| Ever been in the basement when you heard a loud thud followed by a scream by a family member upstairs? You run up the stairs to see what manner of calamity has happened, the climb seeming to take an eternity. Imagine a similar scenario taking place in an industrial setting, where distances to be covered are potentially far greater and the dangerous scenarios numerous.

Suppose an employee working near a conveyor system notices that a coworker’s gotten caught in the mechanism. The conveyor has to be shut down fast, but the button to stop the line is located far away in the central control room. This is when emergency stop buttons come to the rescue, like the colorful example shown in Figure 1. Figure 1

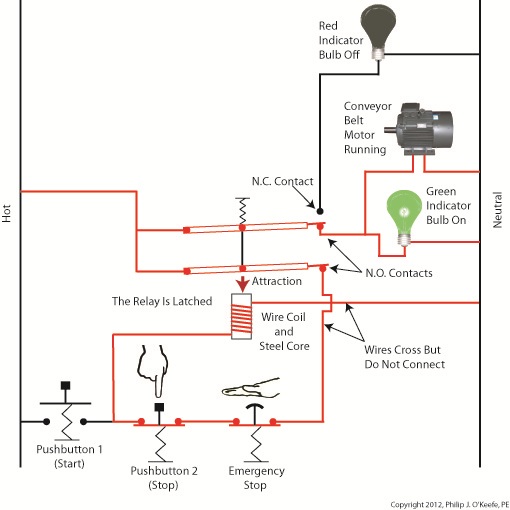

Emergency stop buttons are mounted near potentially dangerous equipment in industrial settings, allowing workers in the area to quickly de-energize equipment should a dangerous situation arise. These buttons are typically much larger than your standard operational button, and they tend to be very brightly colored, making them stick out like a sore thumb. This type of notoriety is desirable when a high stress situation requiring immediate attention takes place. They’re easy to spot, and their shape makes them easy to activate with the smack of a nearby hand, broom, or whatever else is convenient. Figure 2 shows how an emergency stop button can be incorporated into a typical motor control circuit such as the one we’ve been working with in previous articles. Figure 2

