|

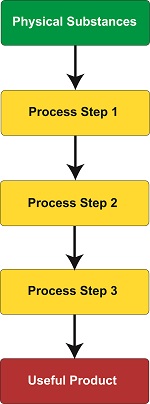

We’ve been discussing hurtles which must be jumped in order for an inventor’s creation to be considered for a patent. Federal statutes, namely 35 USC § 101, define the bases of patentability, including providing definitions on key terms, such as what constitutes a machine, an article of manufacture, and a composition of matter. Today we’ll wrap up our discussion on determining patent eligibility when we explore the final hurtle by defining process. To get an understanding of what is meant by process, we must look to the lawsuit of Gottschalk v. Benson, a case involving patentability of a mathematical algorithm within a computer program. In this case the US Supreme Court held that a process is a series of steps or operations that transform substances or came about by way of a newly invented machine. Based on the Court’s definition, a process can be many things, from a production line that transforms corn into corn chips within a food manufacturing plant to a mathematical algorithm running within software on the platform of a newly devised type of computer. However, the term usually pertains to a series of operations or steps, most frequently manufacturing in nature, where physical substances are transformed into useful products, that is, they possess the quality of utility, as discussed earlier in this blog series. A “physical substance” is anything of a physical nature existing on our planet.

Before I end this series I’d like to mention that under 35 USC § 101 an invention can be eligible for a patent if it makes a useful and beneficial improvement to an existing machine, article of manufacture, composition of matter, or process. That is to say, something may have already been patented which performs a specific function, but if that is improved upon in any significant way, it may receive a new patent. For example, suppose an improved process for manufacturing food products was developed by adding additional steps to an existing patented process. If this improvement results in benefits such as lowered production costs, increased production rate, or reduced health risks to consumers, then this improved process may be eligible for a patent under 35 USC § 101. Next time we’ll begin an exploration of the growing presence of 3D animations within the courtroom, specifically how they bring static 2D patent drawings to life. ___________________________________________ |

Posts Tagged ‘patent eligibility’

Determining Patent Eligibility – Part 7, Process

Sunday, May 26th, 2013Determining Patent Eligibility – Part 5, Manufactured Articles

Monday, May 6th, 2013|

Imagine having freshly baked pastries available to you all day long, every day, while at work. I’m not talking about someone bringing in a box of donuts to share, I’m talking about baked goods on a massive scale. This is what I experienced in one of my design engineering positions within the food industry. These baked goods constituted the articles of manufacture of the food plant, and they presented a constant temptation to me. Just what constitutes an article of manufacture is another aspect of the second hurtle which must be passed to determine patent eligibility. It is addressed under federal statutes governing the same, 35 USC § 101, and is contained within the same area as the discussion of what constitutes a machine, a subject we took up previously in this series. Why bother defining articles of manufacture? Well, while hearing the patent case of Diamond v. Chakrabarty regarding genetically engineered bacterium capable of eating crude oil, the US Supreme Court saw fit to define the term so as to resolve a conflict between the inventor and the patent office as to whether a living organism could be patented. The net result was the Court declared that in order to be deemed a patentable article of manufacture the object must be produced from either raw or man-made materials by either hand labor or machinery and must take on “new forms, qualities, properties, or combinations” that would not naturally occur without human intervention. In other words, a creation process must take place and something which did not previously exist must be caused to exist. The court’s definition of articles of manufacture encompasses an incredible array of products, much too vast to enumerate here. Suffice it to say that the defining characteristic is that if it should consist of two or more parts, there is no interaction between the parts, otherwise it could be categorized as a machine. In other words, the relationship between their parts is static, unmoving. An example would be a hammer. It’s made up of two parts, a steel head and wooden handle. These parts are firmly attached to one another, so they act as one. Next time we’ll continue our discussion on the second hurtle presented by 35 USC § 101, where we’ll discuss what is meant by composition of matter. |

Determining Patent Eligibility – Part 4, Machines of a Different Kind

Sunday, April 28th, 2013|

During 6th grade science we had a chapter on Simple Machines, and my textbook listed a common lever as an example, the sort that can be used to make work easier. Its illustration showed a stick perched atop a triangular shaped stone, appearing very much like a teeter-totter in the playground. A man was pushing down on one end of the stick to move a large boulder with the other end. Staring at it I thought to myself, “That doesn’t look like a machine to me. Where are its gears?” That day I learned about more than just levers, I learned to expect the unexpected when it comes to machines. Last time we learned that under patent law the machine referred to in federal statute 35 USC § 101 includes any physical device consisting of two or more parts which dynamically interact with each other. We looked at how a purely mechanical machine, such as a diesel engine, has moving parts that are mechanically linked to dynamically interact when the engine runs. Now, lets move on to less obvious examples of what constitutes a machine. Would you expect a modern electronic memory stick to be a machine? Probably not. But, under patent law it is. It’s an electronic device, and as such it’s made up of multiple parts, including integrated circuit chips, resistors, diodes, and capacitors, all of which are soldered to a printed circuit board where they interact with one another. They do so electrically, through changing current flow, rather than through physical movement of parts as in our diesel engine. A transformer is an example of another type of machine. An electrical machine. Its fixed parts, including wire coils and steel cores, interact dynamically both electrically and magnetically in order to change voltage and current flow. Electromechanical, the most complex of all machine types, includes the kitchen appliances in your home. They consist of both fixed and moving parts, along with all the dynamic interactions of mechanical, electronic, and electrical machines. Next time we’ll continue our discussion on the second hurtle presented by 35 USC § 101, where we’ll discuss what is meant by article of manufacture. ___________________________________________ |

Determining Patent Eligibility – Part 2, Utility

Sunday, April 14th, 2013|

When I was growing up in the 1960s the Chicago Tribune featured a comic strip by Bill Holman called Smokey Stover. Smokey was a fireman who had all sorts of ridiculous, nutty, and even bazaar inventions, like his two-wheeled fire truck called the “Foomobile.” In the real world his inventions could never work, but that didn’t stop me from being a kid and enjoying Smokey’s goofy adventures. Smokey’s fire truck would never pass a patent test. Why? Because it wouldn’t get past the first requirement for patentability, that is, utility. Last time we introduced the federal laws governing patents as found in Title 35, Section 101, of the United States Code (USC), 35 USC § 101 for short. It sets out requirements for patentability, and the first hurdle that an invention must jump is that it must possess the quality of utility. In other words, it must be useful. This quality of utility prevents ridiculous and/or hypothetical devices, such as Smokey’s Foomobile, from receiving a patent. Because the Foomobile consists of an engine and two wheels mounted on a single axle, there’s nothing to keep it from falling over. The weight of its engine makes it front-heavy and unstable. The nutty vehicle will tip forward, and its front bumper will become wedged in the ground. The Foomobile is just not capable of passing the test of utility because it cannot be operated as intended – Smokey would never make it to the scene of the fire – and it’s unable to provide any identifiable benefit to its users. Once the hurdle of proving an invention’s utility is passed, the next considerations for patent eligibility must be addressed. Is the invention a machine? A process? Just what defines a machine? Is it something with gears and a motor? Next time we’ll see how within the context of patent eligibility, the word machine can apply to things which are not at all mechanical. ___________________________________________ |