Archive for the ‘Expert Witness’ Category

Saturday, January 28th, 2017

|

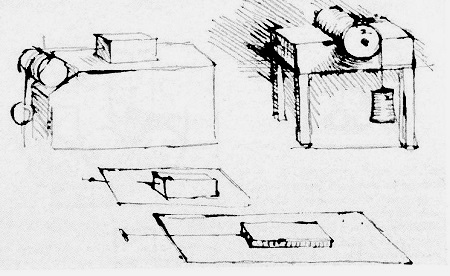

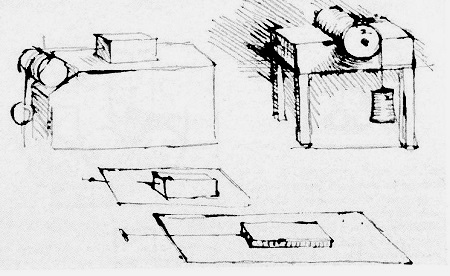

In our blog series on pulleys we’ve been discussing the effects of friction, subjects also studied by Leonardo da Vinci, a historical figure whose genius contributed so much to the worlds of art, engineering, and science. The tribometre shown in his sketch here is one of history’s earliest recorded attempts to understand the phenomenon of friction. Tribology, according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, is “a study that deals with the design, friction, wear, and lubrication of interacting surfaces in relative motion.” Depicted in da Vinci’s sketch are what appear to be pulleys from which dangle objects in mid-air.

da Vinci’s Tribometre; a Historical Look at Pulleys and Friction

Copyright 2017 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: engineering, friction, Leonardo Da Vinci, pulleys, tribometre

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury | Comments Off on da Vinci’s Tribometre; a Historical Look at Pulleys and Friction

Monday, January 16th, 2017

|

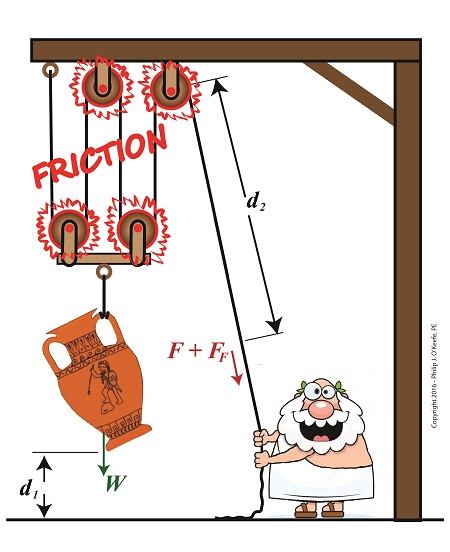

We left off last time with an engineering analysis of energy factors within a compound pulley scenario, in our case a Grecian man lifting an urn. We devised an equation to quantify the amount of work effort he exerts in the process. That equation contains two terms, one of which is beneficial to our lifting scenario, the other of which is not. Today we’ll explore these two terms and in so doing show how there are situations when work input does not equal work output.

Work Input Does Not Equal Work Output

Here again is the equation we’ll be working with today,

WI = (F × d) + (FF × d) (1)

where, F is the entirely positive force, or work, exerted by human or machine to lift an object using a compound pulley. It represents an ideal but not real world scenario in which no friction is present within the pulley assembly.

The other force at play in our lifting scenario, FF, is less obvious to the casual observer. It’s the force, or work, which must be employed over and above the initial positive force to overcome the friction that’s always present between moving parts, in this case a rope moving through pulley wheels. The rope length extracted from the pulley to lift the object is d.

Now we’ll use this equation to understand why work input, WI, does not equal work output, WO, in a compound pulley arrangement where friction is present.

The first term in equation (1), (F × d), represents the work input as supplied by human or machine to lift the object. It is an idealistic scenario in which 100% of energy employed is directly conveyed to lifting. Stated another way, (F × d) is entirely converted into beneficial work effort, WO.

The second term, (FF × d), is the additional work input that’s needed to overcome frictional resistance present in the interaction between rope and pulley wheels. It represents lost work effort and makes no contribution to lifting the urn off the ground against the pull of gravity. It represents the heat energy that’s created by the movement of rope through the pulley wheels, heat which is entirely lost to the environment and contributes nothing to work output. Mathematically, this relationship between WO, WI, and friction is represented by,

WO = WI – (FF × d) (2)

In other words, work input is not equal to work output in a real world situation in which pulley wheels present a source of friction.