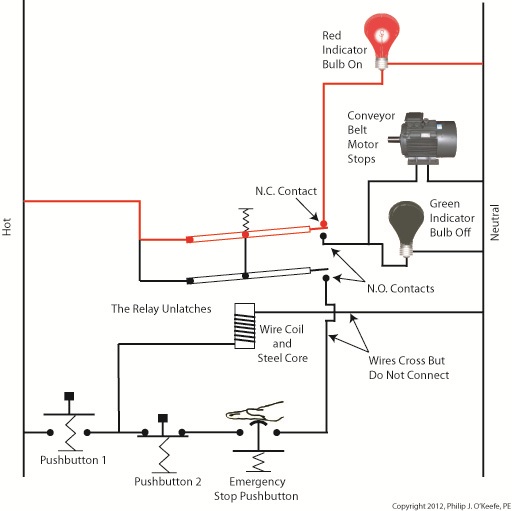

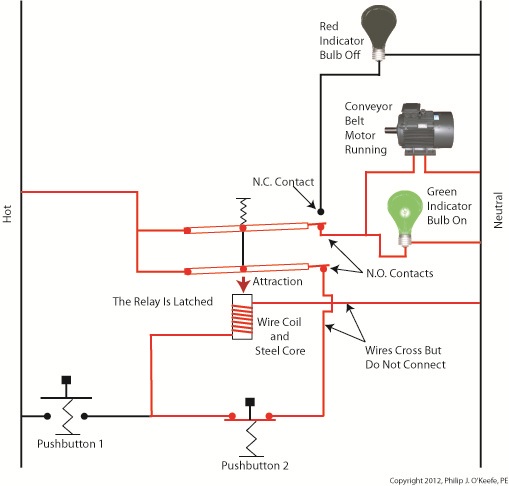

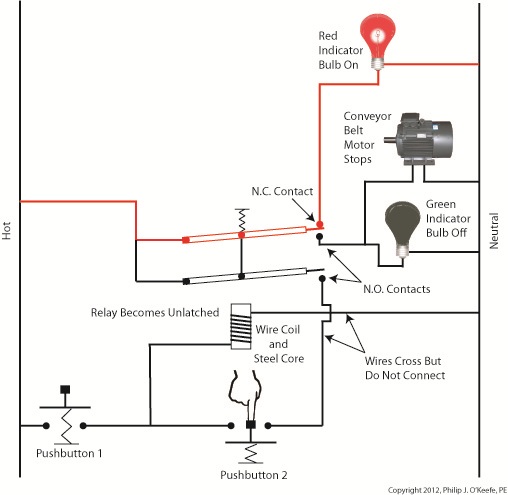

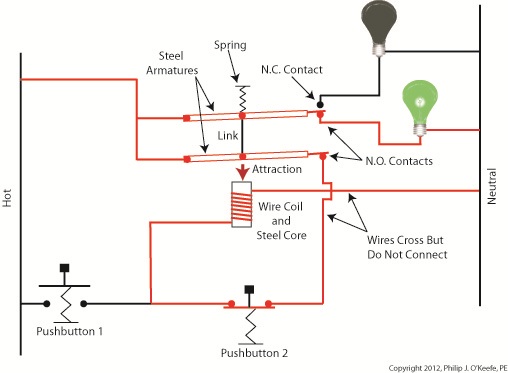

An emergency stop button has been incorporated into the circuit in Figure 2. It depicts what happens when someone depresses Button 1 on the conveyor control panel. The N.C. contact opens, and the two N.O. contacts close. The motor starts, and the lit green bulb indicates it is running. The electric relay is latched because its wire coil remains energized through one N.O. contact. It will only become unlatched when the flow of current is interrupted to the wire coil, as is outlined in the following paragraph. The red lines denote areas with current flowing through them. Both Button 2 and the emergency stop button typically reside in normally closed positions. As such electricity will flow through them on a continuous basis, so long as neither one of them is re-engaged. If either of them becomes engaged, the same outcome will result, an interruption in current on the line. The relay wire coil will then become de-energized and the N.O. contacts will stay open, preventing the wire coil from becoming energized again after Button 2 or the emergency stop are disengaged. Under these conditions the conveyor motor stops, the green indicator bulb goes dark, the N.C. contact closes, and the red light comes on, indicating that the motor is not running. This sequence, as it results from hitting the emergency stop button, is illustrated in Figure 3. Figure 3

We now have the means to manually control the conveyor from a convenient, at-the-site-of-occurrence location, which allows for a quick shut down of operations should the need arise. So what if something else happens, like the conveyor motor overheats and catches on fire and no one is around to notice and hit the emergency stop? Unfortunately, in our circuit as illustrated thus far the line will continue to operate and the motor will continue to run unless we incorporate an additional safeguard, the motor overload relay. We’ll see how that’s done next time. ____________________________________________ |

Posts Tagged ‘ladder diagram’

Industrial Control Basics – Emergency Stops

Sunday, February 26th, 2012Tags: control panel, control room, conveyor, de-energize equipment, electric relay, emergency pushbutton, emergency stop button, engineering expert witness, equipment shut down, fire, forensic engineer, hot, indicator bulb, industrial control, ladder diagram, latched relay, motor control, motor control circuit, motor overheat, N.C. contact, N.O. contact, NC contact, neutral, NO contact, overload relay, push button, pushbutton, relay armature, relay coil, relay ladder logic, safeguard, unlatched relay

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability, Professional Malpractice | 2 Comments »

Industrial Control Basics – Electric Motor Control

Sunday, February 19th, 2012| Electric motors are everywhere, from driving the conveyor belts, tools, and machines found in factories, to putting our household appliances in motion. The first electric motors appeared in the 1820s. They were little more than lab experiments and curiosities then, as their useful potential had not yet been discovered. The first commercially successful electric motors didn’t appear until the early 1870s, and they could be found driving industrial devices such as pumps, blowers, and conveyor belts.

