|

What came first? The wheel or the flywheel? Archeologists have been debating this question for decades. One thing is certain, they both date back to prehistoric times. What Came First? The Wheel or the Flywheel?

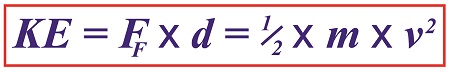

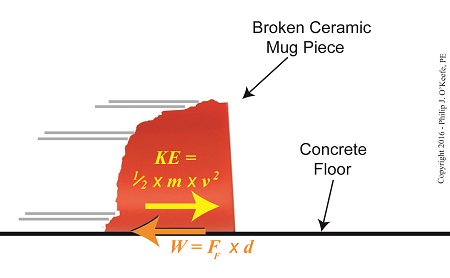

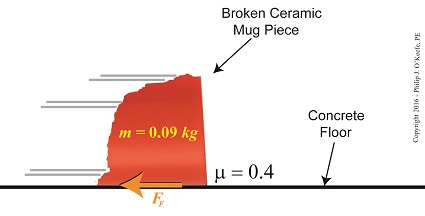

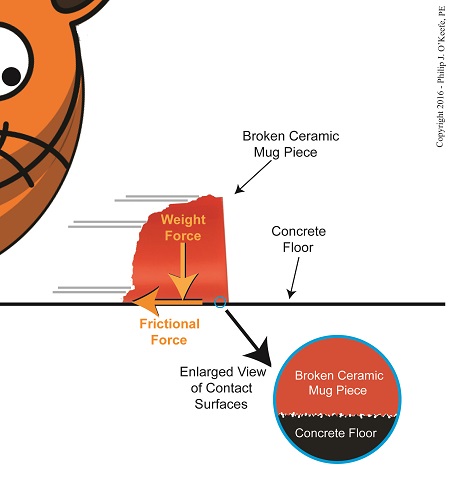

One of the oldest flywheel discoveries was a potter’s wheel, used to make pottery. It’s a turntable made of stone or heavy wood that’s connected to a massive wheel by a spinning shaft. Once the potter got the flywheel spinning with his hand or foot, the wheel’s heavy weight kept it in virtual perpetual motion, allowing the potter to concentrate on forming the clay he shaped with his hands. A potter’s wheel, or any other flywheel for that matter, takes a lot of initial effort to put into motion. In other words, the potter must put a lot of his own muscles’ mechanical energy into the flywheel to get it moving. That’s because its sheer weight binds it to the Law of Inertia and makes it want to stay at rest. But once the flywheel is in motion, the potter’s mechanical energy input is transformed into kinetic energy, the energy of motion. The kinetic energy the potter produces by his efforts results in surplus energy stored within the flywheel. Hence, the flywheel serves as a kinetic energy storage device, similar to a battery which stores electrical energy. As long as the flywheel remains in motion, this stored energy will be used to keep the turntable spinning, which results in no additional mechanical energy needing to be exerted by the potter while forming pots. The flywheel’s stored energy also makes it hard to stop once it’s in motion. But eventually the frictional force between the potter’s hands and the clay he works drains off all stored kinetic energy. Since the Industrial Revolution flywheels have been used to store kinetic energy to satisfy energy demands and provide a continuous output of power, which increases mechanical efficiency. Next time we’ll begin our exploration into the science behind flywheels and see how they’re used in diverse engineering applications.

Copyright 2017 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE Engineering Expert Witness Blog ____________________________________ |