Posts Tagged ‘noise’

Monday, March 12th, 2018

|

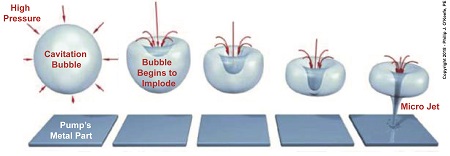

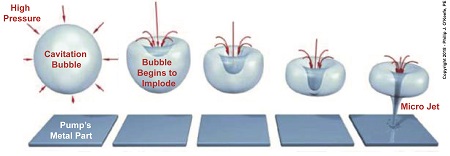

Last time we learned how both low and high pressures exist within a single centrifugal pump, and if water pressure at the inlet is low enough, the cavitation process begins. Today we’ll see how these rapidly imploding water vapor bubbles create serious problems in the pump’s high pressure area.

Rapidly Imploding Bubbles Create Problems

Water flows from low pressure at a centrifugal pump’s inlet to high pressure upstream when it meets up with the pump’s impeller. This high pressure causes cavitation bubbles formed at the inlet to rapidly implode, that is, collapse in on themselves. Implosion occurs because pressure outside the bubbles is much greater than the pressure inside them. This pressure difference exists because the bubbles were formed in the low pressure area of the pump.

When cavitation bubbles meet up with high pressure areas deep inside the pump, they get squeezed hard and burst rapidly, creating multitudes of shock waves, grinding noise, and vibration so intense it sounds as though gravel, not steam bubbles, are passing through the pump. The noise and vibration are bad enough, but cavitation has far worse consequences.

Rapidly imploding bubbles form tiny but powerful micro jets of water which hold an enormous amount of kinetic energy. When these jets hit the pump’s metal interior, their kinetic energy causes minute fragments of metal to break away. Over time these tiny water jets wear away enough metal to cause damage to the pump’s interior and interfere with function.

Next time we’ll see how cavitation bubbles flowing through the low pressure area of a pump degrade its performance.

opyright 2018 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: cavitation, cavitation bubbles imploding, centrifugal pump, micro jet, noise, pump high pressure area, pump low pressure area, shock waves, vibration

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, power plant training, Product Liability | Comments Off on Rapidly Imploding Bubbles Create Problems

Sunday, November 14th, 2010

|

How many crickets clicking their legs together in unison would it take before we would suffer hearing loss at the sound exposure? Would we need to sit in a garden filled with millions of them all night long, only to discover in the morning that we could no longer hear the tea kettle’s whistle? The chart below may not provide the answer to this question, but it does provide some very good examples of different sounds and the point at which they become hazardous.

So how do we know where we’re at safety-wise with sound pressure levels and exposure times? This question wasn’t pondered until the 1950s, when the military, specifically the Air Force, provided the first standards in this regard in 1956. This initial action was followed up by numerous studies and standards committees wrestling with the issue. It wasn’t until 1981 that the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) required employers to implement hearing conservation programs for employees in certain noise-filled environments.

What surprised many of the first scientists studying the impact of sound is that sounds don’t necessarily have to be initially perceived as “too loud” in order to cause hearing loss. Many sounds that we perceive as easily tolerated can in fact cause hearing damage if exposure is long enough.

So what’s “long enough?” Title 29 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Section 1910.95, lists the OSHA permissible sound exposure durations at various sound levels, as shown in Table 1.

|

| Duration of Exposure (Hrs.) |

Sound Level (dB) |

| 8 |

90 |

| 6 |

92 |

| 4 |

95 |

| 3 |

97 |

| 2 |

100 |

| 1.5 |

102 |

| 1 |

105 |

| 0.5 |

110 |

| 0.25 or less |

115 |

Table 1 – OSHA Permissible Noise Exposures

|

Just to put things into perspective, a small chain saw tearing into a log typically produces sound at 90dB, or 90 decibels, which you will recall from last week’s article is the measuring unit used for sound. And that noisy truck clattering down your street, the one that your dog can’t help but bark at, can produce 100dB. The guy standing on the airport tarmac directing your plane into the gate can be exposed to as much as 150dB. There’s a good reason he’s wearing ear protection.

Let’s take a closer look at the information provided in Table 1. It states that you most likely will not suffer hearing loss if you spend up to 8 hours in a place where the sound level does not exceed 90dB. Comparing that information to Table 2, which is specific to noises produced at a power plant, we see that this sound level is produced by the typical steam turbine.

One thing to keep in mind is that when we are exposed to various sounds throughout the day, we can compute a time-weighted average noise, or TWAN, to help us determine if our overall environment poses a threat to our hearing. This method of assessing the gross impact of many different sound exposures is represented by the formula:

TWAN = (C1 ÷ T1) + (C2 ÷ T2) + (C3 ÷ T3) + …

where C represents the total time of exposure at a measured sound level, and T represents the total time of exposure. T, which in our example stands for “hours,” is found in the left column of Table 1. Based on scientific studies of sound’s effects on the human ear, if the TWAN is greater than 1.0, then the exposure exceeds safe limits.

Let’s find out if a worker in a coal fired power plant is at risk of losing his hearing during the course of a typical eight hour workday. Table 2 shows the different noises he has to contend with during that time.

|

| Duration of Exposure (Hrs.) |

Location |

Sound Level (dB) |

| 0.5 |

Steam Turbine Basement |

90 |

| 2.5 |

Air Compressor Room |

95 |

| 0.25 |

Forced Draft Fan Gallery |

110 |

Table 2 – Example Exposure in an 8 Hour Day

|

Now let’s find out if his OSHA recommended sound exposure limit has been exceeded. The values for C, or total time of exposure, are given in the left column, and the corresponding sound level in dB’s is shown in the right column of Table 2. Using these numbers as a reference, we now correlate them with the information contained in Table 1 which cites the OSHA standards. Plugging in the numbers, we find that this worker’s TWAN would be:

TWAN = (0.5 hours ÷ 8 hours) + (2.5 hours ÷ 4 hours) + (0.25 hours ÷ 0.5 hours)

= 1.18

Since 1.18 is greater than 1.0, we see that the worker’s noise limit would indeed be exceeded. He would need to either wear hearing protection or limit his exposure time in order to comply with OSHA regulations and protect his hearing.

Next time we’ll discuss options open to us to control sounds in our environment.

_____________________________________________

|

Tags: air compressor, chain saw, dB, decibels, engineering expert witness, FD fan, forensic engineering, hearing damage, hearing loss, hearing protection, jet engine, loudness, noise, noise control, OSHA, power plant, sound, sound exposure, sound exposure standards, sound level measurement, steam turbine, time weighted average noise, TWAN

Posted in Engineering and Science, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Sound and Exposure Standards