| The other day I pressed the button to activate my electric garage door opener and nothing happened. I pushed again and again, still nothing. Finally, I convinced myself to get out of the car and take a closer look. A wooden board I had propped up against the side of the garage wall had come loose, wedging itself in front of the electric eye, you know, the one that acts as a safety. The board was an obstruction to the clear vision of the eye. It couldn’t see the light emitter on the other side of the door opening and wouldn’t permit the door opener to function.

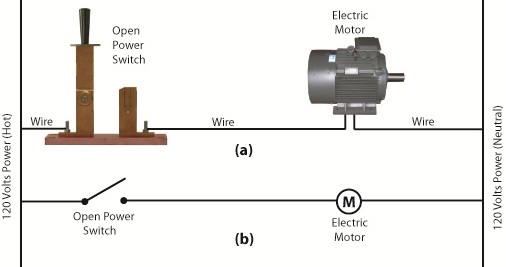

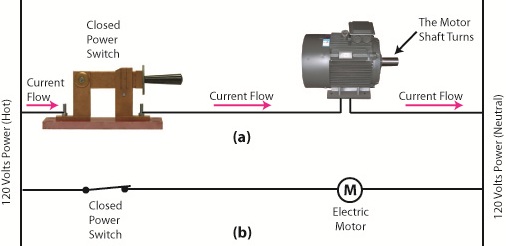

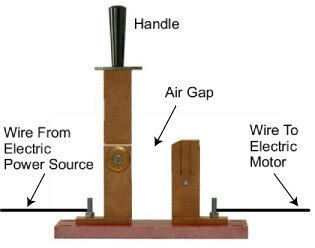

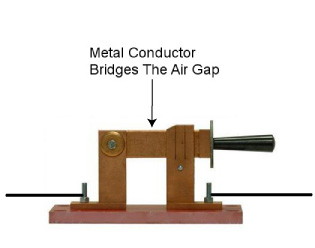

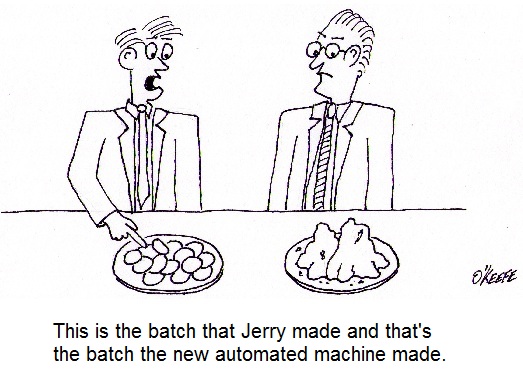

The basic manual control system we looked at last week operates similarly to the eye on a garage door opener. If you can’t “close the loop,” you won’t get the power. Last week’s example was as basic as things get. Now let’s look at something a bit more complex. Words aren’t always the best vehicle to facilitate understanding, which is why I often use visual aids in my work. In the field of industrial control systems diagrams are often used to illustrate things. Whether it’s by putting pencil to paper or the flow diagram of software logic, illustrations make things easier to interpret. Diagrams such as the one in Figure l are often referred to as “ladder diagrams,” and in a minute we’ll see why. Figure 1 Figure 1(a) shows a basic manual control system. It consists of wires that connect a power switch and electric motor to a 120 volt alternating current power source. One wire is “hot,” the other “neutral.” The hot side is ungrounded, meaning that it isn’t electrically connected to the Earth. The neutral side is grounded, that’s right, it’s driven into the ground and its energy is dissipated right into the earth, then returned back to the power grid. In Figure 1(a) we see that the power switch is open and an air gap exists. When gaps exist, we don’t have a closed electrical loop, and electricity will not flow. Figure 1(b), our ladder diagram, aka line diagram, shows an easier, more simplified representation of the manual control shown in Figure 1(a). It’s easier to decipher because there’s less going on visually for the brain to interpret. Everything has been reduced to simple lines and symbols. For example, the electric motor is represented by a symbol consisting of a circle with an “M” in it. Now, let’s turn our attention to Figure 2 below to see what happens when the power switch is closed. Figure 2 The power switch in Figure 2(a) is closed, allowing electric current to flow between hot and neutral wires, then power switch, and finally to the motor. The current flow makes the motor come to life and the motor shaft begins to turn. The line diagram for this circuit is shown in Figure 2(b). You might have noticed that the line diagrams show in Figures 1(b) and 2(b) have a rather peculiar shape. The vertically running lines at either side depict the hot and neutral legs of the system. If you stretch your imagination a bit, they look like the legs of a ladder. Between them run the wires, power switch, and motor, and this horizontal running line represents the rung of the ladder. More complicated line diagrams can have hundreds, or even thousands of rungs, making up one humongous ladder, hence they are commonly referred to as ladder diagrams. Next week we’ll take a look at two key elements in automatic control systems, the push button and electric relay, elements which allow us to do away with the need for human intervention. ____________________________________________ |