Next time we’ll run some numbers to demonstrate the inequality between WI and WO.

Copyright 2017 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: compound pulley, engineering, friction, heat energy, pulley, work input, work output

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Work Input Does Not Equal Work Output

Saturday, January 7th, 2017

|

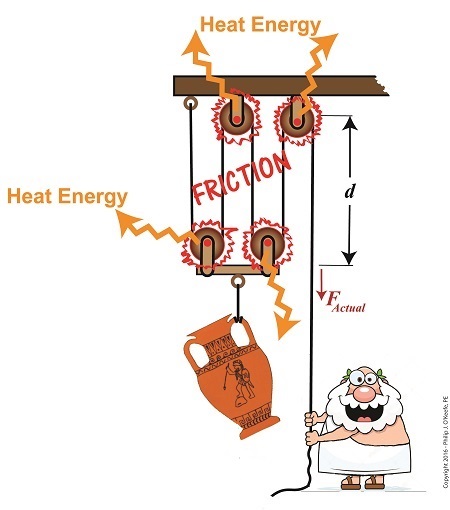

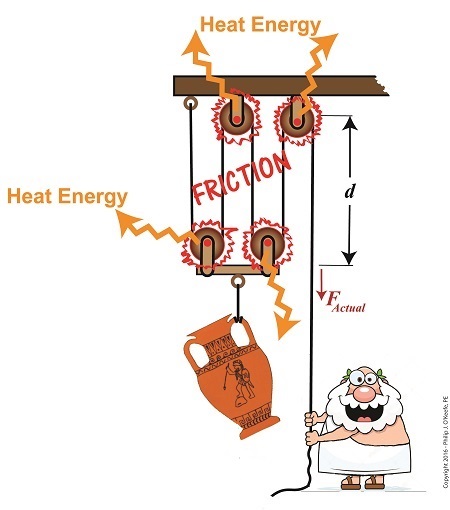

Last time we saw how the presence of friction reduces mechanical advantage in an engineering scenario utilizing a compound pulley. We also learned that the actual amount of effort, or force, required to lift an object is a combination of the portion of the force which is hampered by friction and an idealized scenario which is friction-free. Today we’ll begin our exploration into how friction results in reduced work input, manifested as heat energy lost to the environment. The net result is that work input does not equal work output and some of Mr. Toga’s labor is unproductive.

Friction Results in Heat and Lost Work Within a Compound Pulley

In a past blog, we showed how the actual force required to lift our urn is a combination of F, an ideal friction-free work effort by Mr. Toga, and FF , the extra force he must exert to overcome friction present in the wheels,

FActual = F + FF (1)

Mr. Toga is clearly working to lift his turn, and generally speaking his work effort, WI, is defined as the force he employs multiplied by the length, d, of rope that he pulls out of the compound pulley during lifting. Mathematically that is,

WI = FActual × d (2)

To see what happens when friction enters the picture, we’ll first substitute equation (1) into equation (2) to get WI in terms of F and FF,

WI = (F + FF ) × d (3)

Multiplying through by d, equation (3) becomes,

WI = (F × d )+ (FF × d) (4)

In equation (4) WI is divided into two terms. Next time we’ll see how one of these terms is beneficial to our lifting scenario, while the other is not.

Copyright 2017 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: compound pulley, engineering, friction, heat energy, lost work, mechanical advantage, pulley, reduced work, work input, work output

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability, Professional Malpractice | Comments Off on Friction Results in Heat and Lost Work Within a Compound Pulley

Monday, December 19th, 2016

Tags: engineering expert, engineering expert witness, pulleys

Posted in Courtroom Visual Aids, Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, power plant training, Product Liability, Professional Malpractice | Comments Off on Pulleys Make Santa’s Job Easier