In our last blog we learned how a latched electric relay was unlatched at the push of a button, using red and green light bulbs to illustrate the control circuit. Now let’s see in Figure 1 how that circuit can be modified to include the control of an electric motor that drives, say, a conveyor belt inside a factory. Figure 1

Again, red lines in the diagram indicate parts of the circuit where electrical current is flowing. The relay is in its normal state, as discussed in a previous article, so the N.O. contacts are open and the N.C. contact is closed. No electric current can flow through the conveyor motor in this state, so it isn’t operating. Our green indicator bulb also does not operate because it is part of this circuit. However current does flow through the red indicator bulb via the closed N.C. contact, causing the red bulb to light. The red and green bulbs are particularly useful as indicators of the action taking place in the electric relay circuit. They’re located in the conveyor control panel along with Buttons 1 and 2, and together they keep the conveyor belt operator informed as to what’s taking place on the line, such as, is the belt running or stopped? When the red bulb is lit the operator can tell at a glance that the conveyor is stopped. When the green bulb is lit the conveyor is running. So why not just take a look at the belt itself to see what’s happening? Sometimes that just isn’t possible. Control panels are often located in central control rooms within large factories, which makes it more efficient for operators to monitor and control all operating equipment from one place. When this is the case, the bulbs act as beacons of the activity taking place on the line. Now, let’s go to Figure 2 to see what happens when Button 1 is pushed. Figure 2

The relay’s wire coil becomes energized, causing the relay armatures to move. The N.C. contact opens and the N.O. contacts close, making the red indicator bulb go dark, the green indicator bulb to light, and the conveyor belt motor to start. With these conditions in place the conveyor belt starts up. Now, let’s look at Figure 3 to see what happens when we release Button 1. Figure 3

With Button 1 released the relay is said to be “latched” because current will continue to flow through the wire coil via one of the closed N.O. contacts. In this condition the red bulb remains unlit, the green bulb lit, and the conveyor motor continues to run without further human interaction. Now, let’s go to Figure 4 to see how we can stop the motor. Figure 4

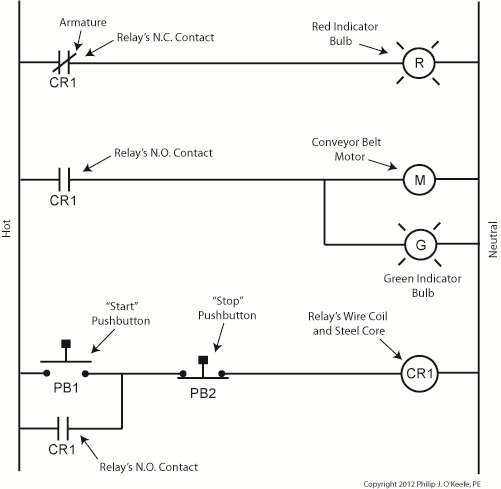

When Button 2 is depressed current flow through the relay coil interrupted. The relay is said to be unlatched and it returns to its normal state where both N.O. contacts are open. With these conditions in place the conveyor motor stops, and the green indicator bulb goes dark, while the N.C. contact closes and the red indicator bulb lights. Since the relay is unlatched and current no longer flows through its wire coil, the motor remains stopped even after releasing Button 2. At this point we have a return to the conditions first presented in Figure 1. The ladder diagram shown in Figure 5 represents this circuit. Figure 5

Next time we’ll introduce safety elements to our circuit by introducing emergency buttons and motor overload switches. ____________________________________________ |

Tags: blower, closed contact, control panel, control room, conveyor belt, electric current flow, electric motor, electric relay, engineering expert witness, equipment operator, factory, forensic engineer, indicator lamp, industrial control, ladder diagram, latched circuit, motor control, motor drive, N.C., N.O., normal state, normally closed, normally open, panel indicator, pump, push button, safety, start pushbutton, stop pushbutton

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability, Professional Malpractice | Comments Off on Industrial Control Basics – Electric Motor Control

Industrial Control Basics – Unlatching the Latching Circuit

Sunday, February 5th, 2012| When I had the misfortune of getting stuck in my Uncle Jake’s outhouse as a kid, I would allow my hysteria to get the best of me and forget my uncle’s instructions on how to get out. It was a series of raps and a single kick that would prove to be the magic formula, and once I had calmed myself down enough to employ them I would succeed in working the door’s rusty latch open. Our relay circuit below has a much less challenging system to effectively unlatch the pattern of electric current.

