|

We’ve been working towards a general understanding of how gear trains work, and today we’ll solve a final piece of the puzzle when we identify how increased gear train torque is gained at the expense of gear train speed. Last time we developed a mathematical relationship between the torque, T, and the rotational speed, n, of the driving and driven gears in a simple gear train. This is represented by equation (8): TDriven ÷ TDriving = nDriving ÷ nDriven (8) For the purpose of our example we’ll assume that the driving gear is mounted to an electric motor shaft spinning at 100 revolutions per minute (RPM) and which produces 50 inch pounds of torque. Previous lab testing has determined that we require a torque of 100 inch pounds to properly run a piece of machinery that’s powered by the motor, and we’ve decided that the best way to get the required torque is not to employ a bigger, more powerful motor, but rather to install a gear train and manipulate its gear sizes until the desired torque is obtained. We know that using this approach will most likely affect the speed of our operation, and we want to determine how much speed will be compromised. So if the torque on the driven gear needs to be 100 inch pounds, then what will be the corresponding speed of the driven gear? To answer this question we’ll insert the numerical information we’ve been provided into equation (8). Doing so we arrive at the following: TDriven ÷ TDriving = nDriving ÷ nDriven (100 inch pounds) ÷ (50 inch pounds) = (100 RPM) ÷ nDriven 2 = (100 RPM) ÷ nDriven nDriven = (100 RPM) ÷ 2 = 50 RPM This tells us that in order to meet our torque requirement of 100 inch pounds, the gear train motor’s speed must be reduced from 100 RPM to 50 RPM, which represents a 50% reduction in speed, hence the tradeoff. This wraps up our blog series on gears and gear trains. Next time we’ll move on to a new topic: Galileo’s experiments with falling objects.

_______________________________________

|

Posts Tagged ‘machinery expert’

Determining the Gear Train Tradeoff of Torque vs. Speed, Part Three

Wednesday, August 27th, 2014The Methodology Behind Gear Train Torque Conversions

Sunday, June 22nd, 2014|

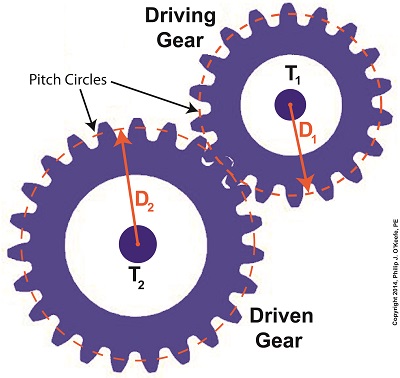

Last time we learned that gear trains are torque converters, and we developed a torque ratio equation which mathematically ties the two gears in a gear train together. That equation is: T1 ÷ T2 = D1 ÷ D2 Engineers typically use this equation knowing only the value for T2, the torque required to properly drive a piece of machinery. That knowledge is acquired through trial testing during the developmental phase of manufacturing. Once T2 is known, a stock motor is selected from a catalog with a torque value T1 which closely approximates that of the required torque, T2. Then calculations are performed and lab tests are run to determine the driving and driven gear sizes, D1 and D2 which will enable the gear train to convert T1 into the required value of T2. This series of operations are often a time consuming and complex process. To simplify things for the purpose of our example, we’ll say we’ve been provided with all values required for our equation, except one, the value of T2. In other words, we’ll be doing things in a somewhat reverse order, because our objective is simply to see how a gear train converts a known torque T1 into a higher torque T2. We’ll begin by considering the gear train illustration above. For our purposes it’s situated between an electric motor and the lathe it’s powering. The motor exerts a torque of 200 inch pounds upon the driving gear shaft of the lathe, a torque value that’s typical for a mid sized motor of about 5 horsepower. As-is, this motor is unable to properly drive the lathe, which is being used to cut steel bars. We know this because lab testing has shown that the lathe requires at least 275 inch pounds of torque in order to operate properly. Will the gears on our gear train be able to provide the required torque? We’ll find out next time when we insert values into our equation and run calculations. _______________________________________

