Posts Tagged ‘energy’

Thursday, September 27th, 2018

|

Last time we introduced the phenomenon of uncontrollable factors as they exist within coal fired power plants. They inevitably result in lost energy in a number of ways, the most obvious of which is probably the smokestack, where lost energy is seen literally going up in smoke through the stack.

Energy Going up in Smoke Through the Stack

When coal is introduced into a coal fired power plant’s boiler, it’s combined with air, ignited, and begins to burn. This burning process releases some useful heat energy to fuel our power grids, but the rest goes up in smoke through the stack, releasing the products of the combustion process, including nitrogen, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and water vapor into the atmosphere.

Next time we’ll discuss friction, another factor which results in power plant energy loss.

Copyright 2018 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: boiler, combustion process, energy, power plant, stack

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, power plant training | Comments Off on Energy Going up in Smoke Through the Stack

Wednesday, December 6th, 2017

|

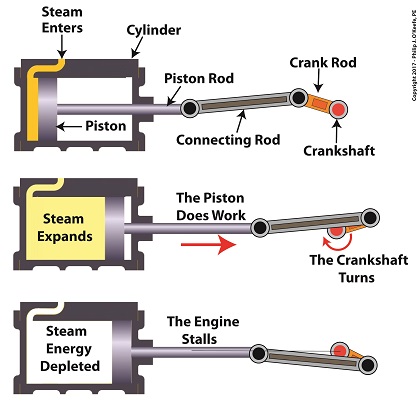

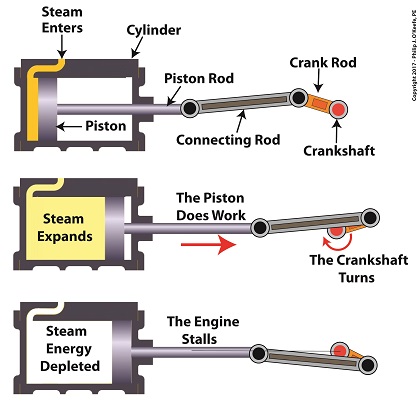

Last time we developed an engineering formula to calculate the horsepower required to accelerate a flywheel by way of a reciprocating steam engine, which contributes to the storage of kinetic energy inside a flywheel. Today we’ll gain a clearer understanding of how this works when we take a look inside a reciprocating steam engine.

A Look Inside a Reciprocating Steam Engine

A reciprocating steam engine performs the work of transforming steam’s heat energy into the mechanical energy needed to move a piston contained within a cylinder. During a complete operating cycle this piston travels from one end of the cylinder to the other, then back again. This is made possible because during the first half of the cycle pressurized steam enters one end of the cylinder and expands inside it, forcing the piston to move.

This process inside the cylinder results in movement of a piston that’s attached to a piston rod, which in turn is connected to a crankshaft via a connecting rod and crank rod. The crankshaft is a device which converts the reciprocating linear motion of an engine’s piston into rotary motion and in so doing facilitates the powering of any externally mounted rotating machinery attached to it. So long as there’s ample steam to power the internal piston, over time, energy in the form of horsepower will be available to externally mounted devices. The energy in the steam decreases as the steam expands behind the moving piston. So, the engine’s horsepower, will decrease as the piston travels to the end of the cylinder. If the energy in the steam should become depleted, the reciprocating steam engine will stall. The engine will no longer be able to perform work.

Next time we’ll see how a crankshaft works when we take a look inside it.

opyright 2017 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: connecting rod, crank rod, crankshaft, energy, engineering, flywheel, kinetic energy, piston rod, power, reciprocating steam engine, work

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on A Look Inside a Reciprocating Steam Engine

Monday, June 6th, 2016

|

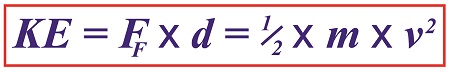

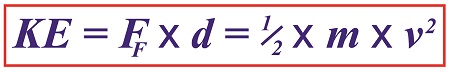

As an engineering expert, I often use the fact that formulas share a single common factor in order to set them equal to each other, which enables me to solve for a variable contained within one of them. Using this approach we’ll calculate the velocity, or speed, at which the broken bit of ceramic from the coffee mug we’ve been following slides across the floor until it’s finally brought to a stop by friction between it and the floor. We’ll do so by combining two equations which each solve for kinetic energy in their own way.