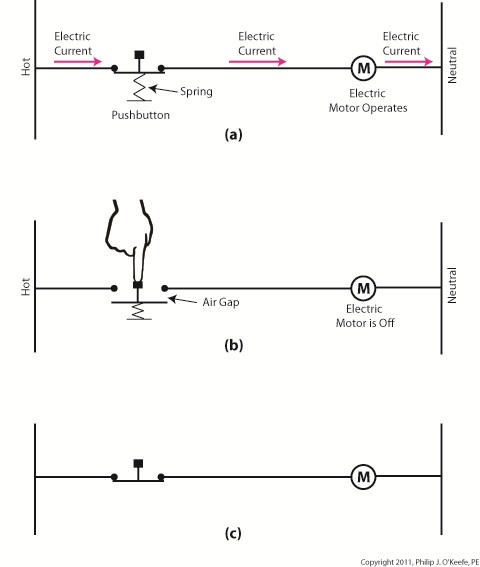

Figure 1 shows our latched circuit, where red lines denote the flow of current. Figure 1

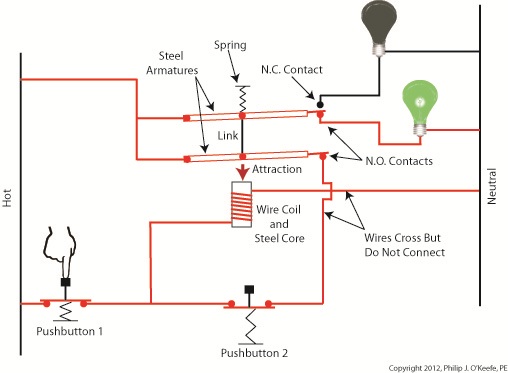

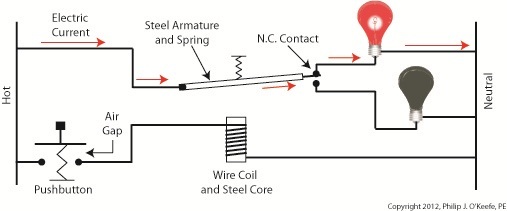

If you recall, the relay in this circuit was latched by pressing Pushbutton 1. When in the latched state, the magnetic attraction maintained by the wire coil and steel core won’t allow the relay armatures to release from their N.O. contacts. The relay’s wire coil stays energized via Button 2, the red bulb goes dark while the green bulb remains lit, even though Button 1 is no longer actively depressed. Now let’s take a look at Figure 2 to see how to get the circuit back to its unlatched state. Figure 2

With Button 2 depressed the flow of current is interrupted and the relay’s wire coil becomes de-energized. In this state the coil and steel core are no longer magnetized, causing them to release their grip on the steel armatures. The spring will now pull them back until one of them makes contact with the N.C. contact. The red bulb lights again, although Button 2 is not being actively depressed. At this point the electric relay has become unlatched. It can be re-latched by depressing Button 1 again. Let’s see how we can simplify Figure 2’s representation with a ladder diagram, as shown in Figure 3. Figure 3

We’ve seen how this latching circuit activates and deactivates bulbs. Next time we’ll see how it controls an electric motor and conveyor belt inside a factory. ____________________________________________ |

Tags: armature, bulbs, button, electric relay, electrical engineering, engineering expert witness, forensic engineer, hot neutral, industrial control, ladder diagram, latched relay, magnetism, mechanical relay, N.C. contact, N.O. contact, normally closed contact, normally open contact, pushbutton, pushbutton control, relay ladder logic, spring, unlatching a relay, wire, wire coil

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability, Professional Malpractice | Comments Off on Industrial Control Basics – Unlatching the Latching Circuit

Industrial Control Basics – Latching Circuit

Sunday, January 29th, 2012| When I think of latches the first thing that comes to mind is my Uncle Jake’s outhouse and how I got stuck in it as a kid. Its door was outfitted with a rusty old latch that had a nasty habit of locking up when someone entered, and it would take a tricky set of raps and bangs to loosen. One day it was being particularly unresponsive to my repeated attempts to open it, and the scene became like something out of a horror movie. There was a lot of screaming.

