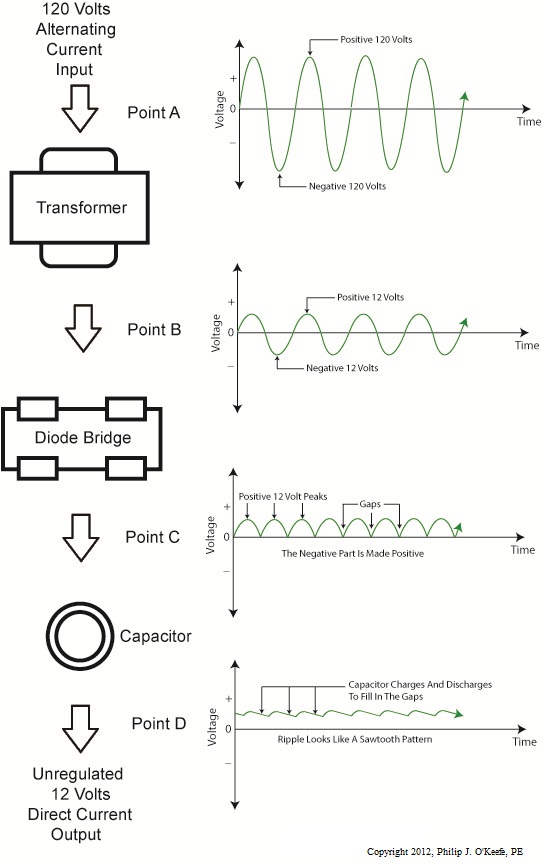

Figure 1 shows the components of a simple unregulated power supply.

Figure 1

The diagram illustrates the voltage changes taking place as electric current passes through the supply’s four components, which ultimately results in the conversion of 120 volts alternating current (VAC) into 12 volts direct current (VDC).

First the transformer converts the 120 VAC from the wall outlet to the 12 volts required by most electronic devices. These voltages are shown at Points A and B. The voltage being put out by the transformer results in waves of energy which alternate between a positive maximum value, then to zero, and finally to a maximum negative value.

But we want our power supply to produce 12 VDC. By VDC, I mean voltage that never falls to zero and stays at a positive 12 volts direct current consistently. This is when the diode bridge and capacitor come into play. The diode bridge consists of four electronic components, the diodes, which are connected together to form a bridge and uses semiconductor technology to transform negative voltage from the transformer into positive. The result is a series of 12 volt peaks as shown at Point C.

But we still have the problem of zero voltage gaps between each peak. You see, over time the voltage at Point C of Figure 1 keeps fluctuating between 0 volts and positive 12 volts, and this is not suitable to power most electronics, which require a steady VDC current.

We can get around this problem by feeding voltage from the diode bridge into the capacitor. When we do that, we eliminate the zero voltage gaps between the peaks. This happens when the capacitor charges up with electrical energy as the voltage from the diode bridge nears the top of a peak. Then, as voltage begins its dive back to zero the capacitor discharges its electrical energy to fill in the gaps between peaks. In other words it acts as a kind of reserve battery. The result is the rippled voltage pattern observed at Point D. With the current gaps filled in, the voltage is now a steady VDC.

The output voltage of the unregulated power supply is totally dependant on the design of the transformer, which in this case is designed to convert 120 volts into 12 volts. This limits the power supply’s usefulness because it can only supply one output voltage, that being 12 VDC. This voltage may be insufficient for some electronics, like those often found in microprocessor controlled devices where voltages can range between 1.5 and 24 volts.

Next time we’ll illustrate this limitation by revisiting our microprocessor control circuit example and trying to fit this unregulated power supply into it.

____________________________________________ |

Tags: battery, capacitor, current, diode, diode bridge, electrical resistance, electronic power supply, electronics, engineering expert witness, forensic engineer, microprocessor control, microprocessor control circuit, transformer, unregulated power supply, VAC, VDC, voltage, voltage regulation, volts alternating current, volts direct current, wall outlet, wave

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Transistors – Voltage Regulation Part VII

Sunday, July 29th, 2012

| I joined the Boy Scouts of America as a high schooler, mainly so I could participate in their Explorer Scout program and learn about electronics. I will forever be grateful to the Western Electric engineers who volunteered their personal time to stay after work and help me and my fellow Scouts build electronic projects. The neatest part of the whole experience was when I built my first regulated power supply with their assistance inside their lab. But in order to appreciate the beauty of a regulated power supply we must first understand the shortcomings of an unregulated one, which we’ll begin to do here.