Last time we used this formula to calculate the kinetic energy, KE, contained within the piece,

KE = FF × d (1)

and we found that it stopped its movement across the floor when it had traveled a distance, d, of 2 meters.

We also solved for the frictional force, FF, which hampered its free travel, and found that quantity to be 0.35 kilogram-meters/second2. Thus the kinetic energy contained within that piece was calculated to be 0.70 kilogram-meters2/second2.

Now we’ll put a second equation into play. It, too, provides a way to solve for kinetic energy, but using different variables. It’s the version of the formula that contains the variable we seek to calculate, v, for velocity. If you’ll recall from a previous blog, that equation is,

KE = ½ × m × v2 (2)

Of the variables present in this formula, we know the mass, m, of the piece is equal to 0.09 kilograms. Knowing this quantity and the value derived for KE from formula (1), we’ll substitute known values into formula (2) and solve for v, the velocity, or traveling speed, of the piece at the beginning of its slide.

Combining Kinetic Energy Formulas to Calculate Velocity

The ceramic piece’s velocity is thus calculated to be,

KE = ½ × m × v2

0.70 kilogram-meters2/second2= ½ × (0.09 kilograms) × v2

now we’ll use algebra to rearrange things and isolate v to solve for it,

v2 = 2 × (0.70 kilogram-meters2/second2) ÷ (0.09 kilograms)

v = 3.94 meters/second =12.92 feet/second = 8.81 miles per hour

Our mug piece therefore began its slide across the floor at about the speed of an experienced jogger.

This ends our series on the interrelationship of energy and work. Next time we’ll begin a new topic, namely, how pulleys make the work of lifting objects and driving machines easier.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: distance, energy, engineering expert, friction, frictional force, kinetic energy, mass, velocity, work

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Combining Kinetic Energy Formulas to Calculate Velocity

Wednesday, May 25th, 2016

|

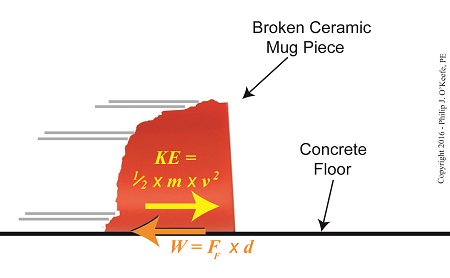

My activities as an engineering expert often involve creative problem solving of the sort we did in last week’s blog when we explored the interplay between work and kinetic energy. We used the Work-Energy Theorem to mathematically relate the kinetic energy in a piece of ceramic to the work performed by the friction that’s produced when it skids across a concrete floor. A new formula was derived which enables us to calculate the kinetic energy contained within the piece at the start of its slide by means of the work of friction. We’ll crunch numbers today to determine that quantity.

The formula we derived last time and that we’ll be working with today is,

Calculating Kinetic Energy By Means of the Work of Friction

where, KE is the ceramic piece’s kinetic energy, FF is the frictional force opposing its movement across the floor, and d is the distance it travels before friction between it and the less than glass-smooth floor brings it to a stop.

The numbers we’ll need to work the equation have been derived in previous blogs. We calculated the frictional force, FF, acting against a ceramic piece weighing 0.09 kilograms to be 0.35 kilogram-meters/second2 and the measured distance, d, it travels across the floor to be equal to 2 meters. Plugging in these values, we derive the following working equation,

KE = 0.35 kilogram-meters/second2 × 2 meters

KE = 0.70 kilogram-meters2/second2

The kinetic energy contained within that broken bit of ceramic is just about what it takes to light a 1 watt flashlight bulb for almost one second!