Tuesday, December 13th, 2016

|

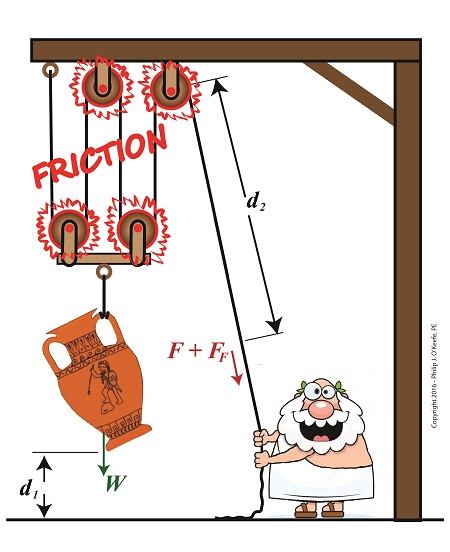

The presence of friction in mechanical designs is as guaranteed as conflict in a good movie, and engineers inevitably must deal with the conflicts friction produces within their mechanical designs. But unlike a good movie, where conflict presents a positive, engaging force, friction’s presence in pulleys results only in impediment, wasting energy and reducing mechanical advantage. We’ll investigate the math behind this phenomenon in today’s blog.

Friction Reduces Pulleys’ Mechanical Advantage

A few blogs back we performed a work input-output analysis of an idealized situation in which no friction is present in a compound pulley. The analysis yielded this equation for mechanical advantage,

MA = d2 ÷ d1 (1)

where d2 is the is the length of rope Mr. Toga extracts from the pulley in order to lift his urn a distance d1 above the ground. Engineers refer to this idealized frictionless scenario as an ideal mechanical advantage, IMA, so equation (1) becomes,

IMA = d2 ÷ d1 (2)

We also learned that in the idealized situation mechanical advantage is the ratio of the urn’s weight force, W, to the force exerted by Mr. Toga, F, as shown in the following equation. See our past blog for a refresher on how this ratio is developed.

IMA = W ÷ F (3)

In reality, friction exists between a pulley’s moving parts, namely, its wheels and the rope threaded through them. In fact, the more pulleys we add, the more friction increases.

The actual amount of lifting force required to lift an object is a combination of FF , the friction-filled force, and F, the idealized friction-free force. The result is FActual as shown here,

FActual = F + FF (4)

The real world scenario in which friction is present is known within the engineering profession as actual mechanical advantage, AMA, which is equal to,

AMA = W ÷ FActual (5)

To see how AMA is affected by friction force FF, let’s substitute equation (4) into equation (5),

AMA = W ÷ (F + FF) (6)

With the presence of FF in equation (6), W gets divided by the sum of F and FF . This results in a smaller number than IMA, which was computed in equation (3). In other words, friction reduces the actual mechanical advantage of the compound pulley.

Next time we’ll see how the presence of FF translates into lost work effort in the compound pulley, thus creating an inequality between the work input, WI and work output WO.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: actual mechanical advantage, AMA, compound pulley, engineering, friction, friction force, ideal mechanical advantage, IMA, mechanical advantage, mechanical design, pulley, pulley friction, pulley work input, pulley work output, weight force

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Friction Reduces Pulleys’ Mechanical Advantage

Wednesday, November 30th, 2016

|

We’ve been discussing the mechanical advantage that compound pulleys provide to humans during lifting operations and last time we hit upon the fact that there comes a point of diminished return, a reality that engineers must negotiate in their mechanical designs. Today we’ll discuss one of the undesirable tradeoffs that results in a diminished return within a compound pulley arrangement when we compute the length of rope the Grecian man we’ve been following must grapple in order to lift his urn. What we’ll discover is a situation of mechanical overkill – like using a steamroller to squash a bug.

Mechanical Overkill

Just how much rope does Mr. Toga need to extract from our working example compound pulley to lift his urn two feet above the ground? To find out we’ll need to revisit the fact that the compound pulley is a work input-output device.