Last time we began to discuss how the output voltage of an unregulated power supply can vary in response to power demand, just as when sprinklers don’t have sufficient water flow to cover a section of lawn. Let’s explore this concept further.

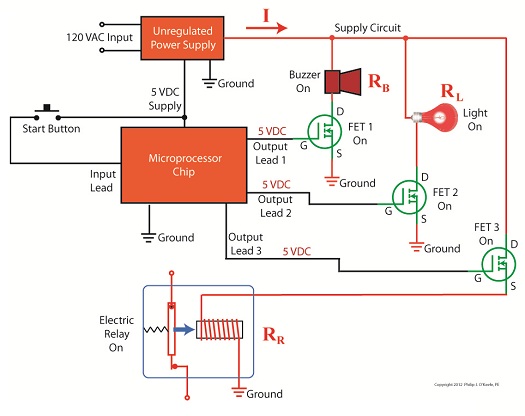

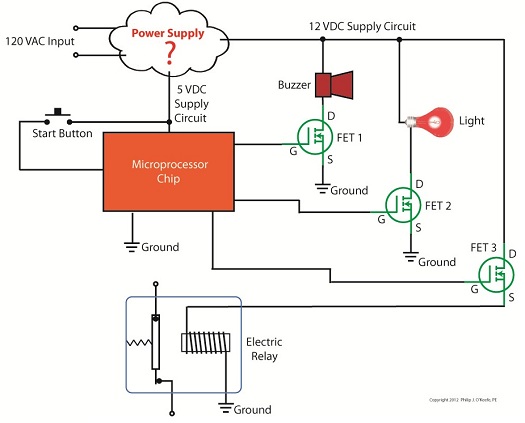

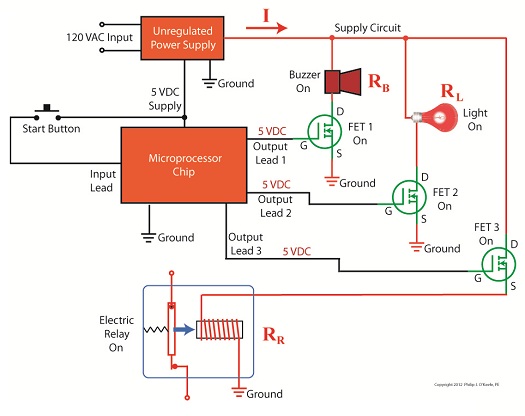

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows a very basic representation of a microprocessor control system that operates three components, an electric relay (shown in the blue box), buzzer, and light. These three components have a certain degree of internal electrical resistance, annotated as RR, RB, and RL respectively. This is because they are made of materials with inherent imperfections which tend to resist the flow of electric current. Imperfections such as these are unavoidable in any electronic device made by humans, due to impurities within metals and irregularities in molecular structure. When the three components are activated by the microprocessor chip via field effect transistors, denoted as FET 1, 2 and 3 in the diagram, their resistances are connected to the supply circuit.

In other words, RR, RB, and RL create a combined level of resistance in the supply circuit by their connectivity to it. If a single component were to be removed from the circuit, its internal resistance would also be removed, resulting in a commensurate decrease in total resistance. The greater the total resistance, the more restriction there is to current flow, denoted as I. The greater the resistance, the more I is caused to decrease. In contrast, if there is less total resistance, I increases.

The result of changing current flow resistance is that it causes the unregulated power supply output voltage to change. This is all due to an interesting phenomenon known as Ohm’s Law, represented as this within engineering circles:

V = I × R

where, V is the voltage supplied to a circuit, I is the electrical current flowing through the circuit, and R is the total electrical resistance of the circuit. So, according to Ohm’s Law, when I and R change, then V changes.

