| Back in the early 1970s my dad, a notorious tightwad, coughed up several hundred dollars to buy his first portable color television. That was a small fortune back then. The TV was massive, standing at 24 inches wide, 18 inches high, and 24 inches deep, and weighing in at about 50 pounds. I think the only thing that made this behemoth “portable” was the fact that it had a carrying handle on top.

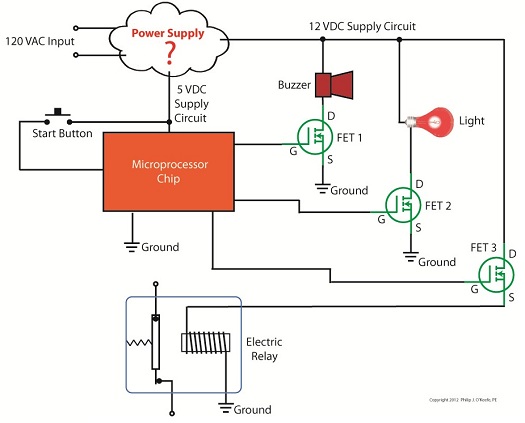

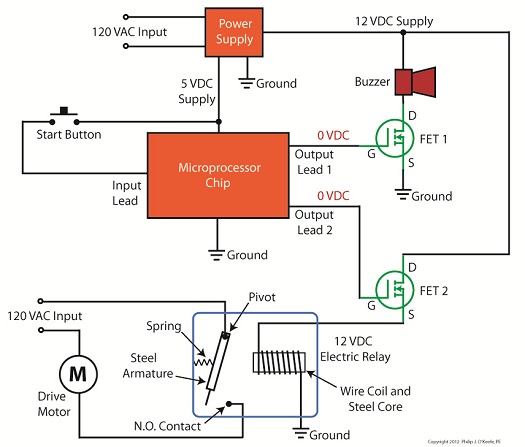

A major reason for our old TV being so big and clunky was of course due to limitations in technology of the time. Many large, heavy, and expensive electronic components were needed to make it work, requiring a lot of space for the circuitry. By comparison, modern flat screen televisions and other electronic devices are small and compact because advances in technology enable them to work with far fewer electronic components. These components are also smaller, lighter, and cheaper. Last time we looked at the components of a simple unregulated power supply to see how it converts 120 volts alternating current (VAC) to 12 volts direct current (VDC). We discovered that the output voltage of the supply is totally dependent on the design of the transformer, because the transformer in our example can only produce one voltage, 12 VDC. This of course limits the supply’s usefulness in that it is unable to power multiple electronic devices requiring two or more voltages, such as we’ll be discussing a bit further down. Now let’s illustrate this power supply limitation by revisiting our microprocessor control circuit example which we introduced in a previous article in this series on transistors. Figure 1

In Figure 1 we have to decide what kind of power to supply to the circuit, but we have a problem. Sure, the unregulated power supply that we just discussed is up to the task of providing the 12 VDC needed to supply power for the buzzer, light, and electric relay. But let’s not forget about powering the microprocessor chip. It needs only 5 VDC to operate and will get damaged and malfunction on the higher 12 VDC the current power supply provides. Our power supply just isn’t equipped to provide the two voltages required by the circuit. We could try and get around this problem by adding a second unregulated power supply with a transformer designed to convert 120 VAC to 5 VAC. But, reminiscent of the circuitry in my dad’s clunky old portable color TV, the second power supply would require substantially more space in order to accommodate an additional transformer, diode bridge, and capacitor. Another thing to consider is that transformers aren’t cheap, and they tend to have some heft to them due to their iron cores, so more cost and weight would be added to the circuit as well. For these reasons the use of a second power supply is a poor option. Next time we’ll look at how adding a transistor voltage regulator circuit to the supply results in cost, size, and weight savings. It also results in a more flexible and dependable output voltage. ____________________________________________ |

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

Published by Philip J. O'Keefe, PE, MLE