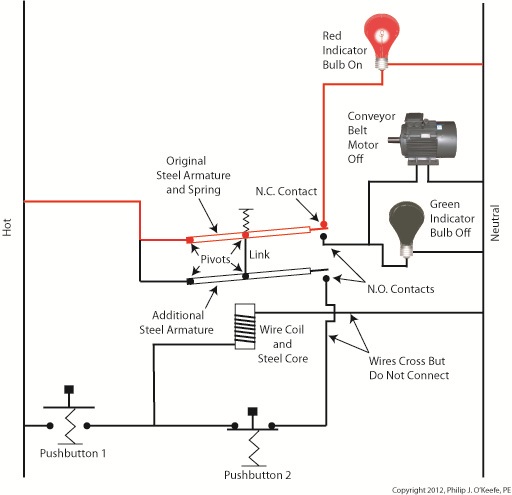

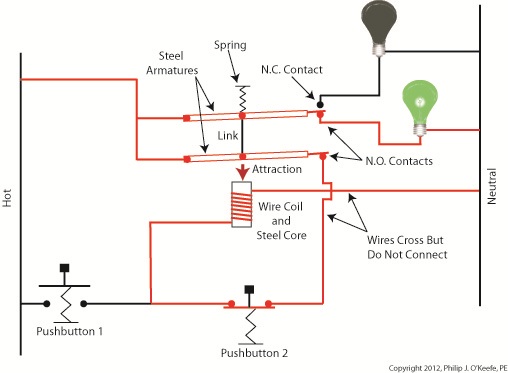

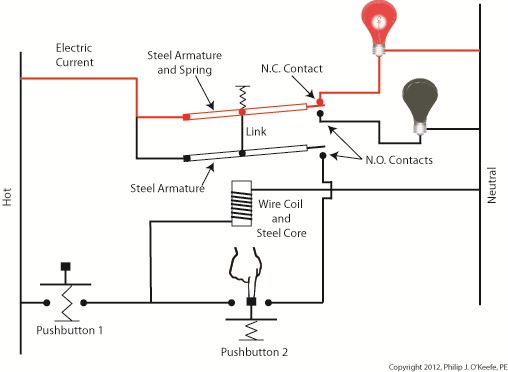

When latches operate well, they’re indispensable. Let’s take our example circuit from last time a bit further by adding more components and wires. We’ll see how a latch can be applied to take the place of pressure exerted by an index finger. See Figure 1. Figure 1

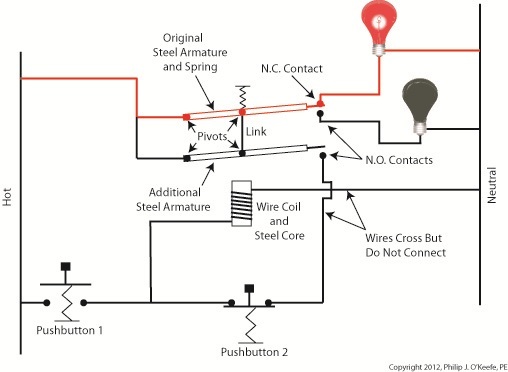

Our relay now contains an additional pivoting steel armature connected by a mechanical link to the original steel armature and spring. The relay still has one N.C. contact, but it now has two N.O. contacts. When the relay is in its normal state the spring holds both armatures away from the N.O. contacts so that no electric current will flow through them. One armature touches the N.C. contact, and this is the point at which current will flow between hot and neutral sides, lighting the red bulb. The parts of the circuit diagram with electric current flowing through them are denoted by red lines. Figure 1 reveals that there are now two pushbuttons instead of one. Now let’s go to Figure 2 to see what happens when someone presses on Button 1. Figure 2