Next time we’ll apply Ohm’s Law to a simplified unregulated power supply circuit schematic. In so doing we’ll discover the mathematical explanation to the change in current flow and accompanying change in power supply output voltage we’ve been discussing.

____________________________________________ |

Tags: buzzer, current flow, electric current, electric relay, electrical component, electrical engineers, electronic device, electronic projects, electronics, engineering expert witness, FET, field effect transistor, forensic engineer, internal resistance, light, microprocessor chip, microprocessor control, Ohm's Law, output voltage varies, power supply, regulated power supply, resistance, schematic, supply circuit, unregulated power supply, voltage

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | 1 Comment »

Sunday, July 15th, 2012

| Last time we looked at my electric relay solution to a problem presented by a 120 volt alternating current (VAC) drive motor operating within an x-ray film processing machine. Now let’s see what happens when we press the button to set the microprocessor into operation.

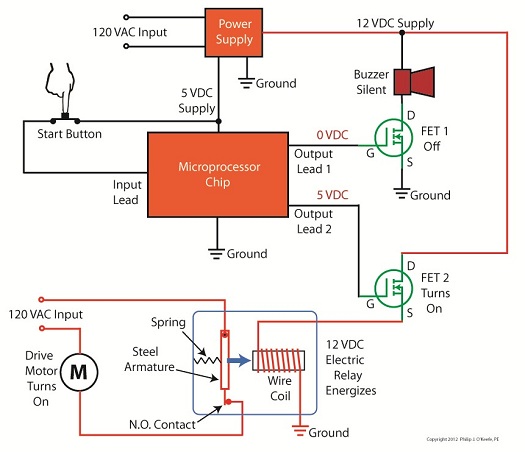

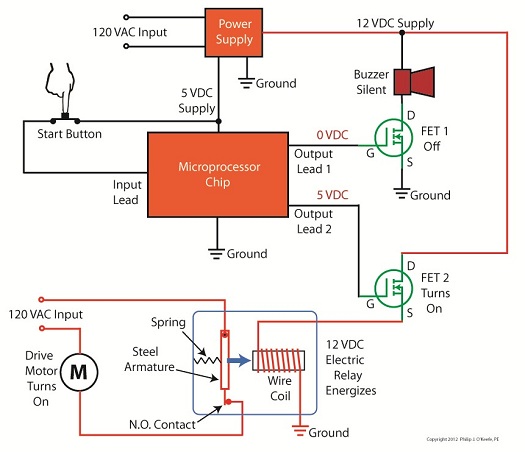

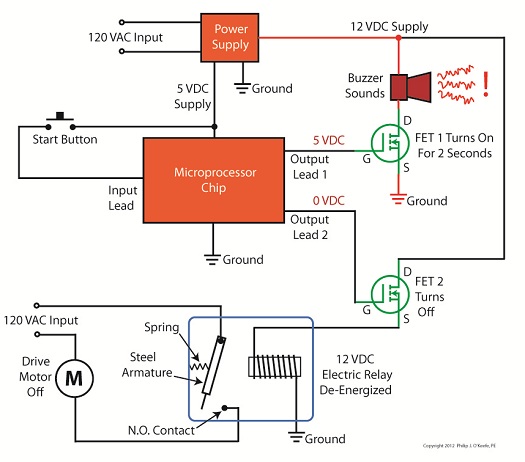

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows that when the button is depressed, the computer program contained within the microprocessor chip goes into action, signaling the start of the control initiative. 5 volts direct current (VDC) is supplied to Output Lead 2, and FET 2 (Field Effect Transistor 2) becomes activated, which allows electric current from the 12 VDC supply to course into the 12 VDC electric relay, through the relay’s wire coil, then conclude its travel into electrical ground.

The electric relay components, including a wire coil, steel armature, spring, and normally open (N.O.) contact, are shown within a blue box in our illustration. Current flow is represented by red lines. The control initiative passes from the microprocessor to FET 2, and then to the 12 VDC electric relay, just as the Olympic Torch is relayed through a system of runners.