As presented in a past blog, the equations for work input, WI, and work output, WO, we’ll be using are,

WI = F × d2

WO = W × d1

Now, ideally, in a compound pulley no friction exists in the wheels to impede the rope’s movement, and that will be our scenario today. Our next blog will deal with the more complex situation where friction is present. So for our example today, with no friction present, work input equals output…

WI = WO

… and this fact allows us to develop an equation in terms of the rope length/distance factors in our compound pulley assembly, represented by d1 and d2, …

F × d2 = W × d1

d2 ÷ d1 = W ÷ F

Now, from our last blog we know that W divided by F represents the mechanical advantage, MA, to Mr. Toga of using the compound pulley, which was found to be 16, equivalent to the sections of rope directly supporting the urn. We’ll set the distance factors up in relation to MA, and the equation becomes…

d2 ÷ d1 = MA

d2 = MA × d1

d2 = 16 × 2 feet = 32 feet

What we discover is that in order to raise the urn 2 feet, our Grecian friend must manipulate 32 feet of rope – which would only make sense if he were lifting something far heavier than a 40 pound urn.

In reality, WI does not equal WO, due to the inevitable presence of friction. Next time we’ll see how friction affects the mechanical advantage in our compound pulley.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: compound pulley, engineer, force times distance, lift, mechanical advantage, mechanical design, pulley, rope length, work, work input, work output

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Mechanical Overkill, an Undesirable Tradeoff in Compound Pulleys

Sunday, November 6th, 2016

|

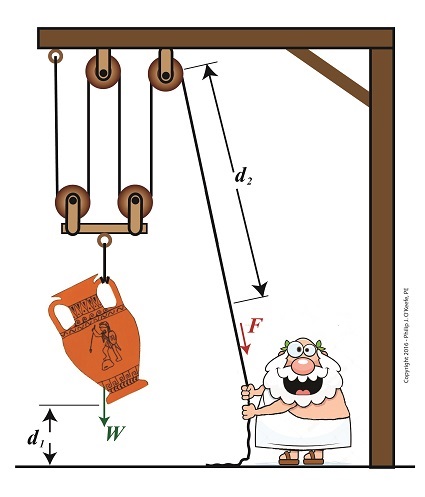

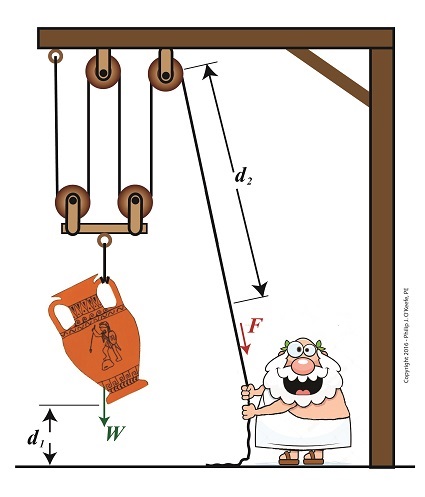

In our last blog we saw how adding extra pulleys resulted in mechanical advantage being doubled, which translates to a 50% decreased lifting effort over a previous scenario. Pulleys are engineering marvels that make our lives easier. Theoretically, the more pulleys you add to a compound pulley arrangement, the greater the mechanical advantage — up to a point. Eventually you’d encounter undesirable tradeoffs. We’ll examine those tradeoffs, but before we do we’ll need to revisit the engineering principle of work and see how it applies to compound pulleys as a work input-output device.

Pulleys as a Work Input-Outut Device

The compound pulley arrangement shown includes distance notations, d1 and d2. Their inclusion allows us to see it as a work input-output device. Work is input by Mr. Toga, we’ll call that WI, when he pulls his end of the rope using his bicep force, F. In response to his efforts, work is output by the compound pulley when the urn’s weight, W, is lifted off the ground against the pull of gravity. We’ll call that work output WO.

In a previous blog we defined work as a factor of force multiplied by distance. Using that notation, when Mr. Toga exerts a force F to pull the rope a distance d2 , his work input is expressed as,

WI = F × d2

When the compound pulley lifts the urn a distance d1 above the ground against gravity, its work output is expressed as,

WO = W × d1

Next time we’ll compare our pulley’s work input to output to develop a relationship between d1 and d2. This relationship will illustrate the first undesirable tradeoff of adding too many pulleys.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: compound pulley, distance, engineering, engineering principle, force, mechanical advantage, pulley, weight, work, work input-output device, work of lifting

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Pulleys as a Work Input-Outut Device

