|

Without limits on our roadways things would get quickly out of hand. Imagine speeding down an unfamiliar highway and suddenly coming upon a sharp curve. With no speed limit sign to warn you to reduce speed, you could lose control of your car. Limits are useful in many situations, including within electronic circuits to keep them from getting damaged, as we’ll see in a moment.

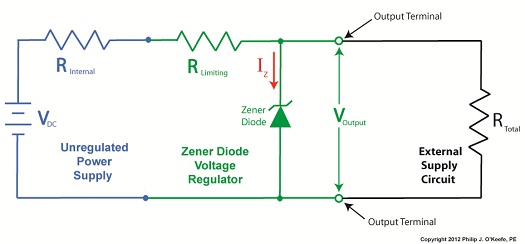

Last time we introduced the Zener diode and the fact that it performs as a voltage regulator, enabling devices connected to it to have smooth, uninterrupted operation at a constant voltage. Let’s see how it works. Figure 1

In Figure 1 we have an unregulated power supply circuit introduced in a previous article in this series. We learned that this power supply’s major shortcoming is that its output voltage, VOutput, is unregulated, in other words, it’s not constant. It varies with changes in the direct current supply voltage, VDC. It also varies with changes in, RTotal, which is the total internal resistance of components connected to it. RTotal changes when components are turned on and off by microprocessor and digital logic chips. When VOutput is not constant, those chips can malfunction, causing the device to operate erratically or not at all. But we can easily address this problem by adding a Zener diode voltage regulator between the unregulated power supply and the external supply circuit. See the green portion of Figure 2. Figure 2

Our power supply now consists of a Zener diode and a limiting resistor, RLimiting. The limiting resistor does as its name implies, it limits the amount of electric current, IZ, flowing through the Zener diode. Without this limiting resistor, IZ could get high enough to damage the diode, resulting in system failure. Next time we’ll see how the Zener diode works in tandem with the limiting resistor to control current flow and hold the output voltage at a constant level. ____________________________________________ |

Posts Tagged ‘microprocessor’

Transistors – Voltage Regulation Part XI

Monday, October 1st, 2012Transistors – Voltage Regulation Part IV

Sunday, August 12th, 2012| We’ve all popped a circuit breaker sometime in our lives, often the result of making too heavy of an electrical demand in a single area of the house to which that circuit is dedicated. Like when you’re making dinner and operating the microwave, toaster, mixer, blender, food processor, and television simultaneously. The demand for current on a single circuit can be taxed to the max, causing it to pop the circuit breaker and requiring that trip to the electrical box to flip the switch back on.

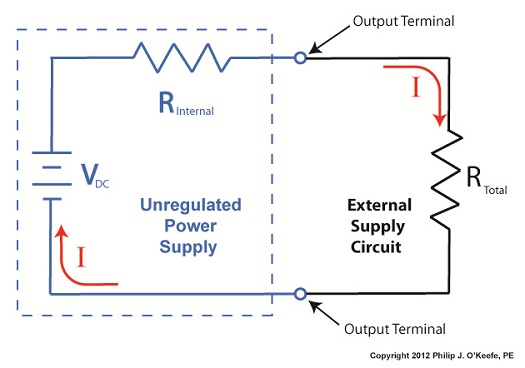

Last time we began our discussion on unregulated power supplies and how they’re affected by power demands within their circuits. Our schematic shows there are two basic aspects to the circuit, namely, its direct current source, or VDC, and its internal resistance, RInternal. Now let’s connect the power supply output terminals to an external supply circuit through which electrical current will be provided to peripheral devices, much like all the kitchen gadgets mentioned above. Figure 1

The external supply circuit shown in Figure 1 contains various electronic components, including electric relays, lights, and buzzers, and each of these has its own internal resistance. Combined, their total resistance is RTotal, as shown in our schematic. Current, notated as I, circulates through the power supply, through the external supply circuit, and then returns back to the power supply. The current circulates because the voltage, VDC, pushes it through the circuit like pressure from a pump causes water to flow through a pipe. RTotal and I can change, that is, increase or decrease, depending on how many components the microprocessor has turned on or off within the external supply circuit at any given time. When RTotal increases, electrical current, I, decreases. When RTotal decreases, electrical current I increases. Next time we’ll continue our discussion on Ohm’s Law, introduced last week, to show how the static effect of RInternal interacts with the changing resistance present in RTotal to adversely affect an unregulated power supply’s output voltage. ____________________________________________ |

Transistors – Digital Control Interface, Part I

Monday, June 18th, 2012| In the navy, the captain is the brains behind a ship’s operations. He gathers information, makes important decisions, then issues orders. He’s not there to roll up his sleeves and swab the decks. The captain relies on the ship’s officers to act as an interface between himself and the sailors that perform the physical labor required on deck.

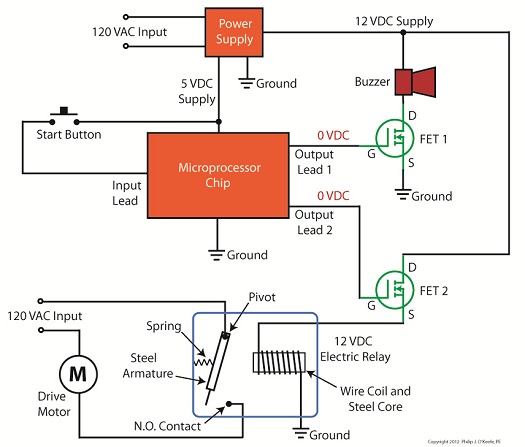

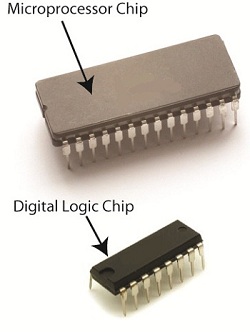

In this article we’ll see how the FET, that is, the field effect transistor, performs much the same role as the ship’s officers when it is used within electronic controls. There it acts as an interface between electronic components that issue commands and the electrical devices that carry them out. Last week we became familiar with field effect transistors and how their control of electrical current flow is analogous to how a faucet controls the flow of water. Although FETs can be used to vary the flow of current, they’re usually employed to perform a much simpler task, that of simply turning flow on or off, with no in-between modality. Like the captain of a ship, microprocessor and logic chips are the brains behind the operation in all sorts of industrial and consumer electronics. Figure 1 shows a few of them. Figure 1

The chips, which operate on low voltage, contain entire computer programs within them that gather information, make decisions, then instruct the higher voltage devices like motors, electrical relays, light bulbs, and audible alarms to follow. By “information,” I mean data signals received by the chip from its input connections to sensors, buttons, and other electrical components. This data informs the chip’s computer program of important operational information, like whether buttons have been pressed, switches are activated, and temperatures are normal. Based on this data, “decisions” are made by the chip using the logic contained within its program, then, depending on the decisions made, “commands” are issued by the chip. The commands, in the form of electrical output signals, are put into action by the work horses, the higher voltage devices. They, like a ship’s sailors, perform the actual physical work. There is one problem presented by this scenario, however. The electric output signals from the lower voltage chips are not suited to directly control the higher voltage devices because the signal voltage put out by the chips is too low. Even if the chip was designed to work at a higher voltage, the high level of current drawn by the motors, relays, and bulbs would lead to damage of the delicate circuitry within the chip. The chips must therefore rely on the FET to act as a digital control interface between them and the higher voltage devices, much as the ship’s captain depends on his subordinates to carry out his orders. Next week we’ll look at a real life example of how a digital interface is put into operation within an industrial product.

____________________________________________ |