We learned in one of my previous articles on industrial control that when an electric relay coil is energized, electromagnetic attraction pulls its steel armature towards the wire coil and the N.O. electrical contact. In Figure 1 this attraction is represented by a blue arrow. With the N.O. contact closed the drive motor is connected to the 120 VAC input, and the motor is activated.

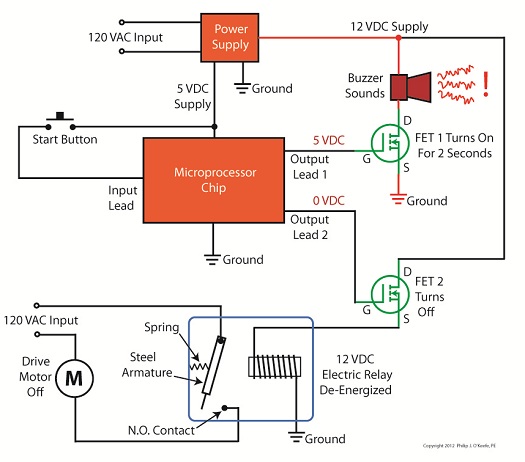

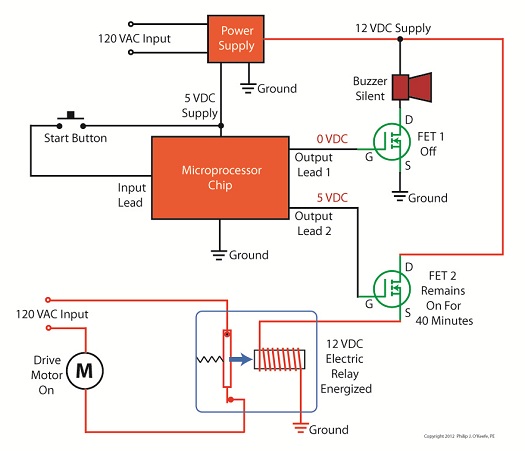

Figure 2

Figure 2 shows what happens after the button is depressed. The computer program is activated, directing the microprocessor chip to keep 5 VDC on Output Lead 2 and FET 2 while the prerequisite 40 minutes elapses. Thus the relay remains energized and the motor remains on during this time.

Figure 3

In Figure 3, at the end of the 40 minute countdown, the computer program applies 0 VDC to Output Lead 2. FET 2 then turns off the current flow to the relay and it begins to de-energize, causing the spring to pull the steel armature away from the N.O. contact and the 120 VAC power supply to be interrupted. The motor is deactivated.

At the same time, the computer program applies 5 VDC to Output Lead 1 and FET 1 for 2 seconds. FET 1 turns on the flow of current through the buzzer, causing it to sound off and signal that the x-ray film processing machine is ready for use.

Next time we’ll look at how transistors are used to regulate voltage within direct current power supplies like the one shown in Figure 3 above.

____________________________________________ |

Tags: armature, buzzer, computer program, design, electric circuit, electric drive motor, electric relay, electronic control, electronics, engineering expert witness, FET, field effect transistor, forensic engineer, industrial control, machine, microprocessor chip, microprocessor control, MOSFET, motor control, normally open contact, output lead, power supply, pushbutton, spring, transistor, voltage regulator, wire coil, x-ray film processing machine

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Transistors – Digital Control Interface, Part V

Sunday, June 24th, 2012

| Not too long ago I was retained as an engineering expert to testify on behalf of a plaintiff who owned a sports bar. The place was filled with flat screen televisions that were plugged into 120 volt alternating current (VAC) wall outlets. To make a long story short, the electric utility wires that fed power to the bar were hit by a passing vehicle, causing the voltage in the outlets to increase well beyond what the electronics in the televisions could handle. The delicate electronics were not suited to be connected with the high voltage that suddenly surged through them as a result of the hit, and they overloaded and failed.

Similarly, lower voltage microprocessor and digital logic chips are also not suited to directly connect with higher voltage devices like motors, electrical relays, and light bulbs. An interface between the two is needed to keep the delicate electronic circuits in the chips from overloading and failing like the ill fated televisions in my client’s sports bar. Let’s look now at how a field effect transistor (FET) acts as the interface between low and high voltages when put into operation within an industrial product.