Archive for the ‘Professional Malpractice’ Category

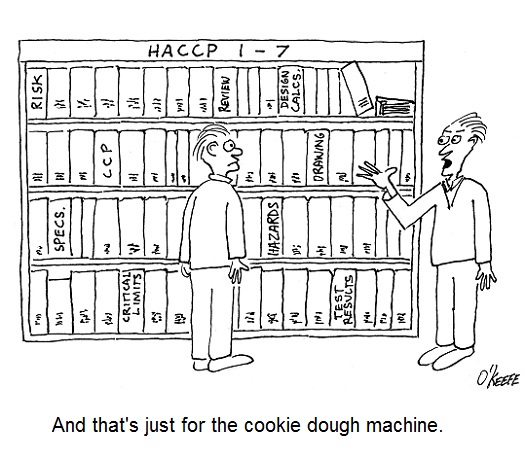

Food Manufacturing Challenges – HACCP Design Principle No. 6

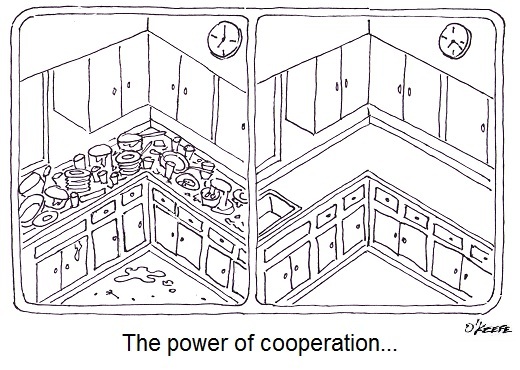

Sunday, November 20th, 2011| My daughter’s boy friend stayed for dinner recently and was impressed with our after-dinner cleanup. He watched as each of us carried out our individual assigned tasks, my wife putting away leftovers and condiments, my daughter rinsing and stacking plates into the dishwasher, and me at the sink hand washing. To him we seemed a model of efficiency. It didn’t take long to return the kitchen to its usual state of pristine evening cleanliness. “Our kitchen is always a mess,” he complained, “probably because we’re so disorganized.”

You can imagine what would happen if a food manufacturing plant operated like a disorganized household kitchen. Although employees may know they are responsible for delivering safe products to consumers, without the right procedures in place an unsafe chaotic mess may result. To get everyone moving in the right direction we look to guidelines established in HACCP Design Principle No. 6. Principle 6: Establish procedures for ensuring the HACCP system is working as intended. – In large part this Principle acts as a report card. It follows up on the guidelines established in Principles l through 5, organizing activities into written procedures. For example, design engineers must routinely analyze important identified stages within a design project, then write procedures, that is, a step-by-step instruction guide, which encompasses them. In this way personnel involved in the design process make best use of the safeguards put in place by HACCP Design Principles 1 through 5. These steps include things like preparing design proposals, analyzing risks and hazards, creating preliminary designs, conducting design reviews, building prototype equipment and tooling, running tests, collecting test data, and analyzing test results. For each step, responsibilities of key individuals involved must be clearly defined and sequentially ordered. But writing department procedures is only part of Principle 6. Procedures are no good if they’re just thrown into a file cabinet and no one ever looks at them. What good are guidelines without a full understanding of how to use them? Training may be necessary, and management must decide what form that educational process takes to be most effective. Engineering management must verify that established procedures are adequate to the task. This typically involves taking a hard look at finished design projects and checking critical factors. Was an adequate risk analysis performed? Were sufficient critical control points established and critical limits monitored for effectiveness? Next time we’ll wrap up our discussion on HACCP Design Principles by examining No. 7. It’s the last of the Principles and it’s concerned with establishing record keeping procedures. ____________________________________________

|

Food Manufacturing Challenges – HACCP Design Principle No. 5

Saturday, November 12th, 2011| Picture yourself on a highway, it’s dark out, the wind is blowing fiercely, and you’re unable to see that the pavement is accumulating icy patches. You hit one, and your car veers out of control. Luckily you drive one of the new generation of “smart” vehicles. Wheel sensors detect your predicament and immediately initiate a sequence of events to correct the situation and bring your vehicle back into control.