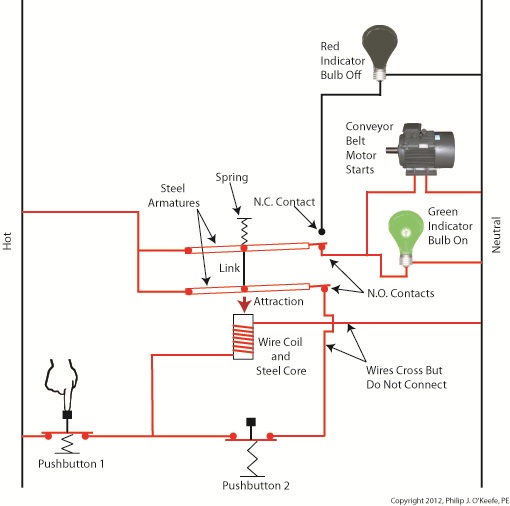

Again, the parts of the circuit diagram with current flowing through them are denoted by red lines. From this diagram you can see that when Button 1 is depressed, current flows through the wire coil, making it and its steel core magnetic. This electromagnet in turn attracts both steel armatures in our relay, causing them to pivot and touch their respective N.O. contacts. Electric current now flows between hot and neutral sides, lighting up the green bulb. Current no longer flows through the N.C. contact and the red bulb, making it go dark. If you look closely at Figure 2, you’ll notice that current can flow to the wire coil along two paths, either that of Button 1 or Button 2. It will also flow through both N.O. contact points, as well as the additional armature. So how is this scenario different from last week’s blog discussion? That becomes evident in Figure 3, when Button 1 is no longer depressed. Figure 3

In Figure 3 Button 1 is not depressed, and electric current does not flow through it. The red bulb remains dark, and the green bulb lit. How can this state exist without the human intervention of a finger depressing the button? Because although one path for current flow was broken by releasing Button 1, the other path through Button 2 remains intact, allowing current to continue to flow through the wire coil. This situation exists because Button 2’s path is “latched.” Latching results in the relay’s wire coil keeping itself energized by maintaining armature contact at the N.O. contact points, even after Button 1 is released. When in the latched state, the magnetic attraction maintained by the wire coil and steel core won’t allow the armature to release from the N.O. contacts. This keeps current flowing through the wire coil and on to the green bulb. Under these conditions the relay will remain latched. But, just like my Uncle’s outhouse door, the relay can be unlatched if you know the trick to it. Relays may be latched or unlatched, and next week we’ll see how Button 2 comes into play to create an unlatched condition in which the green bulb is dark and the red bulb lit. We’ll also see how it is all represented in a ladder diagram. ____________________________________________ |

Tags: armature, automatic controls, controls engineer, electric current, electric relay, electrical contacts, electromagnet, engineering expert witness, forensic engineer, hot, industrial control, ladder diagram, latched relay, N.C. contact, N.O. contact, NC contact, neutral, NO contact, normal state, normally closed, normally open, pushbutton, relay, relay ladder logic, unlatched relay, wire, wire coil

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability, Professional Malpractice | Comments Off on Industrial Control Basics – Latching Circuit

Industrial Control Basics – Electric Relay Ladder Diagram

Sunday, January 22nd, 2012| My daughter will be studying for her driver’s license exam soon, and I can already hear the questions starting. “What does that sign mean? Why does this sign mean construction is ahead?” Symbols are an important part of our everyday lives, and in order to pass her test she’s going to become familiar with dozens of them that line our highways.

