| When my daughter was seven she found out about Ohm’s Law the hard way, although she didn’t know it. She had accidentally bumped into her electric toy train, causing its metal wheels to derail and fall askew of the metal track. This created a short circuit, causing current to flow in an undesirable direction, that is, through the derailed wheels rather than along the track to the electric motor in the locomotive as it should.

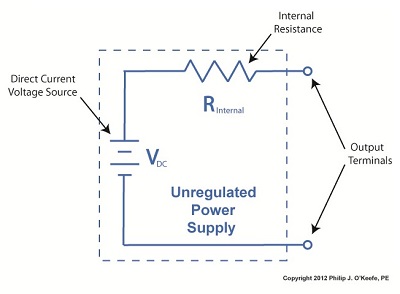

What happened during the short circuit is that the bulk of the current began to follow through the path of least resistance, that of the derailed wheels, rather than the higher resistance of the electric motor. Electric current, always opportunistic, will flow along its easiest course, in this case the short, thick metal of the wheels, rather than work its way along the many feet of thin metal wire of the motor’s electromagnetic coils. With its wheels sparking at the site of derailment the train had become an electric toaster within seconds, and the carpet beneath the track began to burn. Needless to say, mom wasn’t very happy. In this instance Ohm’s Law was at work, with a decidedly negative outcome. The Law’s basic formula concerning the toy train would be written as: I = V ÷ Rwhere, I is the current flowing through the metal track, V is the track voltage, and R is the internal resistance of the metal track and locomotive motor, or in the case of a derailment, the metal track and the derailed wheel. So, according to the formula, for a given voltage V, when the R got really small due to the derailment, I got really big. But enough about toy trains. Let’s see how Ohm’s Law applies to an unregulated power supply circuit. We’ll start with a schematic of the power supply in isolation. Figure 1The unregulated power supply shown in Figure 1 has two basic aspects to its operation, contained within a blue dashed line. The dashed line is for the sake of clarity when we connect the power supply up to an external circuit which powers peripheral devices later on. The first aspect of the power supply is a direct current (DC) voltage source, which we’ll call VDC. It’s represented by a series of parallel lines of alternating lengths, a common representation within electrical engineering. And like all electrical components, the power supply has an internal resistance, such as discussed previously. This resistance, notated RInternal, is the second aspect of the power supply, represented by another standard symbol, that of a zigzag line. Finally, the unregulated power supply has two output terminals. These will connect to an external supply circuit through which power will be provided to peripheral devices. Next time we’ll connect to this external circuit, which for our purposes will consist of an electric relay, buzzer, and light to see how it all works in accordance with Ohm’s Law. ____________________________________________ |

Posts Tagged ‘supply circuit’

Transistors – Voltage Regulation Part II

Sunday, July 29th, 2012| I joined the Boy Scouts of America as a high schooler, mainly so I could participate in their Explorer Scout program and learn about electronics. I will forever be grateful to the Western Electric engineers who volunteered their personal time to stay after work and help me and my fellow Scouts build electronic projects. The neatest part of the whole experience was when I built my first regulated power supply with their assistance inside their lab. But in order to appreciate the beauty of a regulated power supply we must first understand the shortcomings of an unregulated one, which we’ll begin to do here.

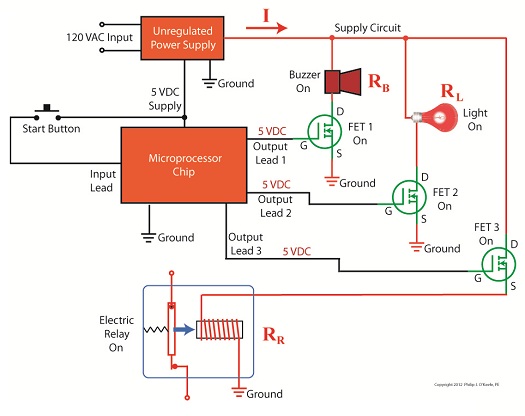

Last time we began to discuss how the output voltage of an unregulated power supply can vary in response to power demand, just as when sprinklers don’t have sufficient water flow to cover a section of lawn. Let’s explore this concept further. Figure 1

Figure 1 shows a very basic representation of a microprocessor control system that operates three components, an electric relay (shown in the blue box), buzzer, and light. These three components have a certain degree of internal electrical resistance, annotated as RR, RB, and RL respectively. This is because they are made of materials with inherent imperfections which tend to resist the flow of electric current. Imperfections such as these are unavoidable in any electronic device made by humans, due to impurities within metals and irregularities in molecular structure. When the three components are activated by the microprocessor chip via field effect transistors, denoted as FET 1, 2 and 3 in the diagram, their resistances are connected to the supply circuit. In other words, RR, RB, and RL create a combined level of resistance in the supply circuit by their connectivity to it. If a single component were to be removed from the circuit, its internal resistance would also be removed, resulting in a commensurate decrease in total resistance. The greater the total resistance, the more restriction there is to current flow, denoted as I. The greater the resistance, the more I is caused to decrease. In contrast, if there is less total resistance, I increases. The result of changing current flow resistance is that it causes the unregulated power supply output voltage to change. This is all due to an interesting phenomenon known as Ohm’s Law, represented as this within engineering circles: V = I × R where, V is the voltage supplied to a circuit, I is the electrical current flowing through the circuit, and R is the total electrical resistance of the circuit. So, according to Ohm’s Law, when I and R change, then V changes. Next time we’ll apply Ohm’s Law to a simplified unregulated power supply circuit schematic. In so doing we’ll discover the mathematical explanation to the change in current flow and accompanying change in power supply output voltage we’ve been discussing. ____________________________________________ |