| My first car was a used 1963 Dodge 880. It was reliable for the most part, but one day when I stepped on the brake in a supermarket parking lot, nothing happened. I began to roll down an incline, and I struggled to steer around the maze of parked cars in the lot. After what seemed to be an eternity I managed to navigate my way out of the lot into an adjacent cornfield. The soft ground and corn stalks finally brought me to a stop. I later discovered that the reason my brakes failed is because their linings had completely worn away.

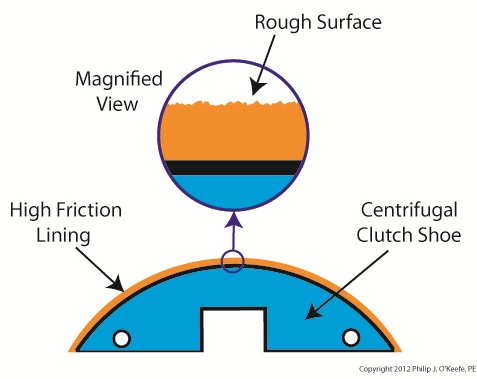

Like the brakes in cars, centrifugal clutch shoes also have linings as shown in Figure 1. Brake linings are typically made of a rough, high friction materials, such as ceramic compounds. These materials are bonded to the brake shoes, or in the case of clutches, to the clutch shoes. When centrifugal force comes into play, pressing the clutch shoes against the inside wall of the clutch housing, the roughness of the linings provides a good grip, preventing slippage between the shoes and the housing. Figure 1

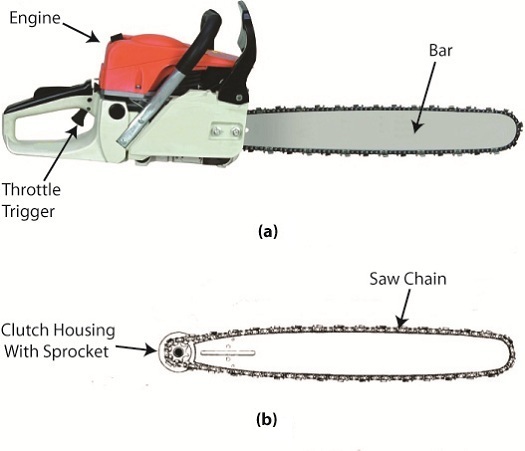

As we learned in previous articles, slip between the clutch shoes and clutch housings can create problems. In our grass trimmer for example, we learned that slippage reduces the amount of power the engine can effectively transmit to the cutter head. It also tends to produce a lot of heat. This heat can adversely effect the clutch springs and cause clutch failure. Although the high friction lining of the clutch shoes prevents most slippage, it can still occur, as when the throttle is depressed and engine speed increases beyond idle. There is some slipping as the clutch shoes first engage with the clutch housing, and it will continue until the engine speed increases to the point where centrifugal force causes the clutch shoes to firmly press into the clutch housing. Slippage also occurs when gasoline powered tools are subjected to operating stress. Figure 2 shows two views of a chainsaw. The first view is complete, the second shows the chain and clutch housing in isolation. Figure 2

With the engine housing removed, we see that the saw chain is connected to a sprocket located on the centrifugal clutch housing. This sprocket is similar to those that engage the chains on bicycle wheels. Now suppose someone decides to use the chainsaw to cut a green, sap-filled log. To make matters worse, let’s suppose the chainsaw has a dull saw chain. If you’ve ever tried doing this, you know that the sticky, sappy wood will eventually gum up the chain and stop it from moving. Since the chain is connected to the clutch housing, it stops as well. However the clutch shoes, which are driven by the engine, keep trying to move the gummed-up clutch housing, because the engine’s power is enough to overcome some of the friction. The result is that the shoes slip uselessly inside the housing. Over time, continued slippage will cause the clutch shoes’ high friction lining to wear away. Once the lining is gone the clutch shoes will slip excessively, even when the gasoline powered tool is being employed to perform the lightest task. That’s because slipping prevents a good portion of the engine’s power from being transmitted to the cutting head. That’s it for our series on centrifugal clutches. Next we’ll be discussing transistors, how they’re used in electronic controls to switch things on and off and perform other functions. ____________________________________________ |

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

Published by Philip J. O'Keefe, PE, MLE