|

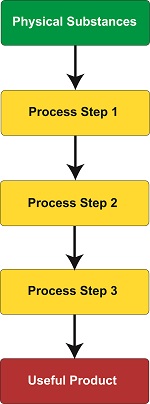

We’ve been discussing hurtles which must be jumped in order for an inventor’s creation to be considered for a patent. Federal statutes, namely 35 USC § 101, define the bases of patentability, including providing definitions on key terms, such as what constitutes a machine, an article of manufacture, and a composition of matter. Today we’ll wrap up our discussion on determining patent eligibility when we explore the final hurtle by defining process. To get an understanding of what is meant by process, we must look to the lawsuit of Gottschalk v. Benson, a case involving patentability of a mathematical algorithm within a computer program. In this case the US Supreme Court held that a process is a series of steps or operations that transform substances or came about by way of a newly invented machine. Based on the Court’s definition, a process can be many things, from a production line that transforms corn into corn chips within a food manufacturing plant to a mathematical algorithm running within software on the platform of a newly devised type of computer. However, the term usually pertains to a series of operations or steps, most frequently manufacturing in nature, where physical substances are transformed into useful products, that is, they possess the quality of utility, as discussed earlier in this blog series. A “physical substance” is anything of a physical nature existing on our planet.

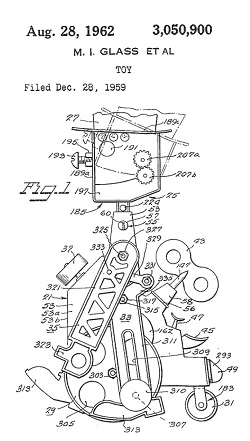

Before I end this series I’d like to mention that under 35 USC § 101 an invention can be eligible for a patent if it makes a useful and beneficial improvement to an existing machine, article of manufacture, composition of matter, or process. That is to say, something may have already been patented which performs a specific function, but if that is improved upon in any significant way, it may receive a new patent. For example, suppose an improved process for manufacturing food products was developed by adding additional steps to an existing patented process. If this improvement results in benefits such as lowered production costs, increased production rate, or reduced health risks to consumers, then this improved process may be eligible for a patent under 35 USC § 101. Next time we’ll begin an exploration of the growing presence of 3D animations within the courtroom, specifically how they bring static 2D patent drawings to life. ___________________________________________ |

Posts Tagged ‘article of manufacture’

Determining Patent Eligibility – Part 7, Process

Sunday, May 26th, 2013Determining Patent Eligibility – Part 3, What Constitutes a Machine?

Sunday, April 21st, 2013Determining Patent Eligibility – Part 1

Sunday, April 7th, 2013|

Last time I introduced the concept of intellectual property, or IP. We learned that IP in the eyes of the law is recognized as a creation of an individual inventor’s mind, worthy of commercial value. It goes to follow that those inventions that have been awarded patents are also a form of IP, because they represent the working ideation of the inventor’s mind. As such, the patent grants the inventor the sole legal right to profit from the invention to the exclusion of all others. So all you need is an idea, and you can apply for a patent, right? Well, not really. There are in fact a number of tests that potentially patentable inventions must pass. Federal laws governing patents have been in existence since 1790. They were put in place to give inventors the means to legally protect their exclusive rights to profit from their inventions in our new country. The first patent was awarded to inventor Samuel Hopkins on July 31st of that year, for a process he created to make potash, an ingredient used to make fertilizer. Since that time, the patent laws have been continually revised and expanded to improve the patenting process, something that became necessary due to the explosion of patentable technological innovations after the Industrial Revolution started in the 19th Century. In July of 1952, the basic structure of modern patent law was laid out by Title 35 of the United States Code (USC). Title 35 is a set of laws drafted by Congress that contains all federal statutes governing patents. Within Title 35 is found Section 101. It’s the part that addresses patent eligibility. This Section is commonly referred to within the trade by patent agents and attorneys as 35 USC § 101, shorthand for “Title 35 of the USC, Section 101.” According to 35 USC § 101, in order to be patentable an invention must first be useful. In addition, it must be either a machine, an article of manufacture, a composition of matter, or a process, or it must improve upon an existing machine, article of manufacture, composition, or process. But what does this all really mean? We’ll find out next time. ___________________________________________ |