|

Gear Train Torque Equations

Thursday, May 22nd, 2014|

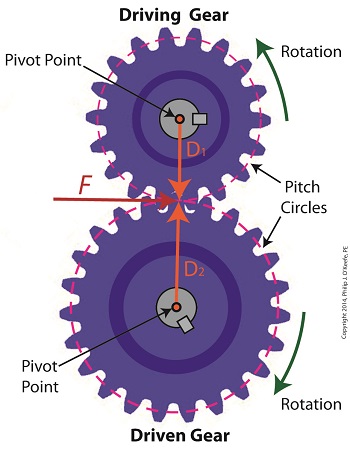

In our last blog we mathematically linked the driving and driven gear Force vectors to arrive at a single common vector F, known as the resultant Force vector. This simplification allows us to achieve common ground between F and the two Distance vectors of our driving and driven gears, represented as D1 and D2. We can then use this commonality to develop individual torque equations for both gears in the train. In this illustration we clearly see that the Force vector, F, is at a 90º angle to the two Distance vectors, D1 and D2. Let’s see why this angular relationship between them is crucial to the development of torque calculations. First a review of the basic torque formula, presented in a previous blog, Torque = Distance × Force × sin(ϴ) By inserting D1, F, and ϴ = 90º into this formula we arrive at the torque calculation, T1 , for the driving gear in our gear train: T1 = D1 × F × sin(90º) From a previous blog in this series we know that sin(90º) = 1, so it becomes, T1 = D1 × F By inserting D2, F, and ϴ = 90º into the torque formula, we arrive at the torque calculation, T2 , for the driven gear: T2 = D2 × F × sin(90º) T2 = D2 × F × 1 T2 = D2 × F Next week we’ll combine these two equations relative to F, the common link between them, and obtain a single equation equating the torques and pitch circle radii of the driving and driven gears in the gear train. _______________________________________ |

When Do You Need To Modify Gear Ratio?

Wednesday, February 19th, 2014|

Last time we saw how the involute profile of spur gear teeth ensures smooth contact between gears when they rotate. Today we’ll see why it’s important to be able to change the rotational speed of the driven gear in relation to that of the driving gear by modifying their gear ratio, the speeds at which gears move relative to one another. Why would we want to modify the rotational speeds of gears relative to one another? One reason is to compensate for the fact that alternating electric current (AC) motors drive most modern machinery, and these motors operate at a fixed speed determined by the 60 cycles per second frequency of electricity provided by the utility power grids of North America. By fixed speed I mean that the motor’s shaft revolves at a single, fixed rate. It can’t run any faster or slower. This is fine for some motorized applications, but not others. Basic machinery such as wood cutting saws, grinders, and blowers function well within the parameters of the AC motor’s fixed speed, because their working parts are intended to rotate at the same rate as the motor’s shaft. As a matter of fact, in this instance there’s often no need for a gear train, because the working parts can be connected directly to the motor’s shaft, and the machinery will be powered and function correctly. There are many instances however in which a fixed speed does not match the speed required for more complex machinery to correctly perform precise, specialized tasks. Take a machine tool meant to cut steel bars, for example. It has a rotating part meant to cut through the steel during machining, and to properly do so its cutting tool bit must turn at 400 revolutions per minute (RPM). If it turns any faster, the cut won’t be smooth and the tool bit will overheat and break due to increased friction. If the AC motor driving the machine tool turns at 1750 RPM, a common speed for such motors, then the tool bit will be turning at a much faster rate than the desired 400 RPM, and this presents a problem. To solve the problem we need only add a gear train between the motor and the part containing the tool bit, meaning, we must connect the gear train’s driving gear to the motor’s shaft and a driven gear to the part’s shaft. But in order for this arrangement to work a conversion must take place, that is, we must design the gear train to operate at a specific gear ratio. By gear ratio, I mean the speeds at which the two gears will rotate relative to one another. Next time we’ll introduce the gear ratio formulas that make it all work.

_______________________________________ |