Now that we’ve determined this quantity, other energy quantities can also be calculated, like the velocity of the ceramic piece when it began its slide. We’ll do that next time.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: distance, electrical energy, energy, engineering expert, frictional force, kinetic energy, mass, velocity, Watt, work, work of friction, work-energy theorem

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Calculating Kinetic Energy By Means of the Work of Friction

Thursday, May 12th, 2016

|

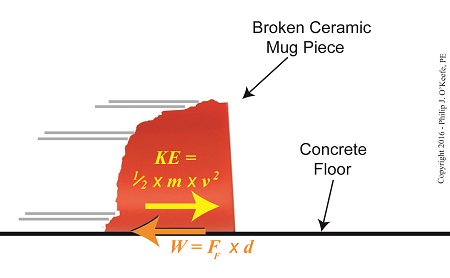

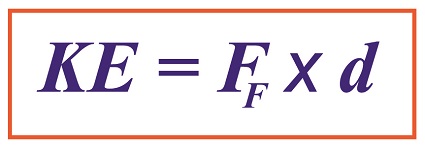

We’ve been discussing the different forms energy takes, delving deeply into de Coriolis’ claim that energy doesn’t ever die or disappear, it simply changes forms depending on the tasks it’s performing. Today we’ll combine mathematical formulas to derive an equation specific to our needs, an activity my work as an engineering expert frequently requires of me. Our task today is to find a means to calculate the amount of kinetic energy contained within a piece of ceramic skidding across a concrete floor. To do so we’ll combine the frictional force and Work-Energy Theorem formulas to observe the interplay between work and kinetic energy.

As we learned studying the math behind the Work-Energy Theorem, it takes work to slow a moving object. Work is present in our example due to the friction that’s created when the broken piece moves across the floor. The formula to calculate the amount of work being performed in this situation is written as,

W = FF ×d (1)

where, d is the distance the piece travels before it stops, and FF is the frictional force that stops it.

We established last time that our ceramic piece has a mass of 0.09 kilograms and the friction created between it and the floor was calculated to be 0.35 kilogram-meters/second2. We’ll use this information to calculate the amount of kinetic energy it contains. Here again is the kinetic energy formula, as presented previously,

KE = ½ × m × v2 (2)

where m represents the broken piece’s mass and v its velocity when it first begins to move across the floor.

The Interplay of Work and Kinetic Energy

The Work-Energy Theorem states that the work, W, required to stop the piece’s travel is equal to its kinetic energy, KE, while in motion. This relationship is expressed as,

KE = W (3)

Substituting terms from equation (1) into equation (3), we derive a formula that allows us to calculate the kinetic energy of our broken piece if we know the frictional force, FF, acting upon it which causes it to stop within a distance, d,

KE = FF × d

Next time we’ll use this newly derived formula, and the value we found for FF in our previous article, to crunch numbers and calculate the exact amount of kinetic energy contained with our ceramic piece.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: distance, energy, engineering expert, frictional force, kinetic energy, mass, velocity, work, work-energy theorem

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on The Interplay of Work and Kinetic Energy