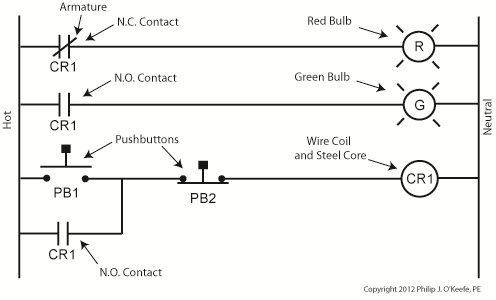

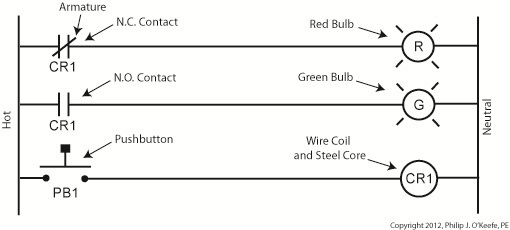

Just as a triangle on the highway is a symbol for “caution,” industrial control systems employ a variety of symbols in their diagrams. The pictures are shorthand for words. They simplify the message, just as hieroglyphics did for our early ancestors who had not yet mastered the ability to write. Ladder diagrams and the abstract symbols used in them are unique to industrial control systems, and they result in faster, clearer interpretations of how the system operates. Last week we analyzed an electric circuit to see what happens when we put a relay to use within a basic industrial control system, as found in Figure 1. Figure 1Now let’s see how it looks in an even simpler form, the three-rung ladder diagram shown in Figure 2. Figure 2In industrial control terminology the electric relays shown in ladder diagrams are often called “control relays,” denoted as CR. Since a ladder diagram can typically include many different control relays, they are numbered to avoid confusion. The relay shown in Figure 2 has been named “CR1.” Our ladder diagram contains a number of symbols. The symbol on the top rung which looks like two parallel vertical lines with a diagonal line bridging the gap between them represents the N.C. contact. This symbol’s vertical lines represent an air gap in the N.C. contact, the diagonal line is the relay armature which performs the function of bridging/closing the air gap. This rung of the ladder diagram represents the contact when the relay is in its normal state. In the middle ladder rung the N.O. contact symbol looks like two parallel vertical lines separated by a gap. There is no diagonal line running through it since the relay armature doesn’t touch the N.O. contact when this particular relay is in its normal state. The wire coil and steel core of this relay are represented by a circle on the bottom ladder rung. The contact and coil symbols on all three rungs are labeled “CR1” to make it clear that they are part of the same control relay. Other symbols within Figure 2 represent the red and green bulbs we have become familiar with from our initial illustration. They are depicted as circles, R for red and G for green, with symbolic light rays around them. The pushbutton, PB1, is represented as we have discussed in previous articles on ladder diagrams. Just as road sign symbols are faster than sentences for drivers speeding down a highway to interpret, ladder diagrams are faster than customary illustrations for busy workers to interpret. Next time we’ll expand on our electric relay by introducing latching components into the control system that will allow for a greater degree of automation. ____________________________________________ |

Tags: armature, automation engineer, bulb, contact, control relay, controls engineer, CR, electric relay, electrical contact, engineering expert witness, forensic engineer, hot, industrial automation, industrial control, ladder diagram, ladder diagram symbol, ladder logic, N.C. contact, N.O. contact, NC contact, neutral, NO contact, normal state, normally closed, normally open, pushbutton, relay, rung, steel core, wire coil

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability, Professional Malpractice | 2 Comments »

Industrial Control Basics – Pushbuttons

Monday, December 26th, 2011Tags: control system, current flow, electric motor, electrical circuit, engineering expert witness, forensic engineer, hot, industrial control, ladder diagram, machine control, mechanized equipment, motor control, neutral, normally closed, normally open, pushbutton, relay, spring, switch

Posted in Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability, Professional Malpractice | Comments Off on Industrial Control Basics – Pushbuttons

Industrial Control Basics – Ladder Diagrams

Sunday, December 18th, 2011| The other day I pressed the button to activate my electric garage door opener and nothing happened. I pushed again and again, still nothing. Finally, I convinced myself to get out of the car and take a closer look. A wooden board I had propped up against the side of the garage wall had come loose, wedging itself in front of the electric eye, you know, the one that acts as a safety. The board was an obstruction to the clear vision of the eye. It couldn’t see the light emitter on the other side of the door opening and wouldn’t permit the door opener to function.