I was once asked to design an industrial product, a machine which developed medical x-ray films, utilizing a microprocessor chip to automate its operation. The design requirements stated that the product be powered by a 120 VAC, such as that available through the nearest wall outlet. In terms of functionality, upon startup the microprocessor chip was to be programmed to first perform a 40-minute warmup of the machine, then activate a 12 volt direct current (VDC) buzzer for two seconds, signaling that it was ready for use. This sequence was to be initiated by a human operator depressing an activation button.

The problem presented by this scenario was that the microprocessor chip manufacturer designed it to operate on a mere 5 VDC. In additional, it was equipped with a digital output lead that was limited in functionality to either “on” or “off” and capable of only supplying either extreme of 0 VDC or 5 VDC, not the 12 VDC required by the buzzer.

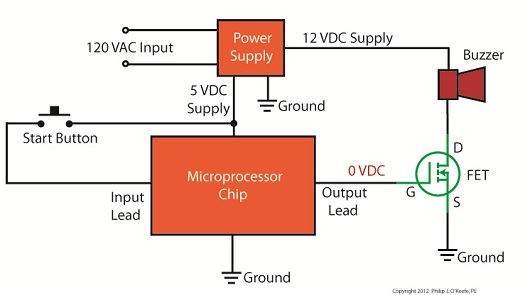

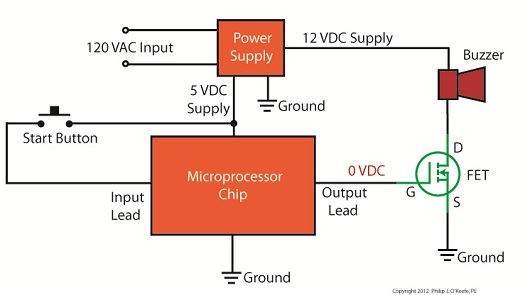

Figure 1 illustrates my solution to this voltage problem, although the diagram shown presents a highly simplified version of the end solution.

Figure 1

The illustration shows the initial power supplied at the upper left to be 120 VAC. This then is converted down to 5 VDC and 12 VDC respectively by a power supply circuit. The 5 VDC powers the microprocessor chip and the 12 VDC powers the buzzer. The conversion from high 120 VAC voltage to low 5 and 12 VDC voltage is accomplished through the use of a transformer, a diode bridge, and special transistors that regulate voltage. Since this article is about FETs, we’ll discuss transistor power supplies in more depth in a future article.

To make things a little easier to follow, the diagram in Figure 1 shows the microprocessor chip with only one input lead and one output lead. In actuality a microprocessor chip can have dozens of input and output leads, as was the case in my solution. The input leads collect information from sensors, switches, and other electrical components for processing and decision making by the computer program contained within the chip. Output leads then send out commands in the form of digital signals that are either 0 VDC or 5 VDC. In other words, off or on. The net result is that these signals are turned off or on by the program’s decision making process.

Figure 1 shows the input lead is connected to a pushbutton activated by a human. The output lead is connected to the gate (G) of the FET. The FET is shown in symbolic form in green. The FET drain (D) lead is connected to the buzzer and its source (S) lead terminates in connection to electrical ground to complete the electrical circuit. Remember, electric current naturally likes to flow from the supply source to electrical ground within circuits, and our scenario is no exception.

Next time we’ll see what happens when someone presses the button to put everything into action.

____________________________________________

|

Tags: 12 VDC, 120VAC, 5 VDC, alternating current, digital control, digital control interface, digital interface, digital logic chips, diode bridge, direct current, drain, electric ground, electric relays, electric utility, electrical circuit, electronic devices, engineering expert witness, FET, field effect transistor, forensic engineer, gate, high voltage, industrial product, input signal, light bulbs, low voltage, microprocessor control, motors, output signal, overloaded, power supply, pushbutton, source, surge, television, transformer, transistors, voltage regulator, x-ray film machine

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability, Professional Malpractice | Comments Off on Transistors – Digital Control Interface, Part II