Thursday, April 14th, 2016

|

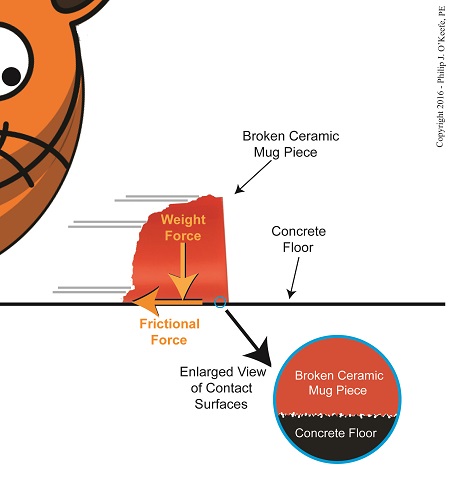

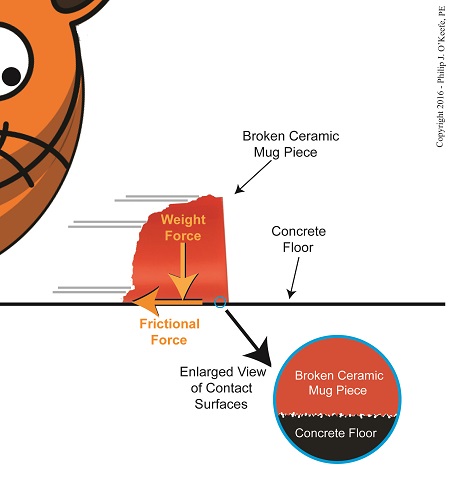

Last time we introduced the force of friction, another force in our ongoing discussion about changing forms of energy, and we learned that it’s often a counterproductive force which design engineers and engineering experts such as myself must work to minimize in order to optimize functionality of devices we’re designing. Today we’ll introduce the frictional force formula, which computes the amount of friction present when two surfaces meet.

To demonstrate frictional force, we’ve been working with the example of a shattered mug’s broken ceramic pieces and watching their progress as they slide across a concrete floor. They eventually come to a stop not too far from the point where the mug shattered, because friction causes them to stop. The mass of the ceramic pieces in combination with the downward pull of gravity causes the broken bits to “bear down” on the floor, thereby maximizing contact and creating friction.

At first glance the floor and mugs’ surfaces may appear slippery smooth, but when viewed under magnification we see that both actually contain many peaks and valleys. The peaks of one surface project into the valleys of the other and it’s fight, fight, fight for the ceramic pieces to continue their progress across the floor. The strength of the frictional force acting upon the pieces is a factor of their individual weights coupled with the roughness of the two surfaces coming into contact — the shattered pieces and the floor. If friction didn’t exist and no other impediments were in the way, the pieces might travel to the next state before stopping!

Frictional Force Resists Motion

Last time we introduced Charles-Augustin de Coulomb, a scientist whose work with friction led to the later development of a formula to calculate it. It’s presented here, and frictional force is denoted as FF,

FF = μ × m × g

where, m is the mass of an object making contact with another surface and g is the gravitational acceleration constant, which is due to the force of Earth’s gravity. The Greek letter μ, pronounced “mew,” represents the coefficient of friction, a number. Numerical values for μ were determined by laboratory testing and are recorded in engineering books for many combinations of materials, including rubber on concrete, leather on steel, wood on aluminum, and our own example of ceramic on concrete.

Next time we’ll plug the numbers that apply to our ceramic-on-concrete example into the friction formula and calculate the frictional force at play.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: Charles-Augustin de Coulomb, coefficient of friction, Earth's gravity, energy, engineering expert, friction, friction force formula, frictional force, gravitational acceleration constant, mass, mu

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on The Frictional Force Formula

Tuesday, March 15th, 2016

|

Last time we watched as the kinetic energy of our falling coffee mug was transformed into the work of creating a crater in a pan of soft kitty litter. Shock absorbing materials are often placed strategically to cushion valuable objects should they fall, and as an engineering expert I’ve sometimes had to implement break-its-fall solutions. Today we’ll place our mug into a less kind scenario, one in which it makes impact with the unforgiving hardness of a concrete floor. In so doing we’ll compare the mug’s ceramic to the floor’s concrete, and we’ll familiarize ourselves with the Mohs Scale of Hardness.

The Mohs Scale of Hardness, Ceramic vs. Concrete

Material hardness is commonly measured by the Mohs Scale of Hardness, which ranks the relative hardness of a material by observing how resistant it is to scratching by other materials harder than itself. This standard was developed by German mineralogist Friedrich Moh in 1812, and it rates objects’ hardness on a scale from 1.0, very soft, to 10.0, very hard. A fingernail, for example, ranks 2.5 on the scale, while a diamond ranks 10.0.

Now let’s take a look at the materials in our scenario, a ceramic mug and concrete floor, and see how they compare. The mug’s ceramic was created by mixing together clay, water, and other materials and then heating them in a kiln, a process known as firing. This firing causes a chemical reaction that bonds the individual materials tightly together, and when it cools it becomes the product we know as ceramic, a hard, brittle solid which registers at about 7.5 on the Mohs Scale.