Corrective measures need to be taken in many situations when things go awry, whether they be computer-generated or human-generated corrections, and food manufacturing facilities are not exempt from the process. Let’s look at how this applies within HACCP Design Principle No. 5. Principle 5: Establish corrective actions. – Simply put, when an established critical limit at a designated critical control point (CCP) has been found not to be functioning as intended, thereby exposing consumers to potential food safety issues, design engineers must enact corrective measures to resolve the issue as soon as possible. Let’s return to the example set out in our last article, where we discussed HACCP Design Principle 4. An engineering manager has discovered a problem with the lower critical limits established by her design engineer’s software logic as it concerns a CCP established with regard to cooker temperature. The time and temperature in the logic create a hazardous situation by not taking into account that larger cuts of meat require more cooking time, resulting in them being undercooked. Fortunately, the engineering manager’s diligent and ongoing day-to-day monitoring has alerted her to the error. She immediately provides feedback about it to the design engineer, who makes corrections to the software logic. Problem solved, and all is working well within the food manufacturing plant, right? Yes, but we’re not finished. We have to make sure that a mechanism is set in place to ensure that HACCP Principles 1 through 5 are being followed and that they are actually working to protect consumers from potential food contamination hazards. Next time we’ll take a look at the last of the HACCP Design Principles, No. 6, which concerns itself with maintenance and housekeeping issues. ____________________________________________ |

Food Manufacturing Challenges – HACCP Design Principle No. 3

Sunday, October 30th, 2011| How do parents make life safer and healthier for their kids? One of the ways is to impose limits on things like roaming distance within the neighborhood, curfews, and insisting that you eat your vegetables. Just common sense, right? Let’s take a look at some more of it.

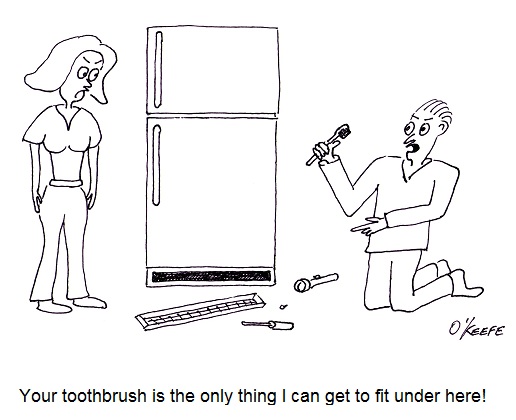

Limits are also necessary within the food manufacturing industry. Let’s take a look at Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) Principle No. 3 to see how they’re established and why. Principle 3: Establish critical limits for each critical control point. – You can think of a critical limit as a boundary of safety for each critical control point (CCP). So how do you determine that boundary of safety? It’s difficult to generalize, but if you’ve ever watched the TV show Hoarders, you have an excellent example of one that has not only been breeched, but torn asunder. In order to prevent things in the commercial food industry from getting anywhere near Hoarders bad, maximum and minimum values are set in place, representing safeguards to physical, biological, and chemical parameters at play within the industry. Critical limits can be obtained from regulatory standards and guidelines, scientific literature, experimental studies, as well as information provided by consultants. These critical limits come into play with issues as varied as machine design, raw material temperatures, and overall safe processing times. How could the hoarders let things get so bad? If you listen carefully, you’ll hear bits of information that provide a clue. They’ll say it started with a few things falling to the floor which they didn’t feel like picking up and it escalated from there. Now all of us live within environments which differ as to their cleanliness, but by and large we live within space where we feel comfortable and consider to be reasonably clean. We don’t all habitually move stoves and refrigerators to clean, for example. But if we were so inclined, refrigerators do come with front access panels that are easily removed. Trouble is the space they provide access to often isn’t large enough to accommodate hands and a vacuum cleaner nozzle comfortably. You can imagine how frustrating and potentially dangerous it would be to public health to have commercial machinery that provided such limited access for cleaning. To cope with this problem design engineers institute minimum and maximum parameters, such as in the critical limit dimensions of a removable cover. Their guideline would ensure that enough space is provided so that personnel can fully access all aspects of machinery with tools for cleaning. That same cover can also have established maximum critical limits, so that dimensions aren’t too large and heavy to be manipulated by hand. Human nature being what it is, something that is too difficult to remove may be “forgotten” and parts of the machine may never get cleaned. Raw meats and many produce can contain hazards like salmonella, E. coli, and other nasty critters that are dangerous to human health. One of the ways the commercial food industry works to ensure that these contaminants aren’t unleashed on the public is to install programmable control systems into processing machinery that essentially cooks the meat at an established minimum temperature for a minimum amount of time. Utilizing this type of temperature control in conjunction with an established maximum cooking parameter for temperature and time will virtually eliminate the possibility of overcooked or burnt food products. When you buy that frozen dinner in most cases it’s completely cooked, but it’s a rarity to find it’s been burned. Another situation in which critical limits are utilized is in the maintenance of machinery, such as when they limit the number of hours a machine can be operated before it is shut down for servicing. Next week we’ll move on to Principle No. 4 and see how it establishes monitoring requirements for each CCP. ____________________________________________ |

