| Ever discover a melted candy bar in your pocket? You immediately start to think about the sources for the heat that had caused the mess. Did you stand too close to the stove, were you outside in summer heat too long, or did you simply sit on it? Or was it perhaps caused by being in proximity to a whirring device, something which does not seem to generate any heat at all? If you’ve been reading along with us, you know what device I’m talking about.

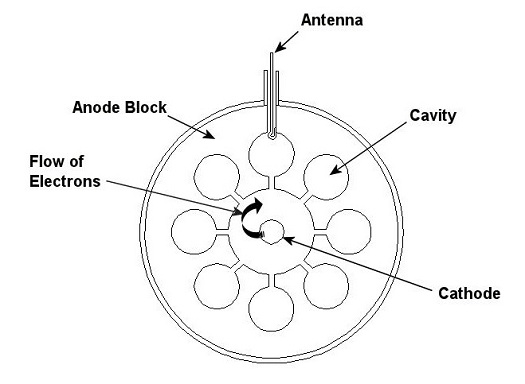

Last time we talked about an effect known as cavity resonance and how a sound is created, much like a musical note, when we blow across the top of a glass pop bottle containing some air space. Our breath causes the air molecules to bounce in and out of the bottle’s cavity, producing the sound. Microwave technology works in much the same way, making use of an electronic device called a resonant-cavity magnetron. But instead of generating a musical tone, like our breath does over the bottle, the magnetron produces short wavelength radio waves, known as microwaves, and it was initially developed to generate these microwaves for radar systems. So, how does the magnetron work? The magnetron contains a series of cavities arranged in a circle, their openings pointed towards the center as shown in Figure 1. Engineers determined that when a high voltage, say 4000 volts, is applied to the magnetron, it begins to boil off electrons through a filament, called a cathode, located at its center. Once free of the cathode, the electrons want to flow to a part of the magnetron called the anode. This is because the cathode is positively charged and the anode is negatively charged, and as we know, electrons like to flow from positive to negative. The anode is also the part of the magnetron containing the cavities, and we’ll see the significance of this in a moment. Figure 1 – Interior View of a Resonant-Cavity Magnetron Before the electrons can take their desired straight path to the anode, they are deflected by powerful magnets located on either end of the magnetron. These magnets force the electrons to move in a circular pattern over the openings in the cavities. Like the air molecules passing over the top of a pop bottle when you blow across it, the electrons move over each cavity opening in the magnetron, creating not musical tones, but microwaves. The microwaves are then collected from the magnetron using an antenna and directed along a tube called a wave guide. The microwaves leave the wave guide when they are transmitted by radar systems. The radar system then transmits the microwaves towards moving objects they wish to track. These tracked objects are as diverse as airplanes, ships, and weather patterns. See Figure 2. Figure 2 – Microwave Radar Transmission So, how does the microwave oven fit into our discussion? In 1946 an engineer by the name of Percy Spencer was working on a radar magnetron for the Raytheon Corporation, a producer of electronic technology for industry and defense. During the course of his work he unexpectedly exposed himself to microwaves from a wave guide, and he couldn’t help but notice that the candy bar in his pocket had melted. Putting two plus two together, he realized the microwaves had caused the candy bar to heat up. Dr. Spencer further experimented and came to the conclusion that microwaves can cook foods far more quickly than conventional ovens, and the modern day kitchen appliance was soon born. Next time we’ll look at how Dr. Spencer’s microwave cooking discovery was developed into the microwave oven we find in most kitchens. We’ll also see how even an unplugged microwave oven can pose an electrocution hazard, as I explained in the Discovery Channel program I was recently featured on, Curious and Unusual Deaths. _____________________________________________ |

Posts Tagged ‘resonance’

Microwave Radar and Melted Candy

Sunday, July 24th, 2011The Heart of the Microwave Oven

Monday, July 18th, 2011| In the world of inventions it happens with some regularity that an invention to do one thing unexpectedly leads to a device that does something completely different. Take for example Edison’s phonograph. At the time, he was working on an invention to record the dots and dashes of Morse code telegraph messages so they could be sent out repeatedly without an operator having to tap them out each time and possibly making mistakes while doing so. Little did he know that this would lead to the evolvement of the phonograph and recording industries.

Another invention “by mistake” took place when the resonant cavity magnetron, originally developed for use with microwave radar, led to the development of the microwave oven. Last week we talked about how long wave radar, the first type of radar to be developed, was effectively used by the British to repel enemy air attacks during World War II. But long wave radar was large and cumbersome to employ, and it soon evolved into an improved version, the shorter wave, or, as we know it, microwave radar. So what is this resonant cavity magnetron that led to its creation? A pop bottle can give us a clue. Blow across the top of an empty glass pop bottle (or soda bottle, depending on the part of the country you’re from) and a familiar resonant sound results. The sound is created by an effect known as cavity resonance, and other bona fide musical instruments make use of this phenomenon to produce musical sounds. How this works is that where a cavity exists, when air molecules are introduced into it, the molecules are caused to resonate in and out of the cavity many times per second. This creates a sound at a certain frequency, that frequency depending on the shape and dimensions of the cavity, as well as the size of its opening. The resonant cavity magnetron, or magnetron for short, is actually a high powered vacuum tube that operates in a very similar fashion to a pop bottle, or any other musical device making use of a cavity, but instead of using air molecules to generate sound waves, it uses electrons to generate short wavelength radio waves, called microwaves. The magnetron contains a series of cavities that are arranged in a circle with the openings pointing inward towards the center, as shown in Figure 1. Figure 1 – Interior View of a Resonant-Cavity Magnetron Next week we’ll see what this interesting looking device has in common with the simple act of blowing air across the top of a pop bottle and what this all has to do with microwaves. _____________________________________________ |