The floor the mug falls to is poured-in-place cement, a compound consisting of primarily limestone, clay, pebbles and sand. When these materials are combined with water a chemical bonding takes place and forms the hard, stone-like matter we know as concrete, which comes in at about 8.0 on the Mohs Scale.

Although the mug’s ceramic is comparably hard to the floor’s concrete, its inherent brittleness, along with certain design features, most notably its handle, causes it to be fragile. Anyone broken a coffee mug lately?

As for the concrete floor the mug falls onto, it won’t yield to the mug’s freefall kinetic energy and form a crater like the litter did. So where does the mug’s energy go?

According to the Work-Energy Theorem, most of the mug’s kinetic energy is still converted into work, just as it was when it met up with the litter, but because the concrete floor is harder and thicker than the mug’s thin ceramic, the mug’s kinetic energy at impact falls back on itself rather than transferring externally into the concrete. The result is a shattered mug and a mess to clean up.

But we haven’t yet accounted for all the mug’s energy. We’ll find out what happens to the rest of it next time.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: brittleness, cement, ceramic, concrete, energy, engineering expert, force, freefall kinetic energy, hardness, Mohs Scale of Hardness, shatters, work, work-energy theorem

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Mohs Scale of Hardness, Ceramic vs. Concrete

Monday, February 8th, 2016

|

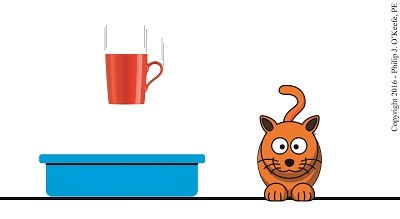

So far we’ve applied the Work-Energy Theorem to a flying object, namely, Santa’s sleigh, and a rolling object, namely, a car braking to avoid hitting a deer. Today we’ll apply the Theorem to a falling object, that coffee mug we’ve been following through this blog series. We’ll use the Theorem to find the force generated on the mug when it falls into a pan of kitty litter. This falling object scenario is one I frequently encounter as an engineering expert, and it’s something I’ve got to consider when designing objects that must withstand impact forces if they are dropped.

Applying the Work-Energy Theorem to Falling Objects

Here’s the Work-Energy Theorem formula again,

F × d = ½ × m × [v22 – v12]

where F is the force applied to a moving object of mass m to get it to change from a velocity of v1 to v2 over a distance, d.

As we follow our falling mug from its shelf, its mass, m, eventually comes into contact with an opposing force, F, which will alter its velocity when it hits the floor, or in this case a strategically placed pan of kitty litter. Upon hitting the litter, the force of the mug’s falling velocity, or speed, causes the mug to burrow into the litter to a depth of d. The mug’s speed the instant before it hits the ground is v1, and its final velocity when it comes to a full stop inside the litter is v2, or zero.

Inserting these values into the Theorem, we get,

F × d = ½ × m × [0 – v12]

F × d = – ½ × m × v12

The right side of the equation represents the kinetic energy that the mug acquired while in freefall. This energy will be transformed into Gaspard Gustave de Coriolis’ definition of work, which produces a depression in the litter due to the force of the plummeting mug. Work is represented on the left side of the equal sign.

Now a problem arises with using the equation if we’re unable to measure the mug’s initial velocity, v1. But there’s a way around that, which we’ll discover next time when we put the Law of Conservation of Energy to work for us to do just that.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: energy, engineering expert, falling objects, Gaspard-Gustave de Coriolis, impact forces, kinetic energy, law of conservation of energy, work, work-energy theorem

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury | Comments Off on Applying the Work-Energy Theorem to Falling Objects

Wednesday, January 20th, 2016

|

In my work as an engineering expert I’ve never had to convert Joules of work-energy into calories, but that’s exactly what we’ll be doing together today. Last time we applied the Work-Energy Theorem to the progress of Santa’s sleigh and found that an opposing wind force of 3848.7 Newtons –or 865.2 pounds for those of us who are American– slowed his team from an initial velocity of 90 meters per second to a final velocity of 40 meters per second and that it happened over a distance of 760 meters. Today we’ll see how many calories the reindeer need to expend to get them back up to full delivery speed.