Food Manufacturing Challenges – HACCP Design Principle No. 2

Sunday, October 23rd, 2011| What would you do if you heard an unfamiliar sound coming from your water heater? If you’re like most people you’d make a mental note to keep an eye on it, but ignore it for the most part. Unfortunately, this less than proactive approach often results in water heater floods. As an engineer, I’m more likely than the general population to investigate the cause of the water heater’s sound and proactively seek a remedy before a real problem has a chance to develop.

The FDA’s Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) seeks to accomplish the same with regard to food production. As discussed last week with regard to HACCP Principle 1, those involved in designing food processing equipment must proactively analyze designs to identify potential food safety hazards. Now let’s see how common sense is once again employed through Principle 2, guiding design engineers to take control of situations where hazards have been identified through Principle 1. HACCP Principle 2: Identify critical control points. A critical control point (CCP) is a step in the design process at which a control can be most effectively introduced to prevent or eliminate hazards. In this context a “control” would be a design revision to eliminate hazards identified during the Principle 1 stage. We will once again use the two examples introduced in last week’s blog discussion on Principle 1. In our first example, hazard analysis revealed that food can accumulate in a food processing machine in areas where cleaning is difficult or impossible. This accumulation would eventually rot and fall into uncontaminated food passing through production lines. Design engineers would work to address this contamination hazard by identifying a CCP within the design process, that is, the best place where a preventative measure can be added to the machine setup to facilitate removal of the accumulation. At that CCP, measures can be taken to change the machine’s design. Perhaps all that is needed to correct the situation is to include easy to remove access covers. In our second example hazard analysis revealed that the metal tooling as designed for our food production machine was too fragile and would not withstand the repeated forces imposed on it by the mass production process. This design flaw presents a strong possibility that metal parts will break off and enter food on the line. To correct this situation, design engineers must once again identify the juncture within the design process at which a CCP is identified. There, a preventative measure can most effectively be introduced, enabling more robust metal to be used in the tooling. The previous two examples illustrate CCPs being utilized within the design process. CCPs can also be introduced outside the design process, as when they are identified during the course of training procedures involving the operation, cleaning, and general maintenance of equipment and production lines. And an excellent way of implementing this approach is to have design engineers collaborate with operating and maintenance staff. Working together, they are best able to identify key elements to be addressed and make note of them within written procedures. Now that we have identified some examples of CCPs within the design process, we can move on to HACCP Principle 3 and how it guides design engineers to establish critical limits for each CCP.

|

Food Manufacturing Challenges – Avoiding Contamination

Sunday, October 9th, 2011| Perhaps you’ve heard of the non-reciprocal wine and sewage principle. I’m not sure where it originated, but it states that if you add a cup of wine to a barrel of sewage, you still get a barrel of sewage. No brainer, right? Well, consider the flip side. If you add a cup of sewage to a barrel of wine, you also get nothing more than a barrel of sewage. In other words, a small amount of contamination goes a long way.