Friday, October 14th, 2016

|

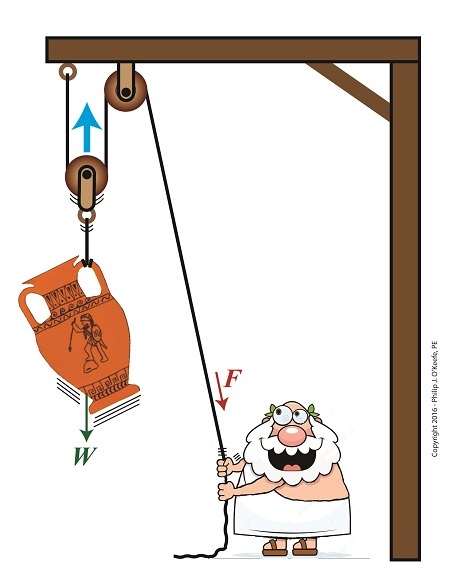

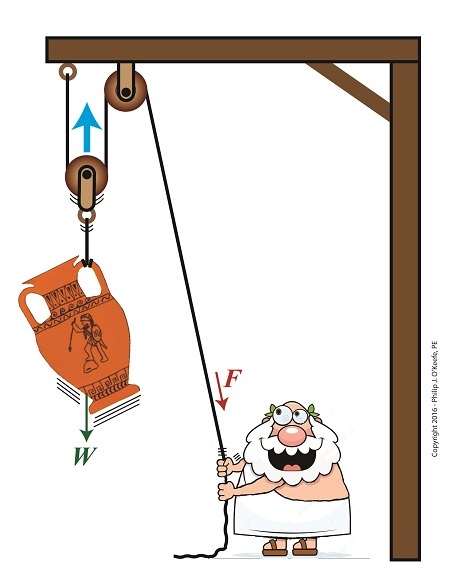

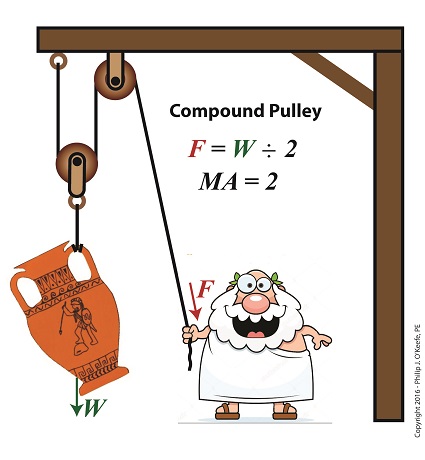

Last time we introduced the engineering concept of mechanical advantage, MA. Thanks to its presence in our compound pulley arrangement, it made a Grecian man’s job of holding an urn suspended in space twice as easy as compared to when he used a mere simple pulley. Today we’ll see what happens when our static scenario becomes active through dynamic lifting and how it affects his efforts.

Dynamic Lifting is Easier With a Compound Pulley

If you’ll recall from our last blog, Mr. Toga used a compound pulley to assist him in holding an urn stationary in space. To do so, he only needed to exert personal bicep force, F, equivalent to half the urn’s weight force, W, which meant he enjoyed a mechanical advantage of 2. Mathematically that is represented by,

F = W ÷ 2

If the urn weighs 40 pounds, then he only needs to exert 20 Lbs of personal effort to keep it suspended.

But when Mr. Toga uses more bicep power with that same compound pulley, he’s able to dynamically raise its position in space until it eventually meets with the beam that supports it. All the while he’ll be exerting a force greater than W ÷ 2. That relationship is represented by,

F > W ÷ 2

In the case of a 40 Lb urn, the lifting force Mr. Toga must exert to dynamically lift the urn is represented by,

F > 40 Lbs ÷ 2

F > 20 Lbs

where F represents a bicep force of at least 20 pounds. Fortunately for him, his efforts will never have to extend much beyond 20 Lbs of effort to lift the urn to the beam. That’s because gravity’s effect will remain nearly constant as the urn climbs, this being due to gravity’s influence upon objects decreasing by an insignificant amount over short distances above the Earth’s surface. As a matter of fact, at an altitude of 3,280 feet, gravity’s pull decreases by a mere 0.2 %.

The net result is that the compound pulley enables the same mechanical advantage whether a static or dynamic scenario exists, that is, regardless of whether Mr. Toga is simply holding the urn stationary in space or he’s actively tugging on his end of the rope to lift it higher.