Prancer Loves Oats

Now we know that Santa successfully made all his deliveries on time this past Christmas, so that means that at some point his reindeer team was able to get back up to full sleigh-flying speed. They did it by expending extra energy. We’ll use the Work-Energy Theorem to find out how much energy that equates to. Here’s the Theorem again,

W = ½ × m × [v22 – v12]

where W is the work/energy required to speed up the sleigh team’s mass, m, from an initial velocity v1 to a final velocity v2. For a refresher on the special relationship between work and energy, see our past blog on the subject.

If Santa’s sleigh has a mass of 900 kilograms and its speed must increase from 40 to 90 meters per second, then the work required to do so is calculated as,

W = ½ × (900 kilograms) × [(90 meters/second)2 – (40 meters/second)2]

W = ½ × (900 kilograms) × (6,500 meters2/second2)

W = 2,925,000 kilogram2 · meters2 per second2 = 2,925,000 Joules

So Rudolph and his buddies had to expend 2,925,000 Joules of energy to perform 2,925,000 Joules of work. To understand where Rudolph and his team got that energy, we must state things in terms of nutritional value, that is, units of calories.

Did you know that 1 calorie is equal to 4,184.43 Joules? Applying that equivalency to our situation we get,

Nutritional Energy Required = (2,925,000 Joules) × (4,184.43 Joules/calorie)

= 699.02 calories

The net result is Santa’s team expended a total of 699.02 calories for all the reindeer to regain their full speed of 90 meters per second. That’s the nutritional energy found in slightly more than one cup of oats. Now everybody knows that Santa takes good care of his reindeer, so undoubtedly they were fed plenty of oats and hay before takeoff. This was stored in their body fat for future, on-demand use.

Sadly, Christmas is over, and it’s time to get back to the more mundane aspects of life. Next time we’ll apply the principles behind the Work-Energy Theorem to calculate the braking force required to stop a car in motion.

Copyright 2015 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: calories, energy, engineering expert, Joules, mass, speed, velocity, work, work-energy theorem

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Work and Energy, Speed, and Calories

Friday, January 1st, 2016

|

As an engineering expert I’ve applied the Work-Energy Theorem to diverse situations, but none as unique as its most recent application, the progress of Santa’s sleigh. Last week we saw how Santa and his reindeer team encountered a wind gust which generated enough force to slow them from an initial velocity of v1 to a final velocity, v2, over a distance, d. Today we’ll begin using the Work-Energy Theorem to see if Santa was able to keep to his Christmas delivery schedule and get all the good boys and girls their gifts in time.

Before we can work with the Work-Energy Theorem, we must first revisit the formula it’s predicated upon, de Coriolis’ formula for kinetic energy,

KE = ½ × m × v2 (1)

where, KE is kinetic energy, m is the moving object’s mass, and v its velocity.

The equation behind the Work-Energy Theorem is,

W = KE2 – KE1 (2)

where W is the work performed, KE1 is the moving object’s initial kinetic energy and KE2 its final kinetic energy after it has slowed or stopped. In cases where the object has come to a complete stop KE2 is equal to zero, since the velocity of a stationary object is zero.

In order to work with equation (2) we must first expand it into a more useful format that quantifies an object’s mass and initial and final velocities. We’ll do that by substituting equation (1) into equation (2). The result of that term substitution is,

W = [½ × m × v22 ] – [½ × m × v12] (3)

Factoring out like terms, equation (3) is simplified to,

W = ½ × m × [v22 – v12] (4)

Now according to de Coriolis, work is equal to force, F, times distance, d. So substituting these terms for W in equation (4), the expanded version of the Work-Energy Theorem becomes,

F × d = ½ × m × [v22 – v12] (5)

Next time we’ll apply equation (5) to Santa’s delivery flight to calculate the strength of that gust of wind slowing him down.

Copyright 2015 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: de Coriolis, distance, energy, engineering expert, force, kinetic energy, mass, velocity, wind force, work, work-energy theorem

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury | Comments Off on The Math Behind the Work-Energy Theorem