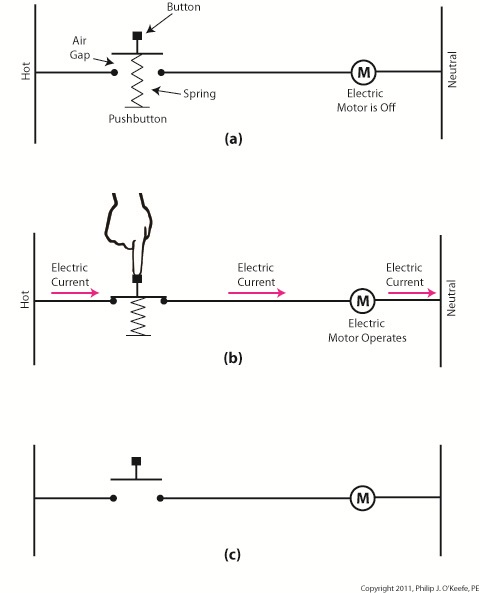

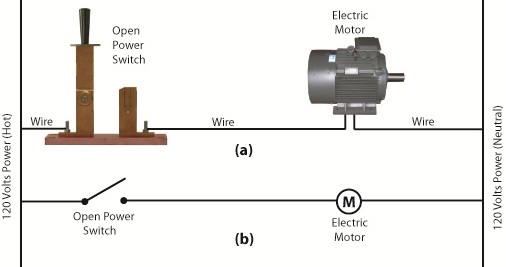

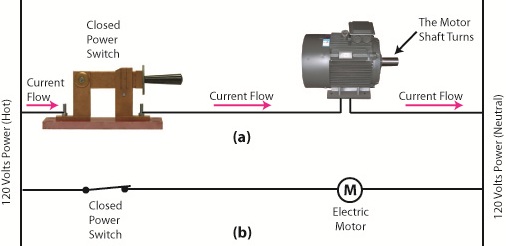

The basic manual control system we looked at last week operates similarly to the eye on a garage door opener. If you can’t “close the loop,” you won’t get the power. Last week’s example was as basic as things get. Now let’s look at something a bit more complex. Words aren’t always the best vehicle to facilitate understanding, which is why I often use visual aids in my work. In the field of industrial control systems diagrams are often used to illustrate things. Whether it’s by putting pencil to paper or the flow diagram of software logic, illustrations make things easier to interpret. Diagrams such as the one in Figure l are often referred to as “ladder diagrams,” and in a minute we’ll see why. Figure 1 Figure 1(a) shows a basic manual control system. It consists of wires that connect a power switch and electric motor to a 120 volt alternating current power source. One wire is “hot,” the other “neutral.” The hot side is ungrounded, meaning that it isn’t electrically connected to the Earth. The neutral side is grounded, that’s right, it’s driven into the ground and its energy is dissipated right into the earth, then returned back to the power grid. In Figure 1(a) we see that the power switch is open and an air gap exists. When gaps exist, we don’t have a closed electrical loop, and electricity will not flow. Figure 1(b), our ladder diagram, aka line diagram, shows an easier, more simplified representation of the manual control shown in Figure 1(a). It’s easier to decipher because there’s less going on visually for the brain to interpret. Everything has been reduced to simple lines and symbols. For example, the electric motor is represented by a symbol consisting of a circle with an “M” in it. Now, let’s turn our attention to Figure 2 below to see what happens when the power switch is closed. Figure 2 The power switch in Figure 2(a) is closed, allowing electric current to flow between hot and neutral wires, then power switch, and finally to the motor. The current flow makes the motor come to life and the motor shaft begins to turn. The line diagram for this circuit is shown in Figure 2(b). You might have noticed that the line diagrams show in Figures 1(b) and 2(b) have a rather peculiar shape. The vertically running lines at either side depict the hot and neutral legs of the system. If you stretch your imagination a bit, they look like the legs of a ladder. Between them run the wires, power switch, and motor, and this horizontal running line represents the rung of the ladder. More complicated line diagrams can have hundreds, or even thousands of rungs, making up one humongous ladder, hence they are commonly referred to as ladder diagrams. Next week we’ll take a look at two key elements in automatic control systems, the push button and electric relay, elements which allow us to do away with the need for human intervention. ____________________________________________ |

Tags: automatic control, electric circuit, electric current, electric motor, electric relay, electric utility, engineering expert witenss, forensic engineer, ground, hot, industrial control, ladder diagram, ladder logic, line diagram, manual control, motor control, neutral, power flow, power grid, power switch, push button, visual aid, wires

Posted in Courtroom Visual Aids, Engineering and Science, Expert Witness, Forensic Engineering, Innovation and Intellectual Property, Personal Injury, Product Liability, Professional Malpractice | Comments Off on Industrial Control Basics – Ladder Diagrams