The premise of this principle also applies within the food manufacturing industry. If you were to add uncontaminated food to garbage, you would just get more garbage, and if you add garbage to food… well, you get it. The term garbage can encompass an endless variety of contaminants, such as broken glass, metal shavings, nuts, bolts, plastic fibers, grease, broken machine parts, errant human body parts, and on and on. Although the FDA does allow for certain levels of natural contaminants, like insect parts and rodent hairs, consumers are never pleased when undesirable elements enter their food supply. It could even be dangerous. When design engineers create food processing machinery and production lines, they must be on the lookout for potential risks of contamination hazards. They must also provide a quick means of mitigation, before contaminants can enter into commercial production. A systematic approach provides the best means of addressing these needs, allowing for a pre-emptive method to ensure food safety. Checklists and procedural policy set in place for these reasons will enable design engineers to identify, assess, and control risks before they turn into hazards. This is where Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) planning comes in. To address these needs, the FDA has set up the HACCP (pronounced, “hass-up”) system, defined as “…a management system in which food safety is addressed through the analysis and control of biological, chemical, and physical hazards from raw material production, procurement and handling, to manufacturing, distribution and consumption of the finished product.” HACCP is the outgrowth of FDA current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP), which are set out in the Code of Federal Regulations pertaining to commercial food processors and manufacturers, Title 21, Part 110, entitled, “current Good Manufacturing Practice in Manufacturing, Packing or Holding Human Food.” Every commercial food processor, regardless of size, must implement a cGMP/HACCP quality assurance program to comply with these regulations. HACCP is a proactive strategy where hazards are identified, assessed, and then control measures developed to prevent, reduce, or eliminate potential hazards. A key element of HACCP involves prevention of food contamination during all phases of manufacturing, and way before the finished food product undergoes quality inspection. This strategy extends into the food manufacturing equipment and production line design process as well. Next time we’ll continue our look at HACCP and how its seven principles are used by design engineers to prevent food product contamination. |

Industrial Ventilation

Sunday, March 27th, 2011| On a hot, sticky day, what price would you pay for a cool breeze? Imagine for a moment that it’s 90 degrees in the shade and humidity is 85%. There are few human beings that wouldn’t consider this uncomfortable weather, although I have some die hard neighbors who rarely close their windows during the summer to engage the air conditioning, a rather recent modern convenience. My mom told me stories of how it was common in the 1940s for entire Chicago neighborhoods to head to Lake Michigan, spread a blanket, and sleep on the beach to keep cool on the hottest nights. As for myself, I remember being really happy when Dad broke down and finally purchased a window air unit. It was as big as a small refrigerator and took two men to lift. It was loud and drew so much power it frequently “blew the fuse.” It was so much nicer when central air conditioning came along a few years later and we could finally retire that old clunker.

Ultimately, it’s ventilation that makes air conditioning work, the principle here being a continuous circulation of air, exchanging hot for cooled. If you’ll remember, hot air gives up its heat to coils containing coolant, and the newly cooled air is released back into the room. In addition to cooling, another major function of ventilation is to remove odors and refresh the air. Everyone likes a fresh smelling home, but even more importantly, proper ventilation reduces the concentration of contaminants in the air, things which tend to make us sick, like mold. That’s why many states’ building codes require whole house air ventilation systems to be installed in new homes. In industrial settings ventilation performs the same functions, but it’s necessary for other reasons as well. Industrial facilities often house processes that create airborne toxins and other contaminants. These byproducts of manufacturing can be dangerous if allowed to collect unchecked within the confines of a building. Air containing certain concentrations of contaminants, such as vapors emitted by paints and solvents, can ignite, resulting in fire or explosion. For safety of both workers and equipment, fresh air must displace air contaminated with fumes and dust. There are three types of ventilation that can be found in industrial facilities. These include indoor air quality ventilation, dilution ventilation, and local exhaust ventilation. Indoor air quality ventilation provides freshly heated or cooled air to buildings as part of the normal heating, ventilating and air conditioning system, much like we have in our own homes. Dilution ventilation gets its name from the fact that it dilutes contaminated air by displacement, the blowing in of clean air and exhausting of dirty. The last type of ventilation, local exhaust ventilation, captures contaminated emissions at or near the source and exhausts them directly outside. Depending on the type of industrial application one, two, or all three of these ventilation types may be employed to keep air quality safe. Next week we’ll discuss dilution ventilation in detail, followed by local exhaust ventilation, and we’ll gain a better understanding of how they are used to protect worker health and safeguard property. _____________________________________________ |