Next time we’ll see how mechanical advantage increases when we add more fixed and moveable pulleys to our compound pulley arrangement.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: compound pulley, dynamic lifting, engineering expert, force, gravity, gravity's pull, mechanical advantage, simple pulley, static, weight

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Dynamic Lifting is Easier With a Compound Pulley

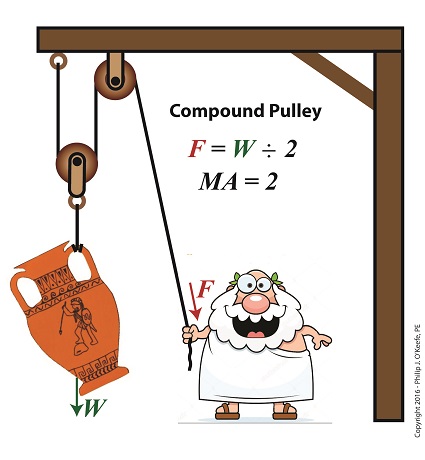

Thursday, September 29th, 2016

|

In this blog series on pulleys we’ve gone from discussing the simple pulley to the improved simple pulley to an introduction to the complex world of compound pulleys, where we began with a static representation. We’ve used the engineering tool of a free body diagram to help us understand things along the way, and today we’ll introduce another tool to prepare us for our later analysis of dynamic compound pulleys. The tool we’re introducing today is the engineering concept of mechanical advantage, MA, as it applies to a compound pulley scenario.

The term mechanical advantage is used to describe the measure of force amplification achieved when humans use tools such as crowbars, pliers and the like to make the work of prying, lifting, pulling, bending, and cutting things easier. Let’s see how it comes into play in our lifting scenario.

During our previous analysis of the simple pulley, we discovered that in order to keep the urn suspended, Mr. Toga had to employ personal effort, or force, equal to the entire weight of the urn.

F = W (1)

By comparison, our earlier discussion on the static compound pulley revealed that our Grecian friend need only exert an amount of personal force equal to 1/2 the suspended urn’s weight to keep it in its mid-air position. The use of a compound pulley had effectively improved his ability to suspend the urn by a factor of 2. Mathematically, this relationship is demonstrated by,

F = W ÷ 2 (2)

The factor of 2 in equation (2) represents the mechanical advantage Mr. Toga realizes by making use of a compound pulley. It’s the ratio of the urn’s weight force, W, to the employed force, F. This is represented mathematically as,

MA = W ÷ F (3)

Substituting equation (2) into equation (3) we arrive at the mechanical advantage he enjoys by making use of a compound pulley,

MA = W ÷ (W ÷ 2) = 2 (4)

Mechanical Advantage of a Compound Pulley

Next time we’ll apply what we’ve learned about mechanical advantage to a compound pulley used in a dynamic lifting scenario.

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: compound pulley, engineering, force, lifting, mechanical advantage, pulley, simple pulley, static analysis, tools, weight

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Mechanical Advantage of a Compound Pulley

Thursday, September 22nd, 2016

|

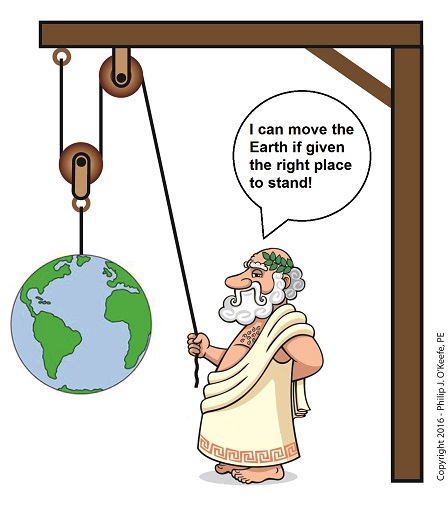

Archimedes, a Greek mathematician of ancient times, is credited with inventing the compound pulley, a subject we’ve been exploring recently. He was so confident in his invention, he’s said to have remarked, “I could move the Earth if given the right place to stand.”

Archimedes and the Compound Pulley

Copyright 2016 – Philip J. O’Keefe, PE

Engineering Expert Witness Blog

____________________________________ |

Tags: Archimedes, compound pulley

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability | Comments Off on Archimedes and the Compound Pulley